After a meal of questionable seafood or a few sips of contaminated water, bad bacteria can send your digestive tract into overdrive. Your intestines spasm and contract, efficiently expelling everything in the gut — poop and bacteria alike.

A new study from the University of Oregon shows how one kind of bacteria, Vibrio cholerae, triggers those painful contractions by activating the immune system. The research also finds a more general explanation for how the gut rids itself of unwanted intruders, which could also help scientists better understand chronic conditions like inflammatory bowel disease.

“This isn’t a specific nefarious activity of the Vibrio bacteria,” said Karen Guillemin, a microbiologist at the UO who collaborated on the work with biophysicist Raghu Parthasarathy. “The gut is a system where the default is, when there’s damage, you flush.”

The research was led by Julia Ngo, a now-graduated doctoral student in Guillemin and Parthasarathy’s labs, and published Nov. 22 in the journal mBio.

Vibrio cholerae is best known for causing cholera, a severe illness that infects millions of people per year, often via contaminated water. A related Vibrio species is frequently linked to food poisoning from shellfish.

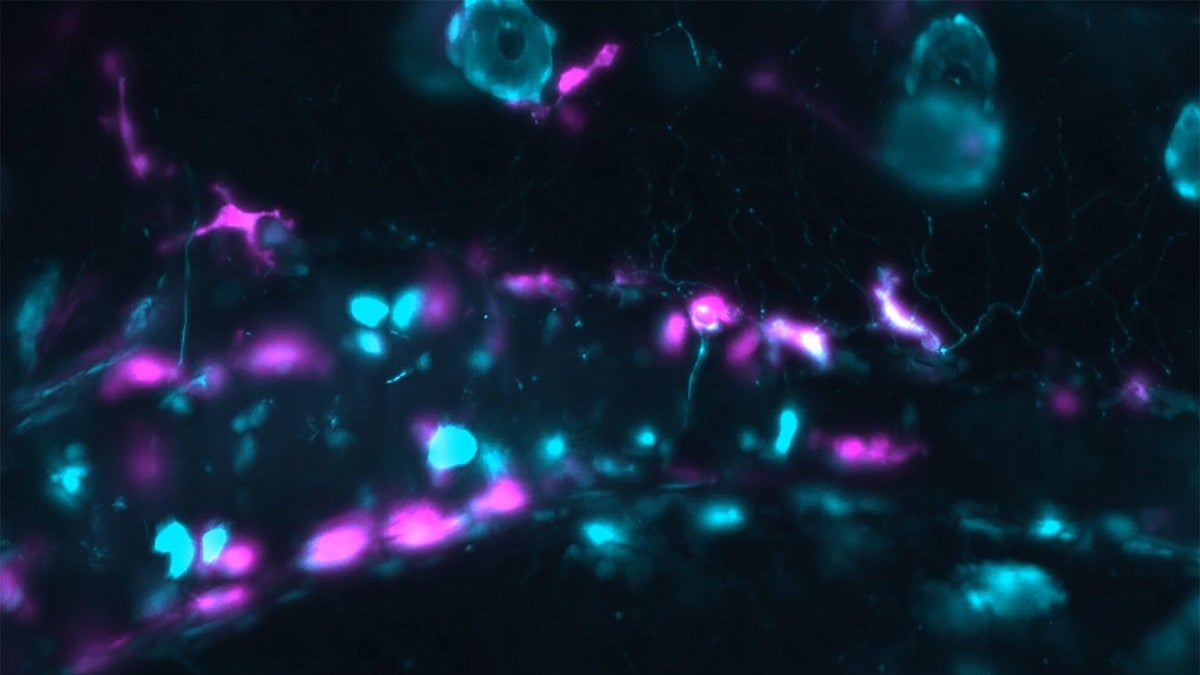

In past work, Parthasarathy’s lab has shown that Vibrio cholerae bacteria amped up the strength of gut contractions in zebrafish. These fish, which are transparent as larvae, are a powerful tool for studying the dynamics of microbes in the gut because scientists can visualize what’s happening in real time.

The team pinned the effect on a sword-like surface appendage that Vibrio bacteria usually use as a weapon against other microbes. Disarming the bacteria calmed the gut contractions — but they weren’t sure how or why.

Normally, macrophages tamp down the activity of neurons in the gut, keeping them calm and allowing things to move through the gut at a normal speed. But in response to tissue damage from the bacteria, the macrophages leave their posts and flock to the site of calamity, leaving the neurons unattended. Without macrophages to keep things in check, the neurons end up in overdrive, triggering strong contractions.

“It’s amazing how dynamic all these cells are, the macrophages racing across the fish, the neurons and muscles pulsing with activity,” Parthasarathy notes. “Without the ability to observe these phenomena in live animals, tracking cells and measuring gut contractions, we wouldn’t have figured any of this out.”

“If the macrophages have to go deal with an injury, then it actually makes a lot of sense for the neurons to freak out and just push everything out of the gut,” Guillemin said. “If there's something in the gut that's causing injury, you want to get it out of there.”

The gut flushing is probably beneficial for the bacteria, too, giving them speedy access to new hosts. But Guillemin cautions against giving too much agency to microbes. The fact that Vibrio’s weaponry against other bacteria also triggers this strong intestinal response probably isn’t an exquisite adaptation, she said, but rather a convenient coincidence.

The study also highlights how cross talk between the immune and nervous systems might play an underappreciated role in gut health, Parthasarathy suggested. Deciphering how microbes influence that cross talk might give scientists new insights into a range of puzzling diseases.

The work was supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health.

—By Laurel Hamers, University Communications

—Top photo: Gut cells, highlighted in magenta, in a zebrafish. The blue cells show where the immune system is stimulated. (Photo courtesy of the Parthasarathy and Guillemin labs)