Gathered together, they’d be your typical group of students: bike-riding, burrito-eating, PNW-loving University of Oregon undergrads. Dig into conversation with them, however, and you’ll discover they’re far from ordinary.

More undergraduates than ever before are presenting innovative, surprising research at this year’s Undergraduate Research Symposium on May 16 in the Erb Memorial Union — more, as in 513 student presenters with nearly 300 faculty mentors supporting their work along the way.

“These students are incredibly impressive, yet humble,” said Josh Snodgrass, associate vice provost for undergraduate research and distinguished scholarships, and co-chair of the symposium. “Not only is the research they’re doing impressive, but so often it also reflects their deep commitment to making the world a better place through scientific discovery, social justice or artistic performance.”

So, what kind of surprising, extraordinary research are we talking about here? Research translating dance into poetry, digging into how interruption in the development of the nervous system that controls the gastrointestinal system can permanently change its function, and the sociosexual behavior of bonobos, one of the species of primates closest to humans, and how that behavior is affected by stress for starters. Here are some of 2019’s undergraduate research standouts.

Adie Fecker

Right brain, left brain. Hard science versus the humanities. For Adie Fecker, the answer is yes, all of the above.

A Clark Honors College student and biology major, Fecker’s passion for making change manifests through her commitment to ecopoetry cultivated through a relationship with Barbara Mossberg in the honors college and mentorship from Oregon Poet Laureate Kim Stafford. Fecker describes her work as responding to environmental destruction through creativity and creation.

Her passion also shows up in research she’s conducting under the supervision of biology professor Philip Washbourne related to identifying parts of the forebrain that may affect social behavior for those on the autism spectrum.

She is presenting on both of her research endeavors at this year’s symposium. When asked to pick between her research projects, she chose her lab work because she’s dedicated more time to it, but she was quick to point out that there’s no need to choose.

“I think I’ve always been someone who likes interdisciplinary focuses, and for me my poetry has always been a far more personal thing, versus my biological interests, which have been more of an external pursuit,” Fecker said. “But I think they’re very much the same. The same way of thinking, the same way of how do we build something from these random pieces of information. I think they have a lot more in common than people think.”

Mat Wilson

No stranger to a diverse set of interests, Mat Wilson will admit he was a bit of a stranger to university life when he arrived at the UO.

A first-generation transfer student and anthropology major, Wilson dove into research with a modicum of misconceptions.

“Initially, when I came to college I thought that research was this thing that happened back in a lab somewhere, no windows, hidden away; it was very much a STEM thing,” Wilson said. “Being on this campus and seeing what research looks like … and being able to reconceptualize research as something that everyone does all the time, and that it’s a skill that anybody can do, has been transformative.”

Wilson — who spent countless hours in Frances White’s laboratory remotely observing a population of bonobos, a species of primate often mistakenly referred to as pygmy chimpanzees — is unsure of how his research will evolve. He is certain, however, of the value of the faculty and graduate student connections he’s made through research and how they’ve enriched his time at the UO.

In addition to his bonobos research project, Wilson, a McNair Scholar and a peer advisor in the Office of Academic Advising, also conducted applied research on use of EMU facilities as an intern in the student life Emerging Leaders Program working with EMU director Laurie Woodward.

Kendra Siebert

Connection, between people, the art they create and how those creations affect social movements, is a topic being tackled by advertising and journalism major Kendra Siebert.

Siebert, who is minoring in Spanish, spent summers with local artists renowned for urban art throughout the Mexican state of Oaxaca, particularly Mexico City. Through extensive personal interviews with the artists, often surrounded by the art they created, Siebert found confidence she didn’t know she had and honed skills she’ll use throughout the rest of her life.

“I didn’t know a lot about myself and the way I am, and the way I interact with people,” Siebert said. “I guess I would say that throughout this process I’ve really learned so much more about my ability to connect with people.”

A self-proclaimed “city person” from Portland, Siebert said she expects to revisit Mexico City in the future and that the friendships she’s developed with some of the artists she met through her research will continue for the rest of her life.

“Research has definitely opened me up to a lot of things that traditional classes just don’t,” she said.

Christine Pons

A lack of interest in laboratory research work made human physiology seem like an odd choice of a major for 21-year-old Christine Pons, at least on the surface.

Pons is conducting research outside the lab, under the guidance of professor Liz Budd and the Prevention Science Institute, on the implementation of Oregon wellness policies at schools throughout the state.

More specifically, she’s looking at ways to encourage healthy activity for children during the school day when sometimes it seems the only answer to disciplinary challenges is for teachers to take away recess or physical education time. She is also looking at how the local community “influences the services provided for student’s nutritional and physical health and attempts to prevent obesity.”

“(This project) gave me an opportunity to look more into my community and see how I could help them through research,” Pons said. “It allowed me to fill areas of knowledge that weren’t there yet, so I could contribute to a better and healthier community.”

Pons, herself a sports lover, said that much like team sports, research takes a village. She expressed deep appreciation for the mentors, thesis committee members and community liaisons who made her research project, and hundreds of others, possible.

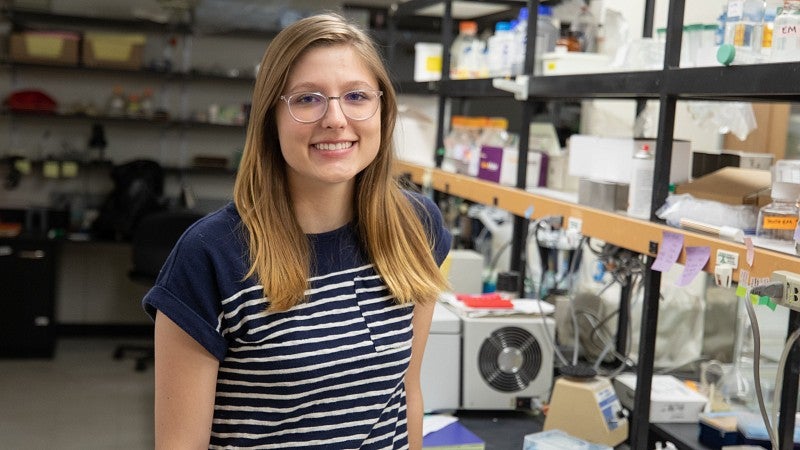

Lilly Carroll

Going with her gut meant a change in future aspirations for biology major Lilly Carroll.

Intent on attending medical school immediately after graduating from the UO, Carroll’s research on the development of the enteric nervous system, which is the system the controls how your gastrointestinal system functions, changed her perspective.

“Participating in research has changed my aspirations,” Carroll said. “I came into undergrad thinking I’d go straight to medical school and I’d always be on that path, but participating in research has opened my eyes to the possibilities that are in the fields of medicine and science. It’s changed the trajectory I see for myself.”

Carroll works in the laboratory of biology professor Judith Eisen and said she hopes the research she’s contributed to will help in better understanding Hirschsprung’s disease, a congenital condition that results from missing nerve cells in the colon.

When not looking through a microscope to examine zebrafish, which share 70 percent of the genes that humans have, Carroll feels at home enjoying time with friends at Falling Sky in the EMU discussing things other than gut health.

Malyssa Robles

For one student, research meant taking feelings of fear as communicated through dance and translating them from an abstract, nonverbal form into the concrete words of a poem.

Malyssa Robles, a comparative literature major and dance minor, found the translation of her choreography into poetry stanzas challenging, but fascinating. At the symposium, a troupe of four dancers will perform Robles’ piece while she reads the poem, which will also be projected on a screen behind the dancers.

A self-described research veteran, she was first exposed to university research through her work examining the sociology around the need for a sense of control in the Nomad Mentorship Program in the Department of Comparative Literature. It was then, Robles said, that she learned that research requires networking, discipline and knowing the right questions to ask.

“I think what makes a good researcher is someone who is willing to be wrong,” Robles said. “It’s somebody who is willing to have their opinion changed, somebody who is willing to explore something they haven’t really explored much into. Research isn’t just for things that you have been studying for years and years. Research is for things that you’re looking to introduce yourself to, so I think that’s something that’s really important, for a researcher to be well-rounded and to be willing to delve into things they might not be so educated about.

While Robles has remained steadfast, never wavering from the major that she declared entering the UO, she says research gave her opportunities outside of her discipline.

“It’s been very interesting to branch away from the ideas that I created for myself and look into different disciplines and to find more of myself, not just as a person, but as a student,” she said.

—By Kimberly Lamke Calderon and Jess Brown, University Communications

For more, visit the undergraduate research edition of Oregon Quarterly