Curiosity about octopus brains earns grad student a prized fellowship

Angelique Allen will not only continue her research but also promote equity and inclusion in science

When neuroscience graduate student Angelique Allen isn’t climbing sheer rock faces or running science outreach events, she’s immersed in the brain of the octopus.

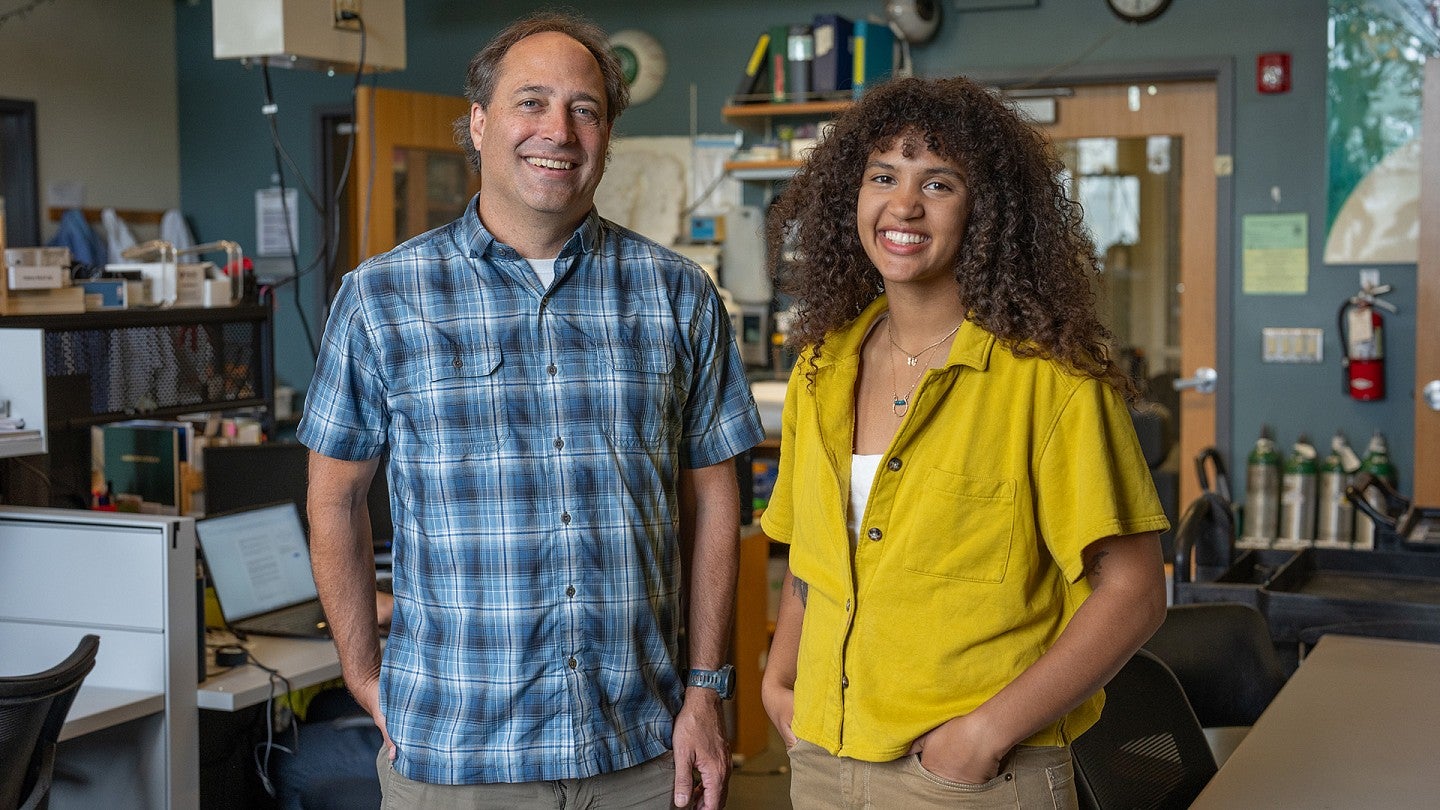

Her fascination with the way these many-armed animals see their underwater world led her to Cris Niell’s lab at the University of Oregon, in the Institute of Neuroscience. And now it’s led her to a Gilliam Fellowship from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, a competitive award that’s honoring Allen alongside Niell.

Unlike many funding opportunities for graduate students, which simply provide money for research, the Gilliam Fellowship also includes money specifically intended for outreach and community-building. The award also plugs Allen and Niell into a broader network of scientists, providing mentorship and networking opportunities.

“Receiving this award is both an honor and a large boost in my hope for the future of science,” Allen said. “HHMI has made it clear that doing high-quality science, and equitably disseminating science so diverse populations can access it, is important. It can feel overwhelming to propose big ideas that no one has ever attempted before, and while Cris has always been supportive, it is extremely motivating that HHMI believes this is as exciting as we do.”

Inside the octopus brain

Octopus brains are ancient, evolutionarily speaking. But they’re also big and complex, far more like the brains of vertebrates than their invertebrate close relatives. That makes them an interesting alternative model for brain structure and evolution — that is, understanding how neurons come together to support the many functions that allow an animal to move, sense, eat and reproduce.

“It’s this unique middle ground that nobody has covered and we don’t know much about,” Allen said. The field “is expanding so rapidly and in so many fascinating directions, so I am really excited to be a part of this growing community and to be able to ask questions that people have always wondered but were unable to answer at the depth that new technologies give us access to.”

“We’re going in with a curiosity-based approach,” Niell added. “We don’t know yet if we’re going to find something that might end up being useful for human health, or machine vision, or who knows what we’ll find.”

While her interest in the octopus brain runs deep, Allen had never actually seen one in person before she arrived at the University of Oregon.

Initially on a premed track during her undergraduate studies at the University of Missouri, she quickly realized she wasn’t interested in medical school or pharmaceutical research. Instead, as a McNair Scholar, she worked on a research project studying cognition in lizards and fell in love with understanding how animal brains work. Around the same time, she started learning how to scuba dive, which piqued her interest in marine animals.

When she met a neuroscientist who studies aging in octopuses, “I was like, whoa, this is how you combine these two worlds,” Allen said.

When Allen was accepted to the UO and finally made an in-person visit to Eugene, “it pretty instantly like felt like it could be home,” said Allen, an avid rock climber in her spare time. “Both because of the atmosphere scientifically and the very outdoor-oriented nature of Eugene.”

Research — and beyond

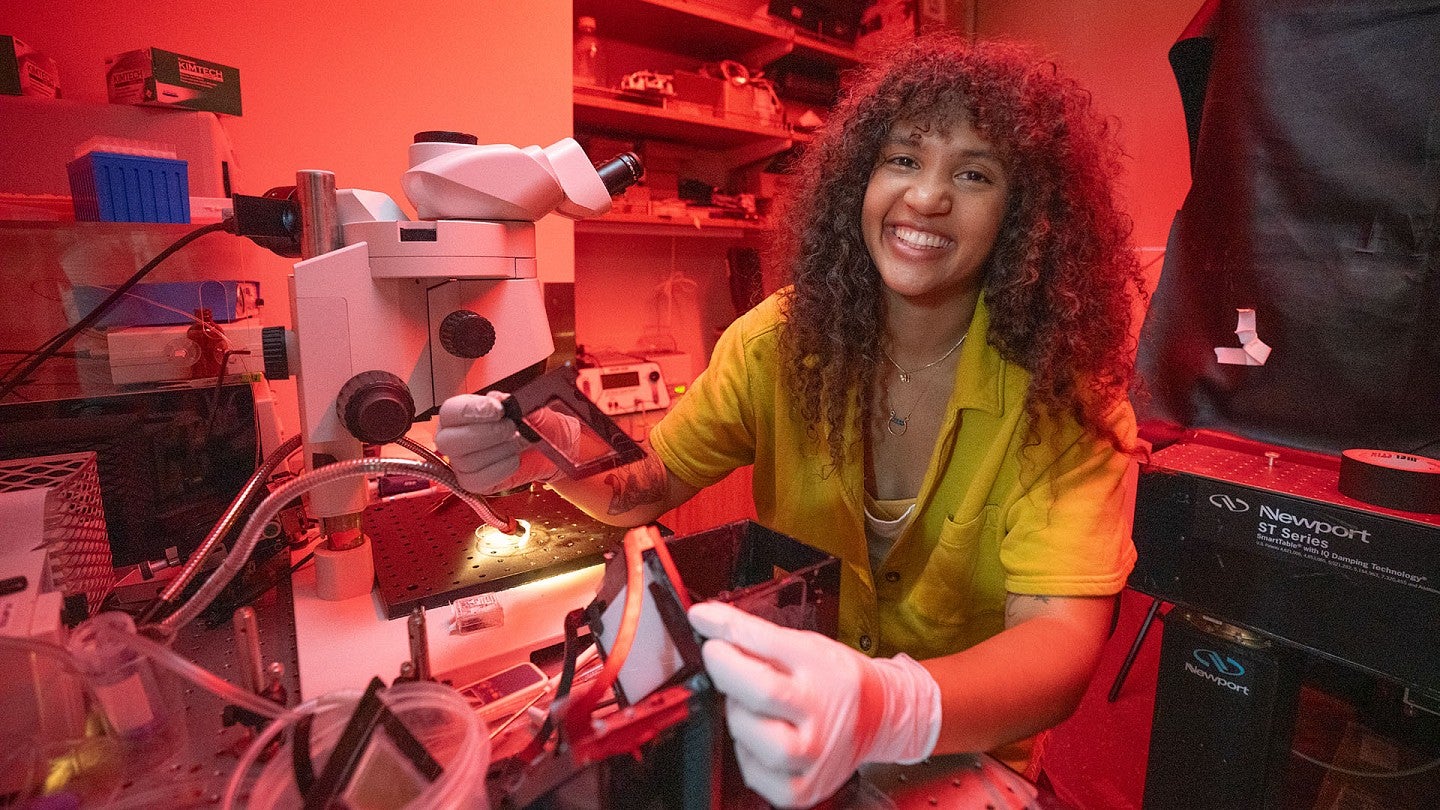

Now entering her fourth year in the Niell Lab, Allen will use the Gilliam fellowship funding to tackle two projects related to octopus vision.

In one, she’ll use two-photon microscopy, a specialized technique that can image brain tissue in high resolution, to map the octopus visual system. And in a second, she’ll use electrophysiology to study the individual firing patterns of neurons that support vision in the octopus brain and piece together the way they wire into circuits.

Together, the projects will help her understand how octopuses handle polarized light.

That could help them detect prey or even signal to other octopuses via patterns on their skin that are invisible to the human eye.

Allen channels her research passions into time outside the lab, too. She’s run science outreach nights at breweries around Eugene. And she’s working on writing a children’s book on animal vision, in collaboration with two undergraduate students who are helping with illustration and story research.

“The book is exploring this idea that animals experience the world differently but also highlighting scientists from underrepresented communities who are doing work to figure out the sensory worlds of other animals,” Allen said.

The Gilliam fellowship will give Allen and Niell $53,000 per year for three years, which will cover Allen’s graduate stipend, tuition and fees. And part of that money is specifically for Niell to develop a project that supports equity and inclusion in the sciences.

With input from Allen, Niell plans to use that money to create a mentorship program for first-year graduate students in the Institute of Neuroscience. New students will get paired with a more experienced student for peer support. The program also will include informal get-togethers to foster community and help incoming students find their footing.

The Institute of Neuroscience

The Institute of Neuroscience (ION) was founded in 1979 to advance visionary neuroscience research with an emphasis on collaborative, integrated studies. With faculty experts from the Departments of Biology, Psychology, Human Physiology, and Mathematics, as well as the Phil and Penny Knight Campus for Accelerating Scientific Impact, the institute comprises research interest groups focused on the areas of cognitive, cellular, and systems neuroscience and developmental biology.