Researchers unravel how a breast cancer gene affects fertility

The advance could one day lead to new treatments for those who carry harmful BRCA1 gene mutations

For those with a family history of breast cancer, BRCA is a household name. Women with a harmful mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes have a 60 percent chance of developing breast cancer at some point in their lives, and a many-fold increased risk of developing ovarian cancer. Men with mutations in these genes also have an elevated risk of breast cancer.

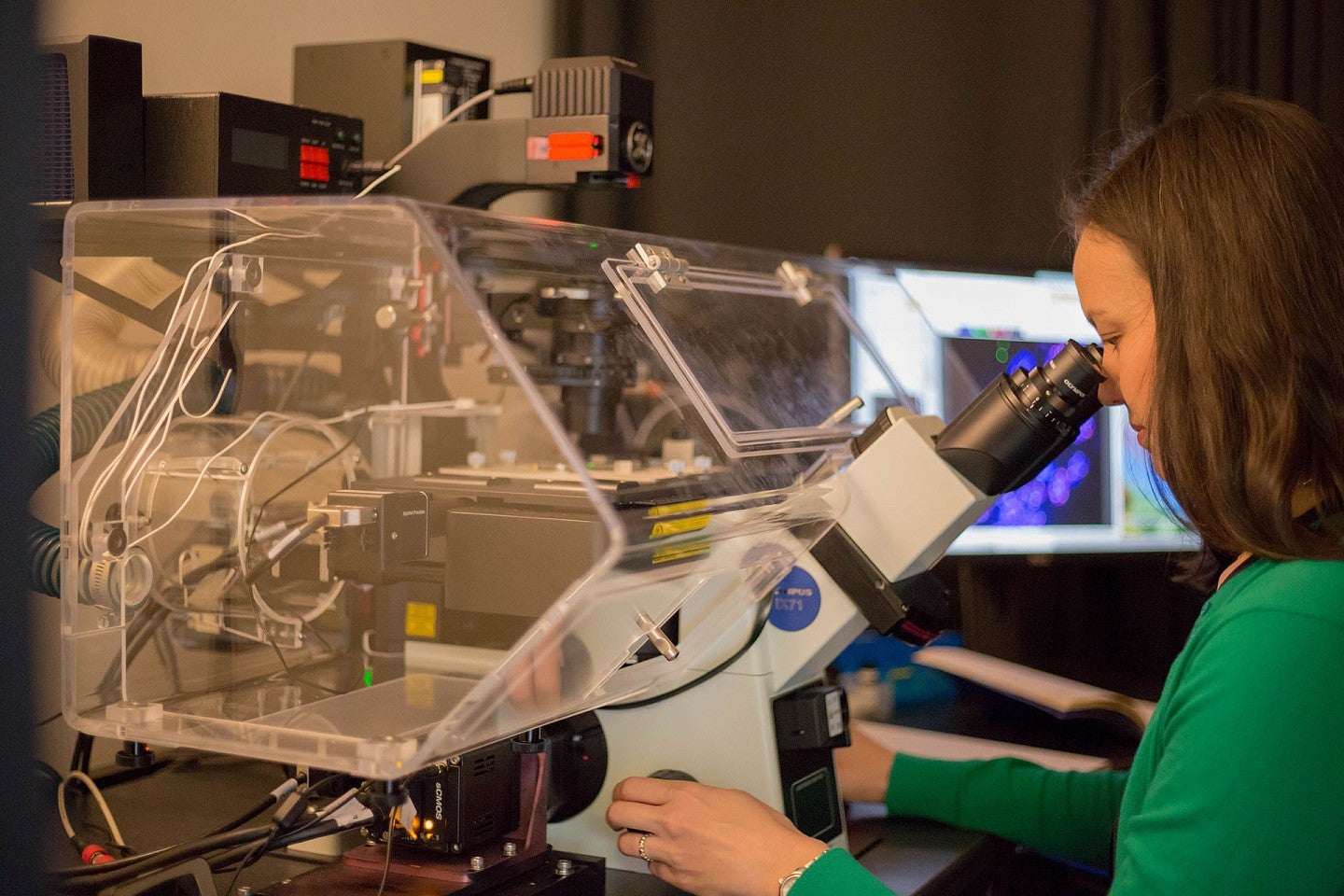

BRCA1 patients often face fertility challenges, too, beyond the side effects of cancer treatment. In new research, University of Oregon biologists have uncovered a mechanism by which the BRCA1 gene influences fertility.

“This is a breakthrough discovery that enables potential therapeutic avenues for understanding how to correct or treat fertility issues in BRCA1 patients,” said Diana Libuda, an associate professor in the Institute of Molecular Biology at the UO. “BRCA1 has been assumed involved, but the mechanism of how it’s involved was largely unknown.”

The gene plays an important quality control role during the specialized cell division process that makes eggs and sperm, Libuda’s team found. When BRCA1 is mutated and can’t perform this role, developing eggs and sperm end up with many genetic errors that can lead to infertility.

Treatments in humans are a long way off. But since infertility can have many different underlying causes, understanding what’s driving it in particular cases could eventually allow doctors to pick a more targeted treatment approach.

Libuda and her colleagues describe the finding in a paper published in September in the journal eLife. The study was led by Erik Toraason, a former graduate student in Libuda’s lab, and Alina Salagean, a former undergraduate researcher.

Worm wisdom

Libuda’s lab studies the molecular mechanisms of DNA repair during meiosis, the process by which egg and sperm are made. Errors during this process lead to genetic mutations in vital reproductive cells, which can then get passed down through generations or cause infertility.

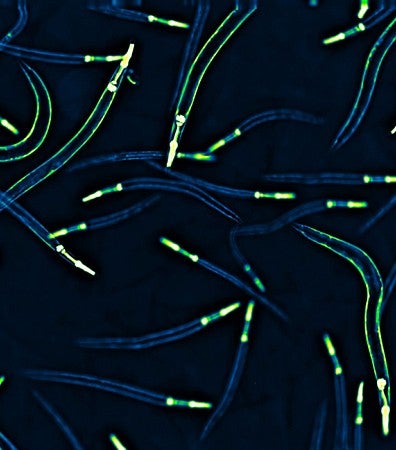

The lab conducts research using C. elegans, a tiny species of worm. Despite being the size of a pinhead, the worms share most genes with humans. That makes them excellent candidates for uncovering the genetic mechanisms behind key functions like reproduction.

In the worms, scientists can make genetic modifications and then quickly see how they play out over generations, research that’s impossible to do in human subjects but can have major impacts for medical research. In fact, the 2024 Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology went to researchers working with C. elegans, who discovered a new kind of molecule that affects gene regulation — a vital process that, when it breaks down, can lead to cancer, birth defects and many other complications.

Spotting repair errors

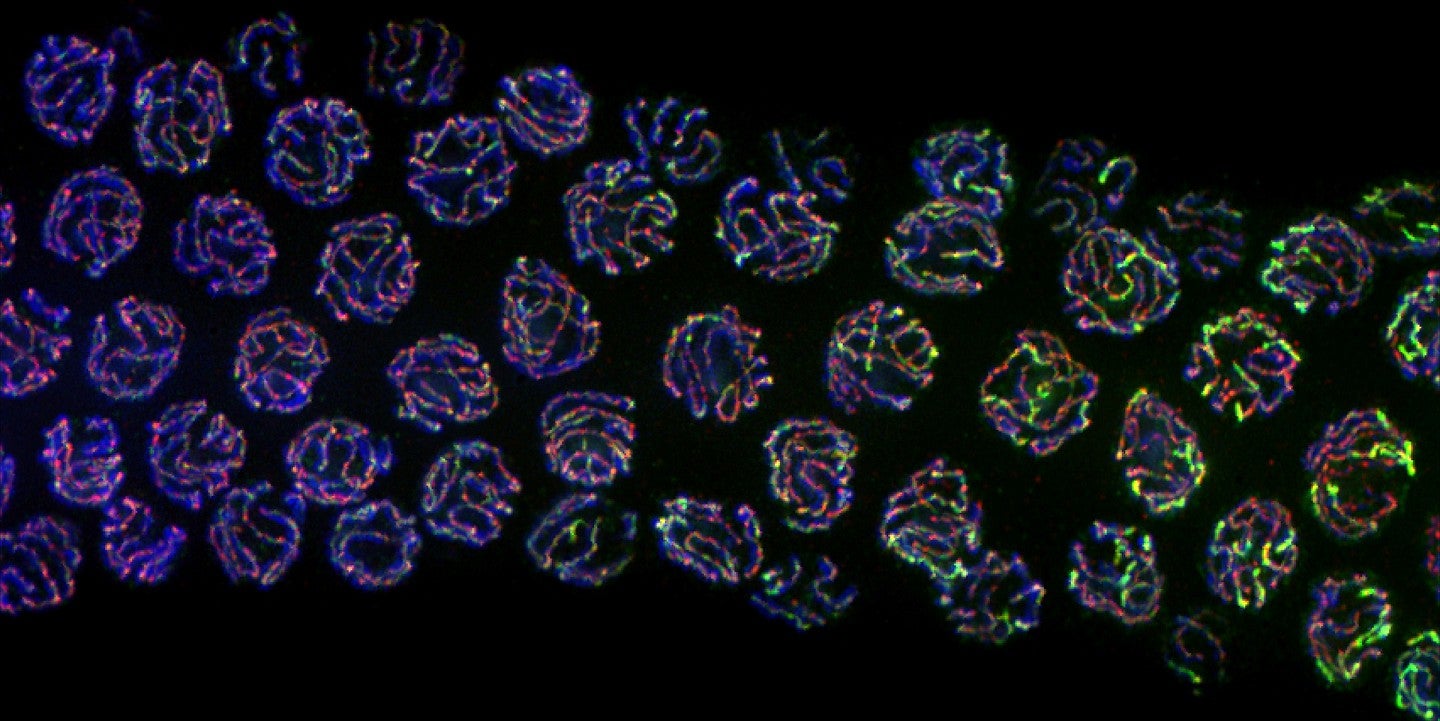

Egg and sperm cells have special mechanisms to repair DNA breaks that occur during their development. Those breaks are an essential part of sperm and egg formation, creating genetic diversity when chromosomes swap genetic information.

Usually, when DNA breaks and then gets repaired, the process leaves behind a tiny scar. But the repair processes during sperm and egg formation are normally seamless, leaving no genetic trace behind. That’s made them hard to study.

Then, a few years ago, Libuda’s lab developed a way to detect those invisible repairs, by breeding worms to have a gene encoding a fluorescent protein in a particular place. The gene is initially split, so it doesn’t work.

But when the DNA breaks and is repaired in that specific spot, the two halves of the fluorescent gene come together, and the worm glows. The researchers can tell whether a break and repair has happened by looking at which worms glow.

That approach has since allowed them to unravel how BRCA1 and other genes influence fertility.

BRCA1 shapes fertility

BRCA1 is a quality control gene during the process of egg formation, making sure DNA repairs happen in the right way, the team has shown. It tamps down a misguided DNA repair process that introduces scores of genetic errors via microdeletions of tiny snippets of DNA.

“These specific types of scars from the microdeletions are related to another pathway that is highly mutagenic,” Libuda said. “It’s thought to normally be repressed because it makes these microdeletions, which are bad. We found that BRCA1 is important for making sure that this pathway is not used.”

A person’s lifetime supply of eggs develops when they’re a fetus, so that’s when fertility problems like low ovarian reserve start, too.

“If you’re not repairing those breaks correctly, maybe those oocytes — cells that produce eggs — never come to maturity,” Libuda added.

Understanding these mechanisms and the size of their influence could help couples carrying BRCA1 mutations better prepare for fertility treatments, both financially and mentally. Someday, it might spur more targeted treatments.

Although BRCA1 is frequently associated with women’s health, breast cancer — and infertility — aren’t just female problems. Libuda’s team is now looking at how BRCA1 specifically affects sperm viability.

They’re also investigating other genes that might be involved in DNA repair during egg and sperm formation.

“Our BRCA1 study is proof of principle that our technology that we developed is a powerful system for understanding the mechanisms behind DNA repair,” Libuda said. “We’re looking at a whole bunch of other genetic players now.”

This work was supported by many funding sources, including the National Institutes of Health, the American Cancer Society and the Achievement Rewards for College Scientists Foundation.

Under the microscope

The Institute of Molecular Biology, located in the UO Lokey Science Complex, brings together biologists, chemists and physicists who collaborate to advance our understanding of the molecular foundations of living organisms.