Students get practical training while helping houseless people

With the help of visiting professionals, a team added a new, homey touch to Everyone Village

For architects, a threshold marks transition, a bridge between spaces.

For residents of Everyone Village, a transitional community for unhoused people in west Eugene, it’s a way to connect to the city while delineating their community — an intentional in-between gathering space unhoused people often lack.

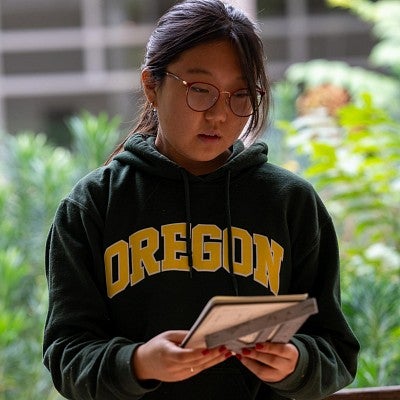

During the transition between summer and fall classes, 14 University of Oregon students created a new threshold for Everyone Village during the two-week Bruton Design Intensive.

Undergraduates majoring in architecture, landscape architecture, interior architecture and environmental studies joined forces to design and build the project. Organized by the College of Design, the program brings accomplished professionals to campus who lead students through the theory and practice of a design/build project.

Now in its third year, the Bruton Design Intensive offers students an immersive, full-time learning experience outside the routine of an academic quarter. For two weeks, students push creative boundaries and engage in problem-solving that spans disciplines.

They also wear hard hats, saw lumber and stick to a budget.

— Michael Zaretsky, associate professor and department head in the Department of Architecture

“We were delighted to find two superlative Bruton Design Intensive leaders this year. Ursula brings a wealth of experience in academic design/build and Marta’s work is focused on social justice. Both are well known in public interest design/build.”

Past the threshold of campus, west of downtown, where prairies blend with industrial zones, the design/build team spends a hot September day at Everyone Village looking, listening and learning. The students meet with villagers, as they call themselves, and tour the 3.5 acres with 70 tiny homes.

Everyone Village started in 2022 on donated land. Today, 65-70 villagers participate in the transitional housing community. High school students throughout Oregon have helped build the homes, which villagers call “cottages of hope.”

— Josie Paik, junior landscape architecture major

“It was great to learn about the philosophy and core values of Everyone Village. The villagers and staff feel very strongly about those and bring them to life. Hopefully, we can continue that in the structure we’re building.”

The village is self-governed and includes a garden, plus a shared kitchen and laundry facilities. A warehouse serves as an entryway, gathering space, computer lounge, dining hall and more.

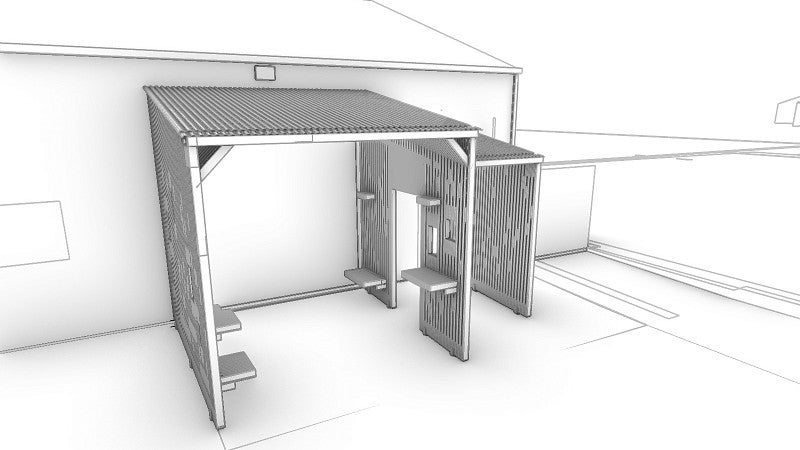

After learning more about the needs — and the life stories — of their clients, the students will design and build a threshold for the warehouse. Their structure will extend the two current gateways into the village: a large sliding garage door and the people-sized door next to it.

Students gain hands-on experience designing a project then constructing it, said Ursula Hartig, one of two visiting professionals who led this year’s intensive. Throughout the demanding process, everyone joins in the decision-making as well as the physical labor.

“You can't do life without collaboration,” said Hartig, who has more than 24 years of experience with academic design/build projects. “If you work together, you can achieve much more than you if you just add pieces.”

This collaboration has been multifaceted and multidirectional, added Marta Petteni, who helped with the Bruton Design Intensive in 2023 and joined as a coleader this year. That includes her partnership with Hartig, their engagement with the university, the interactions among the students and their collaboration with the villagers.

“This process represents a complex and dynamic convergence of diverse groups and stakeholders,” Petteni said. “We’re all working collectively toward a shared vision that addresses the needs and desires of the villagers.”

Petteni has worked on design/build projects worldwide and currently runs her own design firm in Portland.

— Oliver McKnight, senior architecture major

“It’s great to work with different people with diverse focus areas. There are a lot of moving parts, so it’s easy to get lost sometimes. But it all comes back to the structure, which puts all of us back on the same page.”

— Ash Carbin, senior architecture major

“I really enjoyed this concept of being able to build or design for people who are typically not architects’ clients. They do not have access to design justice. Affordable housing is something I want to work on in the future.”

The visiting professionals who lead the program make it work, said Michael Zaretsky, associate professor and department head in the Department of Architecture in the College of Design. They bring experience and fresh energy to an intense, enriching experience beyond classrooms and studios.

— Ursula Hartig, one of the two visiting professionals who led this year’s intensive

“I'm a design-build ambassador. It benefits the students to realize what they have drawn abstractly. It also benefits them to learn about the needs of their clients and go beyond their own mindset.”

— Ursula Hartig

- German-registered architect

- Former professor of architecture at Munich University of Applied Sciences

- Co-founder of CoCoon Studio

- Co-founder of the DesignBuild Exchange Network

- Taught design/build studios at Technical University Berlin, Munich University of Applied Sciences and Portland State University.

- Member of the executive committee of the Design for the Common Good network

— Marta Petteni, one of the two visiting professionals who led this year’s intensive

“Architecture is inherently political and never neutral. Design justice centers on empowering historically marginalized groups to lead the design and have power in the decisions that will ultimately affect them.”

— Marta Petteni

- Italian-licensed architect

- Co-founder of Portland-based Studio Petteni, a firm focusing on the social and environmental needs of vulnerable communities

- Codirector and project manager, AfroFuturism Oasis project in Portland

- Worked on design/build projects in Italy, Spain, Ecuador, Fiji and the United States

- Former Portland State University adjunct faculty member

The day after the students visit the village, a group of villagers comes to campus. The weather’s turned cold and rainy, and gray daylight fills a studio in Lawrence Hall with high ceilings and spacious windows.

They discuss the drawings covering the walls and review their goals, such as adding a welcoming entryway, making the village more visible and creating a gathering space. They ruminate over shade, shelter, security, flowers and electric lighting.

The students must balance lofty aspirations with the realities of time and money — and the laws of engineering and physics.

Most days run 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. throughout the week, plus some time on weekends. Some days, especially toward the end, go longer. Plenty of food and coffee is provided, and the work spills into mealtimes.

“Sometimes I get tired, but I’ve enjoyed every single day of the program,” says senior architecture major Raman Bajwa.

— Raman Bajwa, senior architecture major

“I’m used to working on my own in the studio, but for this we must work together. And you have to actually build it, which is a great responsibility.”

The students distill all the ideas, aspirations and priorities into one first draft. The conversations are candid, but productive. They don’t always agree, and that’s expected. Excellence, not ego, is paramount.

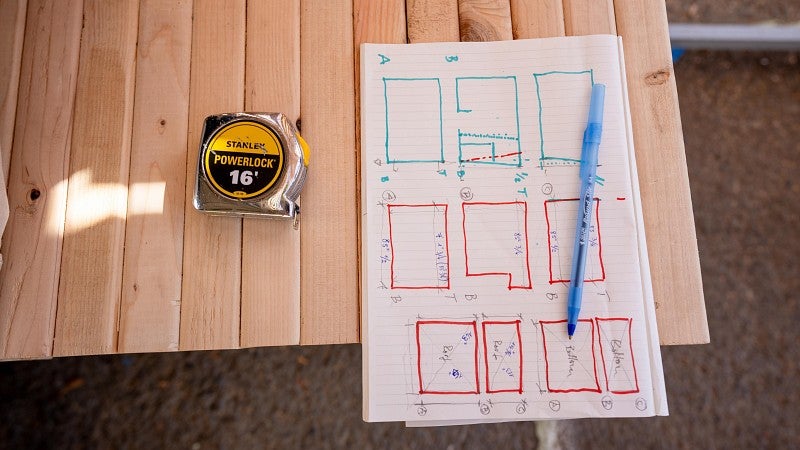

After refining the key concepts, the students break into three teams: structure, interiors and landscaping. Each team creates several drawings, presents them to the group, then polishes them into a final draft.

— Sriram Nathan, senior architecture major

“You’re going to butt heads. It’s inevitable with so many designers. You have so many things you want to include, but it’s not realistic to think you can do everything.”

However, as anyone who’s remodeled a home can attest, surprises can derail the best of plans.

For example, the disappointment in the room was palpable when Petteni announced that a swath of concrete could not be removed where the landscaping team had planned a garden space. Expect the unexpected. Embrace plan B.

“This program reflects the real world, just at a smaller scale,” says Larry Bruton, a 1967 UO graduate and retired partner with ZGF Architects. “You don't need a large budget to do something extraordinary. The real trick is to do something extraordinary with ordinary materials.”

Larry and Janice Bruton had already given generously to the UO faculty when the idea for the design intensive was first conceived in 2021. Larry spoke with Zaretsky and College of Design Dean Adrian Parr about inviting professionals to campus.

Asking a busy, successful architect to teach at a university for three months seemed unrealistic. But a two-week visit has turned out to be feasible.

The smell of fresh sawdust and the sound of applause fills the woodshop in Lawrence Hall. Environmental studies major Liam Martin has just cut the first of 400 two-by-fours with a miter saw.

It’s a good thing classes haven’t started yet, because the back of Lawrence Hall is full of bustling students shuttling two-by-fours — the only type of lumber used for the project — to different stations.

They measure, mark, move, stack, mark again, cut again and label each one. Like at a summer camp, the quiet reserve of the first day has dissolved into laughter and camaraderie.

The precut puzzle pieces are trucked to Everyone Village for assembly, where students in green and white hard hats assemble the structure. Over several long, busy days they transform their sketches into reality.

There are more surprises, like discovering the warehouse it connects to isn’t perfectly square. They adapt.

As the walls come together, they start to resemble slats of a miniblind. Vertical two-by-fours with equal spaces between them create a repeating zebra pattern: board-air-board. The outdoor structure feels open, creating shade while letting in light.

In some sections, the open spaces are filled in with shorter two-by-fours to create benches, shelves and patterns. Other sections of this painstakingly planned Jenga puzzle are left open to create windows.

The design/build team uses the word lamella to describe this technique of layering elements. Lamella also refers to the gill of a mushroom or mollusk. It’s a fitting term for a structure that adds natural wood to the metal and asphalt surrounding it.

It’s a rush to finish up before the Saturday afternoon ribbon-cutting. But the students form a well-oiled machine.

Some predrill the pieces with screws. Others call out the type of piece according to the catalogue codes they developed. Students with squares and levels double-check everything. All the pieces fit into place.

Minutes before the Saturday afternoon ribbon cutting — two ribbons, symbolizing the dual nature of a threshold — students scramble to put the final touches on the garden space. For fun, they test the rain chain with a bottle of water. A villager places a vase of sunflowers on one of the shelves of the new threshold.

Gabe Piechowicz, the village’s executive director, recounts the story of a recent newcomer who arrived seeking a safe space but was skeptical about entering the door of a nondescript warehouse.

“Now you’re going to be coming up to this beautiful, welcoming threshold,” Piechowicz says. “We will never be the same at Everyone Village, from today forward.”