UO graduate student Jonny Saunders wants to make technology more accessible to everyone.

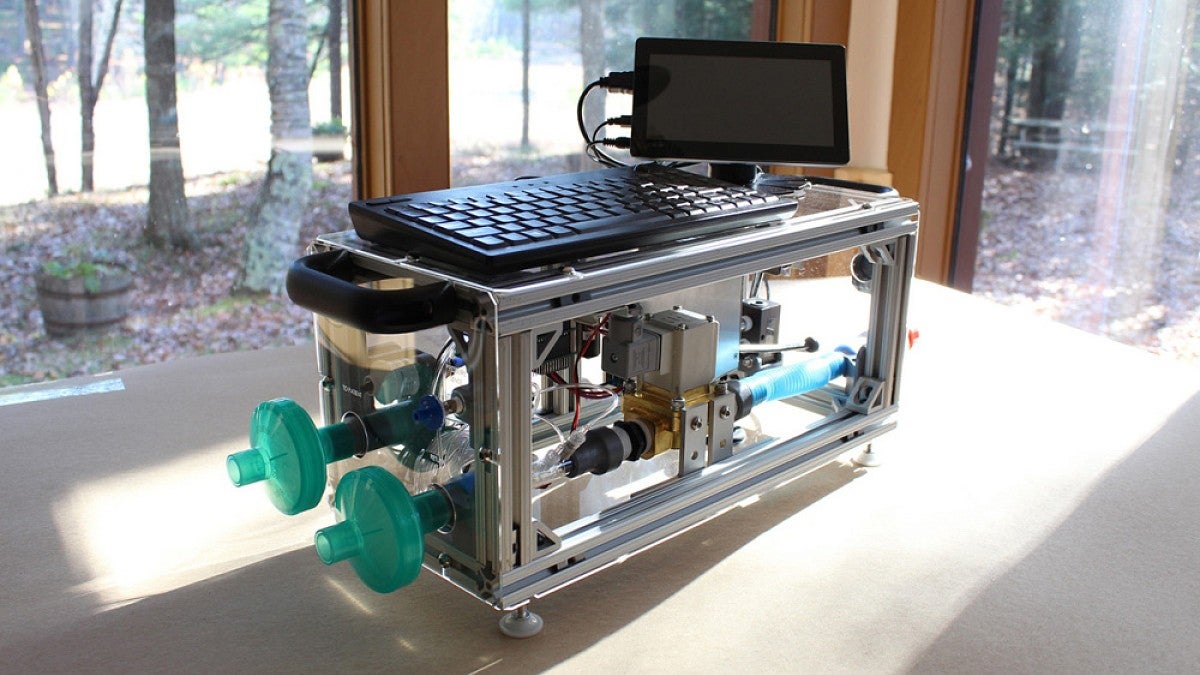

Since early 2020, Saunders has been working with the People’s Ventilator Project to design and build an open-source ventilator. The design can be built by a few people in a couple days, for about $1,300.

That’s a fraction of the cost of most ventilators used in hospitals, which can cost more than $30,000. The team recently published a paper in the journal PLOS ONE detailing the setup, and the full instructions and code are also available for free online.

“We’re bringing the spirit of open-source hardware and software to medical technology,” said Saunders, a graduate student in the Institute of Neuroscience.

The People’s Ventilator Project began in the early days of the pandemic, when it quickly became clear that that COVID-19 would strain hospitals. Shortages of key equipment such as ventilators were limiting care as extremely sick COVID patients crowded emergency departments and intensive care units.

A group of researchers at Princeton University and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute started working on a plan for a ventilator that could be pulled together from easily available components at a relatively low cost. When the team put out a call for someone to design the user interface, Saunders jumped in.

While the team initially hoped to create something that could be used as an emergency stand-in for overburdened U.S. hospitals, the complicated medical licensing process limited its progress.

Instead, team members decided to focus on something that could be deployed widely around the world, including in places with limited access to expensive commercial medical devices. Their goal: a ventilator that could be built quickly and affordably, with the ability to respond to pressure changes in patients’ airways and control how fast oxygen would be delivered.

To circumvent supply chain shortages, the ventilator uses very few medical-specific components. Instead, it draws on parts that could be easily purchased at a hardware store or from any electronics supplier. Saunders helped design and code the user interface and the alarm system, the parts that a medical professional would interact with while using the device.

“There are software challenges, but you also need to think of the social and cognitive challenges,” Saunders said. “Your code can be technically perfect, but the real question is whether a medical professional can understand it.”

For instance, a good ventilator should be intuitive to use, with menus and buttons laid out in a clear and logical way, and key settings easy to access. And its alarm system needs to alert doctors and nurses that something’s gone wrong, without overwhelming them with false alarms.

Saunders designed an alarm system that called greater attention to bigger and more urgent issues, by adjusting alarm tone, volume and timing. Saunders played with different user interface designs, too, getting feedback from doctors who regularly use ventilators.

“We did maybe 15 or 20 major revisions, working with doctors and consulting with different respiratory technicians to make sure that the interface would work as they expected it to,” Saunders said. “These are complicated devices, but it doesn't need to translate into a complicated interface.”

Because the ventilator design is open source, it can also be a useful tool for medical research. Researchers can edit the coding as necessary to better suit their needs. That’s difficult to do with commercial medical technology because the coding that makes them run is hidden and hard to manipulate.

While it began as a pandemic project, working on the ventilator has “changed the trajectory of what I want to do,” said Saunders, who ultimately wants to reduce gatekeeping in the tech world, building alternatives to platforms and technology controlled by major corporations.

“We can and should do more to use the accumulated knowledge and expertise we have, from being in science and engineering, so that so people can actually realize the benefits of the tech that exists in the world but is locked behind barriers,” Saunders said.

—By Laurel Hamers, University Communications