“Flexibility, Balance Draw Women to the University Of Oregon,” read the headline in the Oct. 14,1990, edition of The Scientist magazine. The story ticked off the names of a half-dozen UO women faculty members—many still active today—who were carving out careers for themselves and finding the UO to be an environment where they could thrive in traditionally male-dominated disciplines.

“The institute was quite unique and very well known for its fundamental research in genetics, molecular biology, and structural biology,” Barkan said. “I just felt so thrilled to be able to be part of this community.”

Barkan’s research focuses on genes that are required for photosynthesis—the process carried out by plants that produce the food we eat and the oxygen we breathe. Her work uncovered new mechanisms of gene regulation that are now being exploited for practical purposes, such as the production of biofuels and plant-based pharmaceuticals.

“How do the molecules that make up organisms work together to do what they need to do to make life work properly?” Barkan said. “That's pretty much what it all comes down to in molecular biology.”

“She has been an extraordinary advocate for our students in her many years of service as the director of the Genetics Training Program, member of the Department of Biology’s Graduate Affairs Committee, and most recently as IMB Director,” Guillemin said.

As a former director of the UO’s highly successful National Institutes of Health-sponsored Genetics Training Program, Barkan oversaw the training of promising graduate students from biology, chemistry, and math. Now in its fifth decade, the program creates the kind of cross-disciplinary research experience students and faculty members enjoy in UO’s centers and institutes.

“We really put our graduate students front and center,” Barkan said. “They don’t get lost in the shuffle. We bring them along and send them out the door prepared to succeed as scientists.”

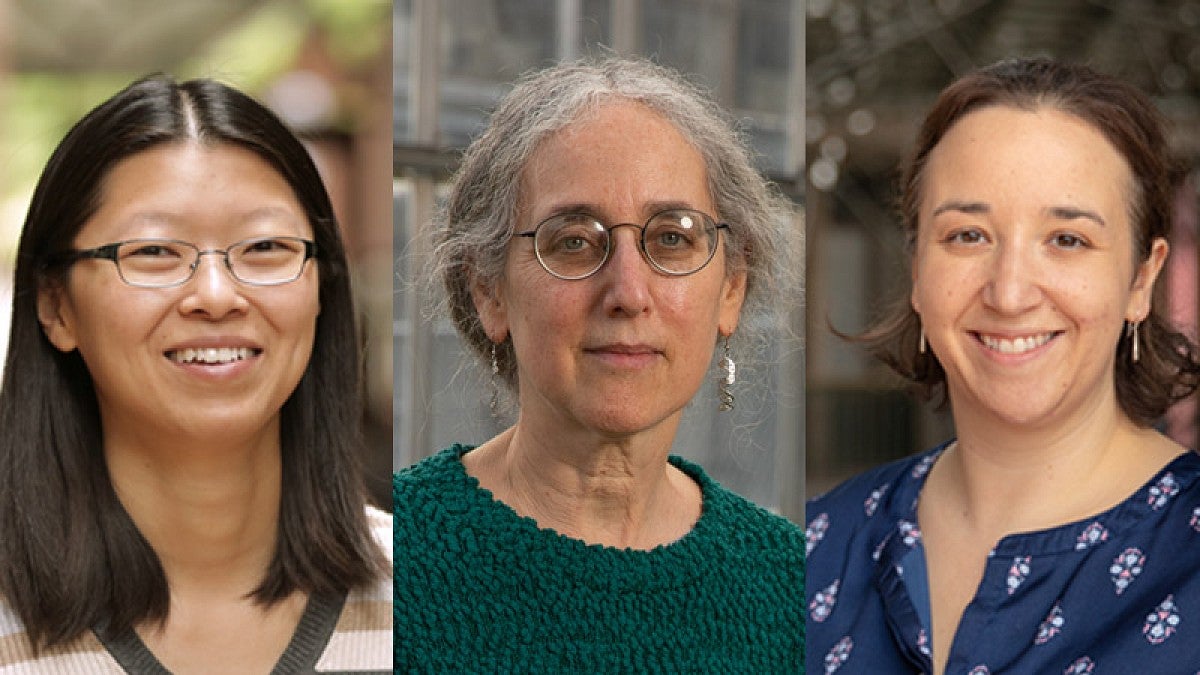

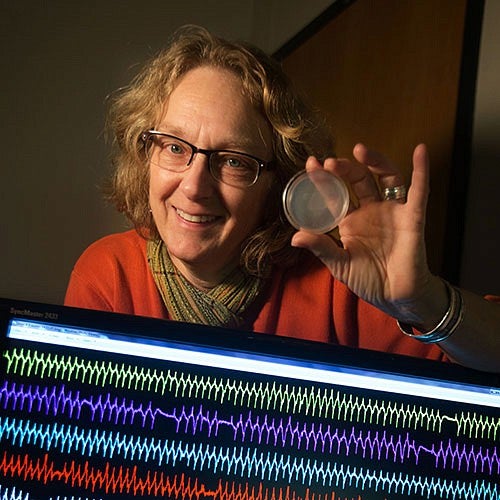

The Scientist Magazine story did not feature Barkan, who had yet to arrive at the UO, but it did highlight others who continue to achieve success—neurobiologists Janis Weeks and Judith Eisen and chemist Geri Richmond—while inspiring scientists like UO physicist Stephanie Majewski.

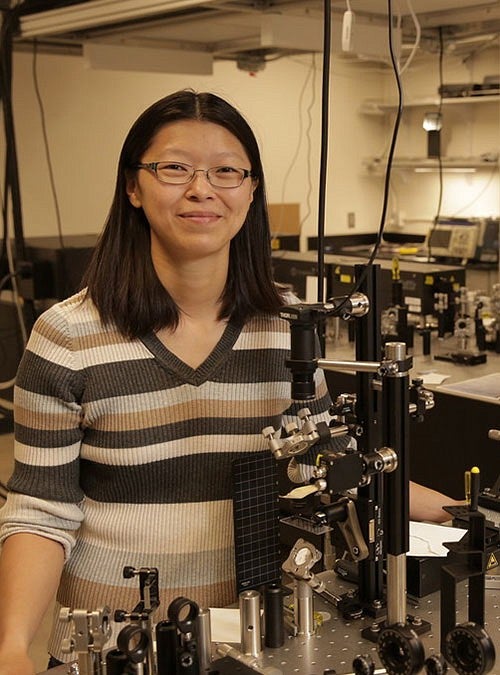

Like Barkan, Majewski was drawn to the UO by the high-powered science she saw taking place here. Now a tenured particle physicist, she joined the UO in 2012 and, in short order, received a prestigious Department of Energy Early Career Award and joined the UO team that contributed to the Higgs boson discovery at the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland.

“I definitely feel supported in the department, and I hope that my junior female colleagues feel supported, but it would be fantastic if we had five more women, or even a dozen more,” Majewski said.

“What makes me optimistic is just the fantastic female colleagues I see in the natural sciences,” Majewski said. “They’re doing amazing things that just blow me away and it’s exciting to celebrate their successes and cheer for each other.”

Chemist Cathy Wong was drawn to the UO by the camaraderie and supportive attitudes she saw among UO faculty members, both male and female, during her visits to campus.

Although Wong is in the busy tenure-seeking phase of her career, the National Science Foundation Early Career awardee somehow found time to sponsor a student group directed at improving retention for underrepresented minority graduate students in STEM departments.

Majewski, Wong, and Barkan all view advising and mentoring students as a critical component of their jobs. Hiring more qualified women faculty members in the sciences doesn’t just translate to better science but also means greater mentorship opportunities for women.

“I had a female PhD advisor and I think many women gravitate toward female mentors,” Barkan said. “I think that’s one of the most important reasons that having more female faculty will help nurture more female scientists in the future.”

Wong is inspired by the success of Barkan and other women faculty members, including her chemistry colleague Richmond, who founded COACh, a grassroots organization to help women advance their careers in STEM and combat discrimination in their fields. The organization has supported more than 20,000 women in the United States and developing countries around the globe.

Richmond credits Wong for tackling difficult scientific experiments and for recognizing the need to be a scientist on the national stage as well as on the local level.

“We need to make sure that our women are getting the kind of visibility that they need,” Richmond said. “Achieving national and international recognition takes work and often times women faculty are overlooked or others assume that they don't aspire to go to the higher level. We just need to be more proactive in sharing their talents with the world because we have some really, really good women here.”

When asked what’s kept her going all these years at the UO, Barkan falls back on the science that attracted her in the first place.

“Doing research can be frustrating, slow, and difficult, and if you don’t love it, if you aren’t super excited to see what that next result is or don’t have the motivation to push through the troubleshooting, then it’s probably not the right career for you,” she said. “But I have thoroughly enjoyed my choice and feel so privileged to have had the opportunity to do this, and in such a collegial environment.”

—By Lewis Taylor, a staff writer for University Communications