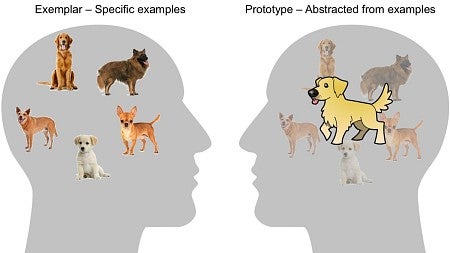

If the ideal dog in your brain is an abstract rendering of qualities drawn across many dog encounters, you are not alone in how your brain builds concepts, say two UO psychologists.

A new study by Caitlin Bowman and Dasa Zeithamova has put fresh eyes on a long-running debate about whether concepts are represented in the mind as a collection of individual events or as abstracts based on key characteristics generalized across specific examples to form a kind of prototype. The research also showed how one region of the brain has a bigger role than previously believed.

“Without knowing all the dogs someone has seen before, it may be difficult to tell whether people recognize a new animal as a dog because they rely on a comparison to specific dogs or their prototype,” she said.

For the study, published in the Journal of Neuroscience, the two researchers worked with 29 participants to probe how concepts are represented in the brain. They used artificial creatures as stimuli to examine what features the subjects processed and remembered. The cartoon images served as examples from two different concept categories.

Along the way the images were presented with slight variations, such as a different color; shape of the body, head, feet or tail; orientation of dots on the body; neck patterns; or directions the heads faced.

After training sessions, the participants were scanned in the MRI in the UO’s Robert and Beverly Lewis Center for Neuroimaging as they saw new cartoon animals and chose which category family was the best match for each.

This allowed the researchers to follow processing across the brain as decisions were made. They documented activity in brain regions known as the anterior hippocampus and ventromedial prefrontal cortex that was consistent with a retrieval of the prototype rather than specific concept examples. This finding suggests the hippocampus — previously considered a filing system for specific memories of individual events — has a role in conceptual memory formation.

“We watched conceptualization in action,” said Bowman, a postdoctoral researcher in Zeithamova’s lab. “We found that people form these abstract memories by linking across different examples. While the hippocampus has been thought to only represent individual memories, here it seems to work with the ventromedial prefrontal cortex to create these abstract memories.”

Returning to the canine connection, Zeithamova said: “You recognize a newly seen creature is a dog, because it looks like your neighbor’s dog or like the one that bit you the other day. This may allow you to remember specific events but also helps you put them together.”

Bowman, a graduate of South Eugene High School, returned to Oregon after learning that the Czechoslovakia- born Zeithamova had joined the UO. She made the move because their interests in memory formation are similar.

Bowman holds bachelor’s and doctoral degrees, respectively, from New York University and Penn State University. Zeithamova came to the UO in fall 2014 after completing a doctorate and postdoctoral work at the University of Texas at Austin. She holds a master’s degree from Charles University in Prague.

The research was supported by a grant to Bowman from the National Institutes of Health. Additional funding came from the Lewis Family Endowment, which supports the Lewis Neuroimaging Center.

—By Jim Barlow, University Communications