UO seismologist Diego Melgar can’t say that his first encounter with an earthquake launched his career. He was 1 year old when his family scurried into the streets of Mexico City during the 8.1 magnitude earthquake of Sept. 19, 1985.

More than 10,000 people died and 3,000 buildings were destroyed in the jolt that hit while the city was waking up.

Melgar later went off to college to study physics, but he dropped out. In his early 20s, he began reading about geology and earthquakes. He returned to college and “took a leap into geophysics.”

His calling is paying off.

His new paper in the journal Geophysical Research Letters has given his native country a new way to reassess earthquake risks and potentially improve hazard maps that guide building codes and readiness plans. It focused on the magnitude 7.1 Puebla earthquake of Sept. 19, 2017 — 32 years to the day after the 1985 event.

His geometry-heavy study uncovered a newly created fault line. It’s on land.

RELATED LINKS

The 1985 earthquake fit the norm in the country’s history. It was generated 250 miles west of Mexico City, just offshore where the Cocos Plate under the Pacific Ocean meets the North American Plate.

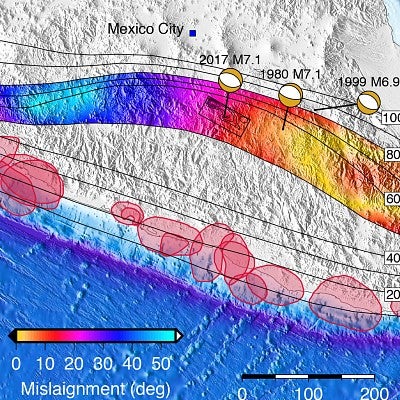

The epicenter of the 2017 earthquake was about 125 miles inland and 34 miles south of Puebla. It also was similar to quakes in 1980 and 1999 in that all had epicenters under land. Melgar and his team sought to find out why.

“This 2017 earthquake was a test for the national capabilities on rapidly reporting an event in a region with a relatively good station coverage,” said study co-author Xyoli Pérez-Campos, chief of Mexico’s National Seismological Service, who was 11 years old in Mexico City when the 1985 earthquake hit. “It also posed new scientific and social questions; of particular significance was how plausible it is to have a similar event closer to Mexico City.”

The researchers analyzed the plates’ subduction zone. Like in the Cascadia Subduction Zone along the Pacific Northwest Coast, Melgar said, the ocean plate is sliding under the continental plate.

Under Mexico, though, the subduction is bending in arc-like fashion. It dives at a steep angle to the north of Mexico City but more gradually to the south, creating what geologists call a flat slab.

The researchers also looked at slightly elevated hills on the seafloor that appear like lines of regularly occurring waves. They move outward as mid-ocean ridges spread apart in pulses. Under Mexico, however, the lines follow the bending, aligning northeasterly northwest of Mexico City and southeasterly from the capital on the flat slab.

“These hill lines record the rates at which the seafloor is being formed,” Melgar said, much like tree rings give information about age and growth rates. “By looking at them we can tell if seafloor is being made quickly or slowly.”

The researchers concluded that the flat slab, where the hills angle to the southeast, is a zone at high risk of land-based earthquakes. The deeper subduction region remains more at risk of traditional offshore-based quakes, Melgar said.

Mexico City is in “a hazy area,” he said, pointing to a small area directly south of the capital where a land-based quake conceivably could occur.

Melgar visited Mexico City in December. He walked the area damaged by last September’s earthquake, which killed 288 people and destroyed 40 buildings in his hometown, some 20 miles north of Puebla.

“Seeing the damage during my visit was a stark reminder that we can someday have an impact,” he said. “Being from Mexico, I know earthquakes are real. They are very present, much more so than they are here in the Pacific Northwest. In Mexico you feel them maybe once a year or every six months. Even if they are just a light jolt, they are always reminding you that they are there.”

The research was partially funded by a National Science Foundation grant that supports GPS and other sensing technology with Mexico’s National Council for Science and Technology and the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

—By Jim Barlow, University Communications