Jon Erlandson believes it was water, not ice, that opened the door for the first humans to make a home in the Americas.

A UO anthropology professor and internationally recognized authority on the archaeology of seafaring and coastal cultures, Erlandson has been at the forefront of a dramatic shift in thought surrounding the arrival of the continent’s first human residents. That shift — and what it means for future research — is the subject of “Finding the first Americans,” a perspective piece featured in a recent issue of Science magazine.

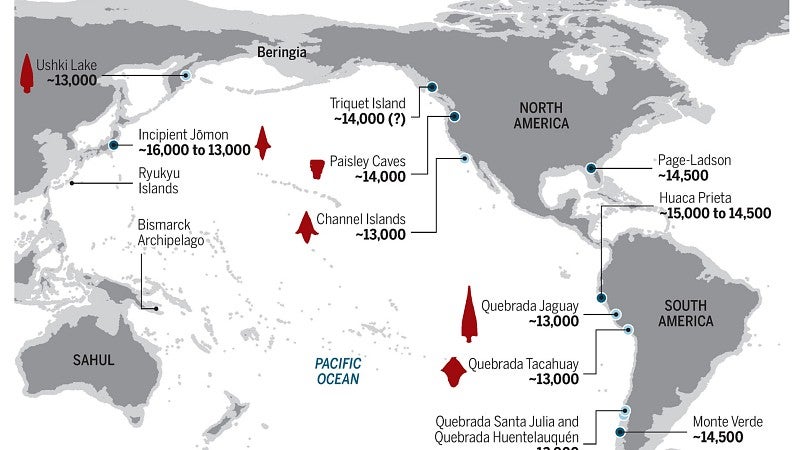

The study is coauthored by Erlandson, Tom Dillehay of Vanderbilt University, Richard Klein of Stanford University, and UO alumni Todd Braje of California State University at San Diego and Torben Rick of the Smithsonian Institution. The article re-examines the idea that the first Americans were big-game hunters who arrived around 13,500 years ago by way of an overland route from Siberia across a now-submerged land bridge across the Bering Strait. The hunters eventually headed south to the Great Plains via a narrow land corridor that opened as two vast Canadian ice sheets retreated.

Named the Clovis culture for a distinctive tool technology first uncovered at a site near Clovis, New Mexico, these explorers for many decades were regarded as the first to colonize the New World. But as the authors note, in the late 1980s the Clovis-first model began to erode when Dillehay reported findings from a site known as Monte Verde on the southern coast of Chile. There, Dillehay uncovered evidence of a human occupation dating to around 14,500 years ago — a thousand years before the appearance of Clovis people in North America.

“With Monte Verde, the Clovis-first model began to sink. Now it’s dead in the water,” Erlandson said.

The executive director at the UO Museum of Natural and Cultural History, Erlandson is known for his “kelp highway” hypothesis, which draws from his years of research at sites on California’s Channel Islands and elsewhere along the Pacific coast. It points to evidence that the first Americans traveled by water from northeast Asia following kelp-forest ecosystems around the Pacific Rim.

“Kelp forests from Japan to Baja California would have facilitated migration by seafaring people along a coastal route from Asia to the Americas well before an ice-free corridor opened in North America’s interior,” he said.

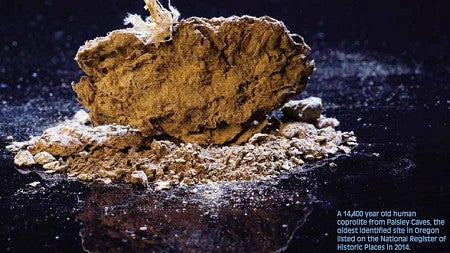

Seafaring people also were likely exploring and settling along major rivers with rich salmon runs, which would have offered corridors deep into the North American interior. These waterways may have carried them to the expansive wetlands of the Northern Great Basin, a region that straddles southeastern Oregon, southern Idaho and northern Nevada.

“Paisley filled an important gap in the coastal migration theory and made Oregon central to the study of the first Americans,” Erlandson said.

But even as scholars increasingly focus on coastal migration as the likely scenario for the peopling of the Americas, Erlandson and his coauthors note that the toppling of the long-held Clovis-first paradigm has created a vacuum. That has invited some extraordinary alternative claims, including those from a study published earlier this year in Nature magazine that purports to have uncovered a 130,000-year-old human occupation at the Cerutti Mastodon Locality in southern California.

“The implications of a North American archaeological site of that age would be staggering,” said Erlandson, “as the claims are quite at odds with the archaeological, paleoecological and genetic evidence to date.”

In addition to an overview of past and current ideas about the peopling of the Americas, the Science article offers perspective on key directions for future research.

“The main challenge we face in testing the kelp highway hypothesis is that much of the evidence of pre-Clovis coastal occupations would now be submerged by rising seas,” Erlandson said, “and the earlier such occupations may have occurred, the further off modern shores the evidence would now exist.”

What’s needed next, the authors note, is interdisciplinary field research focused on locating submerged archaeological sites.

“If the evidence exists, this is where we’re going to find it,” Erlandson said.

Erlandson is currently working on a $900,000 Bureau of Offshore Energy Management project that involves tribal partners, geologists, biologists and archaeologists from multiple universities in an effort to map sections of the seafloor off the coasts of California and Oregon. The project involves reconstructing submerged landscapes using on-land archaeological sites as models.

“These paleocoastal sites are often associated with geographic features like caves, springs, tool stone outcrops and natural overlooks with strategic views. We’re looking for similar landforms under water,” Erlandson said.

“It’s like looking for a needle in a haystack. We’re trying to make the needle bigger and the haystack smaller.”

—By Kristin Strommer, Museum of Natural and Cultural History