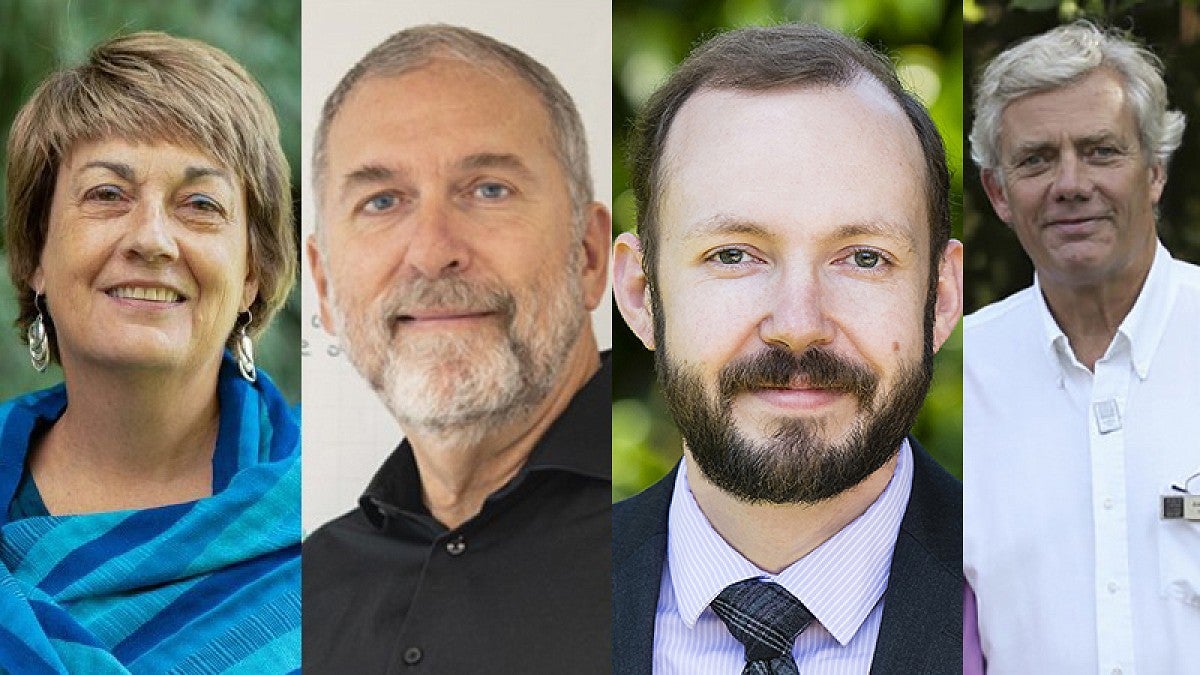

Four UO faculty members have been named as 2021 fellows by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, joining 564 other newly elected members whose work has distinguished them in the science community and beyond.

This year’s fellows and their areas of research are Lynn Stephen, anthropology; Mike Pluth, chemistry; Jon Erlandson, archaeology/anthropology; and Brendan Bohannan, biology.

“I am so pleased at the important recognition of these outstanding faculty,” said Cass Moseley, interim vice president for research and innovation. “It is a testament to the importance of research, innovation and scientific inquiry at the University of Oregon that researchers from these diverse fields are acknowledged at a national level.”

Transborder lives

Lynn Stephen, Philip H. Knight Chair and Distinguished Professor of Arts and Sciences in the Department of Anthropology, focuses on immigration and asylum in the U.S., gendered violence, race, transborder communities, Indigenous social movements, and diasporas from Mexico and Central America to the U.S., as well as Latinx community histories in the Northwest. Her current research explores access to justice for survivors of gendered violence and the effect of COVID-19 on farmworker health and well-being.

Stephen was cited by the association for “distinguished contributions to the fields of anthropology, Latinx and Latin American Studies, particularly for her theorizing and ethnography of Indigenous women, Indigenous migrants, transborder communities, migration and social movements.”

“Before moving to Oregon more than 20 years ago, I was doing research in a small Indigenous Mixtec community in Mexico when I saw a dozen pickup trucks that had Oregon license plates. That led me to write a book on transborder communities networked across many types of boundaries,” Stephen said. “I have been looking at connections, relations and histories between Indigenous, Latinx and other communities in the hemisphere ever since, with a focus on access to justice and the intersection between culture and politics."

Stephen added, “My research on asylum in the U.S. is connected to policy recommendations on how to improve the system, and my recent collaborative work on the impact of COVID-19 on farmworkers has been connected to recommendations for heat regulations, overtime and improved safety conditions for farmworkers through the Oregon state legislature and in a conversation with U.S. Labor Secretary Marty Walsh.

Beyond brimstone

Mike Pluth, a professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, uses synthetic chemistry to enable new investigations into the chemical biology of sulfide species. His research seeks to increase understanding of the fundamental chemistry of sulfur-containing species, including hydrogen sulfide and carbonyl sulfide, while creating an interdisciplinary and diverse lab environment.

Pluth was cited by the association for “distinguished contributions to the fields of bioorganic and bioinorganic chemistry, particularly for investigations into the delivery, detection and molecular recognition of reactive sulfur species.”

“We think about oxygen as being really important to life, but oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere is a pretty recent occurrence on the global timescale” Pluth said. “Earth’s organisms have vestigial cellular machinery that points to the abundance of sulfur that used to exist in the atmosphere. For example, hydrogen sulfide — a poisonous, rotten egg-smelling gas — is produced enzymatically in basically every living system and plays important signaling functions.

“Why did nature choose this poisonous compound to transmit signals? Things that are poisonous typically act quickly or are very reactive; our bodies harness that fast reactivity to only require a tiny amount of these molecules to transmit information. Increasing our understanding of how these compounds function has potential applications ranging from regenerative medicine to cancer therapeutics,” he said.

Sea change

Jon Erlandson, an archaeologist, emeritus professor of anthropology, and director of the Museum of Natural and Cultural History, studies the development of maritime societies, historical ecology in coastal environments, human evolution, and migrations and the peopling of the Americas. His current research centers on coastal archaeology, focused on sites being lost to sea level rise.

Erlandson was cited by the association for “distinguished contributions to the field of archaeology, particularly for reconstructing the history and paleoecology of maritime societies and advancing the kelp highway hypothesis for the peopling of the Americas.”

“Growing up in California and Hawaii, the theory that people only started living on coastlines or fishing intensively about 10,000 years ago never made sense to me,” Erlandson said. “An adviser once told me not to write about the coastal migration theory, that it could ruin my career. I did so anyway, chipping away at the wall of anthropological thought, and over the past 40 years there’s been a complete sea change. The dominant paradigm now for the initial peopling of the Americas is that people came down the coast.”

“Many people think archaeology is esoteric, but understanding historical ecology is where the rubber meets the road. There are great implications for restoring ecosystems and building resilience as the climate changes,” he said.

Traveling microbes

Brendan Bohannan, James F. and Shirley K. Rippey Chair in Liberal Arts and Sciences and a professor in the Department of Biology, studies the ecology and evolution of groups of microorganisms, or “microbial communities.” His current research focuses on why microbial communities vary from place to place and the implications of this variation.

Bohannan was cited by the association for “distinguished contributions to the fields of microbiology and ecology, particularly for demonstrating that there are general ecological principles that apply to all of life, both large and small.”

“Where my work has had the biggest impact is by demonstrating that tiny forms of life don’t necessarily play by different rules,” Bohannan said. “Now, we’re turning these ideas on particular communities of microbes that are associated with larger organisms like humans; we have entire rainforests of microbes inside us, known as our microbiomes. Why is your microbiome different from mine?

“Understanding both our individual microbiomes and how our microbiomes interact with the people we are in close contact with has important implications for the functions those microbes provide us and ultimately for our health,” he said.

— By Kelley Christensen, Office of the Vice President for Research and Innovation