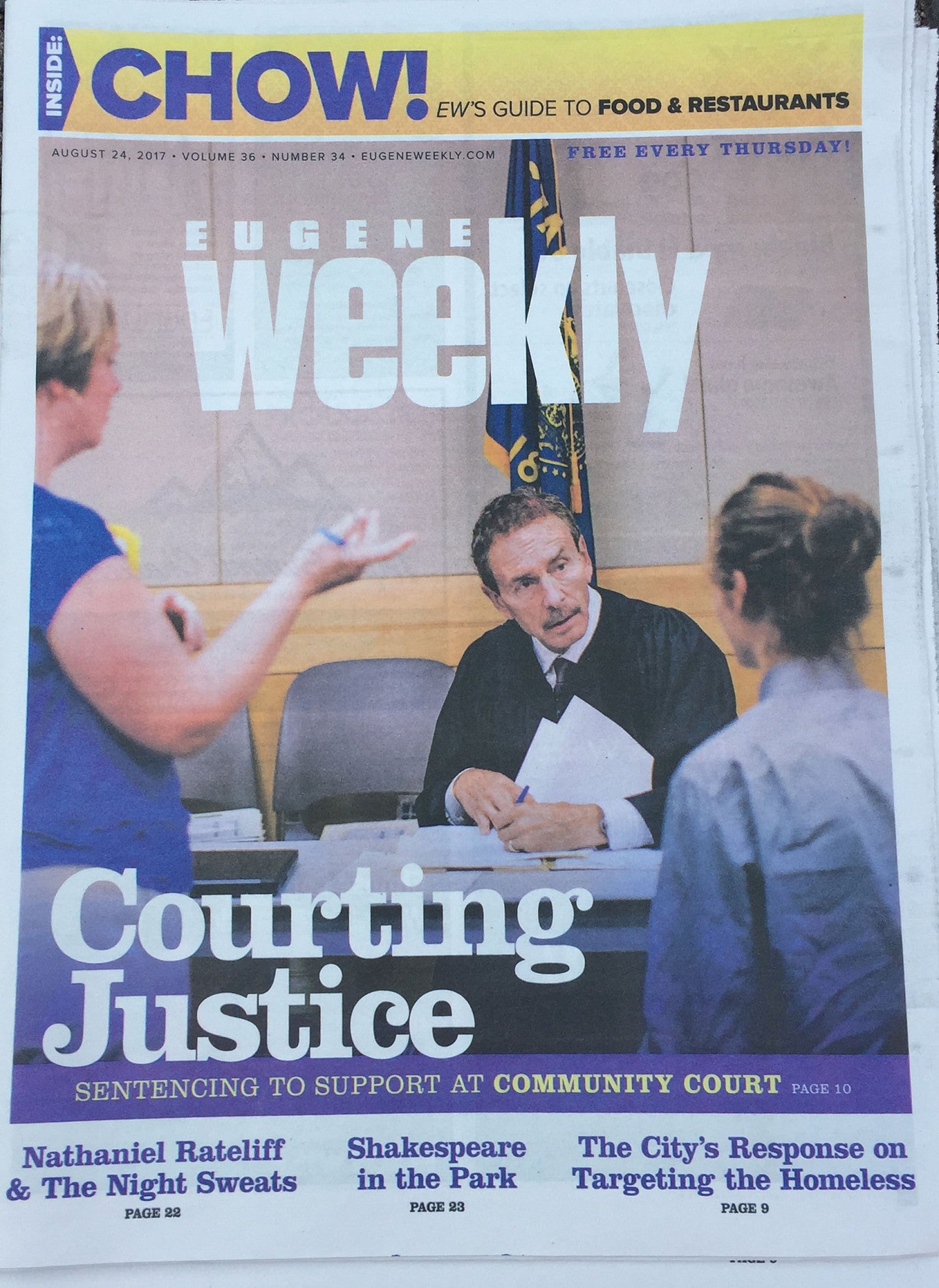

As journalism students at the UO last year, Kaylee Tornay and Brittany Norton landed a cover story in Eugene Weekly that addressed a workable response to both crime and homelessness.

During an investigative reporting course, Tornay discovered how often police arrested the homeless. She was in another class with Norton that taught them how to use their reporting skills to find workable solutions to civic problems. The result — their cover story on Eugene’s community court, which works with repeat offenders on underlying issues instead of relying on punishment alone.

This emerging approach uses evidence-based reporting tactics to examine potential solutions to societal problems. Catalyst integrates both teaching and academic research into its mission, as well as public lectures and discussions.

“People need to be aware of possibilities and not just limitations,” Tornay said. “I hope that the story helps readers understand that there are people positioned at the intersection of both problems who are having some success in mitigating them.”

Journalism instructor Kathryn Thier, associate professor Nicole Dahmen and assistant professor Brent Walth spearhead the project, which grew out of their conversations about the common goals shared by investigative and solutions journalism and their desire to help students publish in professional news outlets.

“We want to arm students with new reporting techniques and a strengthened mindset about how journalism can help sustain democracy,” said Thier, who was just named one of MediaShift’s top 20 innovative journalism educators. “Providing students with the opportunity to both study and practice this approach will position them to become leaders in a field that is struggling to find new ways to engage audiences.”

Walth, a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter, said that the best investigative journalism often includes reporting on ways to address the social problems it uncovers.

“The combination of these two methods seemed like an ideal fit,” Walth said.

Catalyst is garnering national attention and support. The Solutions Journalism Network, with funding from the Enlight Foundation, is supporting the project with a $185,000 grant. The funds will be used to support UO student reporting, solutions journalism curriculum development and multiday workshops to train university faculty members from across the country in the teaching of solutions journalism.

“Exploring the connection between investigative and solutions reporting is an especially important idea for journalism today,” said Keith Hammonds, president of the Solutions Journalism Network. “An investigative approach gives solutions stories ‘teeth,’ and a solutions lens, in turn, can add greater accountability to investigations. We’re excited to see the Catalyst Journalism Project expose UO students to this powerful frame. And we see it as a beacon for journalism-school education generally, helping to spur research on solutions journalism and build teaching capacity at other universities.”

Catalyst also received additional funding through teaching and research grants from the Tom and Carol Williams Endowed Fund for Teaching and the David and Nancy Petrone Faculty Fellowship. The research examines the process and effects of the investigative/solutions model to understand journalistic impact and build theory.

“Solutions journalism has the potential to help restore public trust in the media by making readers feel more informed, engaged and optimistic,” Dahmen said. “Instead of bombarding the public with doom-and-gloom news stories, it focuses on positive responses that have the potential to spark action on critical issues like environmental threats, gun violence, racial injustice, educational challenges and homelessness.”

Tornay said the combination of pioneering coursework and real-world experience makes a big difference in how she’s approached journalism, both as a student at the UO and as a professional reporter. She’s now employed by the Medford Mail Tribune, covering education and other local issues for the daily newspaper based in Southern Oregon.

“These courses taught us how to be rigorous in our reporting and how to use a critical eye to search for the whole story — when covering problems or solutions,” she said. “If journalism is really about telling stories that reflect the truth of a community, we should absolutely be able to ask, ‘What’s possible?’ and report it as effectively as we’re able to report stories answering, ‘What’s the problem?’”

That approach to reporting is a core component of the Catalyst Journalism Project’s curriculum. Students learn how to find and analyze evidence, think through limitations, consider the effectiveness of any given solution and ask questions that fully interrogate these responses to social issues.

Faculty members stress that solutions journalism does not offer silver-bullet fixes to such deep-seated issues, but rather it provides readers with a thorough examination of responses to societal problems.

“These stories don’t advise a ‘correct’ path,” Thier pointed out. “This type of reporting focuses on both what is working and what is not working, asking questions about why and how.”

“Investigative reporting often seeks to reveal secrets of civic importance that people in power don’t want the public to know,” Walth said. “One of the great secrets that solutions journalism reveals is that there are paths through problems that many people think cannot be solved. Bringing these two reporting techniques together is a powerful combination.”

—By Emily Halnon, University Communications