Sipping tea in a campus café buzzing with the caffeinated energy of finals week, assistant professor Ben Elias is taking a well-deserved end-of-term breather.

“Mathematicians are like abstract artists — no one understands us,” he said with a laugh. “Math has a terrible problem with outreach. Part of it is that you can't understand what math really is until you're a grad student, let alone the specifics of cutting-edge research. But we could do a better job explaining how we think, what we find elegant and beautiful."

Elias is certainly at the cutting edge. He and his research partner Geordie Williamson of Kyoto University were awarded a 2017 New Horizons prize for their work in representation theory.

The New Horizons prize is the companion award to the $3 million Breakthrough prize, the largest cash prize in science and math. Founded by a group of top Silicon Valley executives (including Mark Zuckerberg and Google co-founder Sergey Brin), the Breakthrough Foundation awards $25 million annually to researchers in math, physics, and the life sciences.

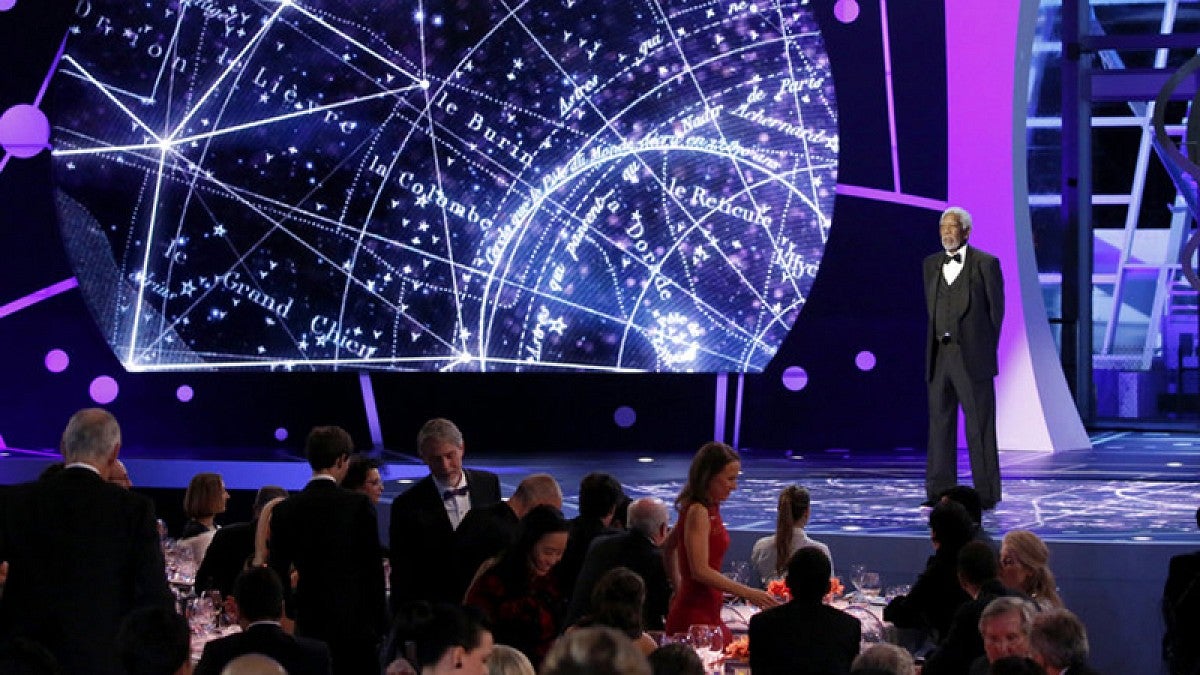

The ceremony was glittering and grand, featuring celebrity presenters such as Morgan Freeman, Alicia Keys and Jeremy Irons.

“The spectacle was fun and interesting,” Elias said with a smile, “but I don’t think (mathematicians) are its target audience.”

The goal, Elias said, is to give a spotlight to some of the world’s most exciting research and to hopefully inspire more people to enter the fields. “I think they’re hoping to fix the fact that most people’s heroes are sports stars and actors,” he said.

The New Horizons prize is specifically earmarked for early career researchers and recipients are chosen by a committee of previous winners. The list of honorees this year includes researchers from Stanford, Columbia, Princeton and Harvard, to name a few.

“For our math department, this is a big deal,” said Hal Sadofsky, associate dean of natural sciences in the College of Arts and Sciences. “It’s fantastic to have our department listed with these top names in science and mathematics.”

Elias’ specific area of focus, geometric representation theory, is only a few decades old. It originated in 1979 with a series of conjectures by David Kazhdan and George Lusztig. The conjectures were proven in some cases, but not all, by using geometric objects to understand symmetries. Elias and Williamson’s paper, published in 2014 in the prestigious journal Annals of Mathematics, expanded on the proofs to solve the conjectures in the general case.

“This is a problem that had been open for 35 years and had been worked on by many of the world’s leading mathematicians,” Sadofsky said. When the paper was published, Elias held a postdoctoral fellowship at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and was looking for a tenure-track position. Sadofsky, then head of the math department, knew he wanted to recruit Elias to the UO.

“People kept telling me about this brilliant young mathematician who might be interested in coming to Oregon,” Sadofsky said. With multiple researchers at the UO already working in Elias’s field, it was a perfect match.

“There are only so many universities in the U.S. with experts in this area,” Elias said. “The UO is one of the top schools in the nation in representation theory. These are strong researchers who stay in Eugene because they like the university and the atmosphere.”

Since the paper that garnered him so much attention, Elias’ research has mainly focused on Category O, one of the main families of setups in representation theory.

“Ben has done anything but rest on his laurels,” Sadofsky said. “His productivity has been unbelievable since he came to Eugene.”

To Elias, the gig hardly seems like work.

“Math is one of the more fun fields,” he said. “You just travel around, talking to smart people and solving problems together. You don’t have to fight for money, because there’s very little overhead. I couldn’t think of a better job.”

—By Katy George, University Communications