With support from a new $85,216 Library Services and Technology Act grant from the Oregon State Library, some of the university’s most priceless scholarly resources soon will become fully accessible to researchers worldwide.

For the first time ever, the UO Libraries’ collection of rare books will be readily searchable via a complete and accurate set of online catalog records. The grant will fund both library staff time and vendor digitization support for the project, which is expected to take about one year to complete.

RELATED LINKS

Manuscripts donor Julia Burgess recently named one of "100 Ducks Who Made a Difference"

Read more about highlights from the Rare Book Collections on Special Collections’ Unbound blog

See the full list of collections that will be cataloged

Plan a visit to the Special Collections and University Archives

“It’s an understatement to say we have a very rich collection,” said David de Lorenzo, the Giustina Director of UO Libraries’ Special Collections, who spearheaded the grant application process. “We have around 300,000 rare books in the library, but over 60 percent of them have not been cataloged. In many cases, we just don’t know what we have.

“The idea here is to make our rare books more discoverable not only for the community in Eugene but also for people on the other side of the world. And the way to do that is to make the records available online, in a self-serve format, in their entirety. The process itself is pretty basic but many years overdue. What was missing was the money to do it.”

Bruce Tabb, the UO’s rare books curator and public services librarian, has been working with the materials for more than two decades. Now close to retirement, he said the grant will help fulfill longstanding efforts to improve awareness and use of the priceless collection.

“For a number of years, I have been getting rare books into the online catalog piecemeal,” Tabb explained. “When I pulled uncataloged materials for people to use for their classes or for inclusion in a library or museum exhibit, when they were through using them I would send those books to our catalogers and have them added to the online catalog. I’m thrilled this grant will allow for a comprehensive approach, rather than just piecemeal.”

When people hear the term “rare books,” Tabb said, the first things they usually think of are handwritten medieval manuscripts or leather-bound first editions from the earliest days of the printing press. The rare book collection in fact is quite expansive, containing the earliest titles printed in Oregon, modern fine press publications, Asian art books collected by Gertrude Bass Warner, pulp fiction and magazines, miniature books, Victorian-era English literature and historical novels, and a children’s literature collection.

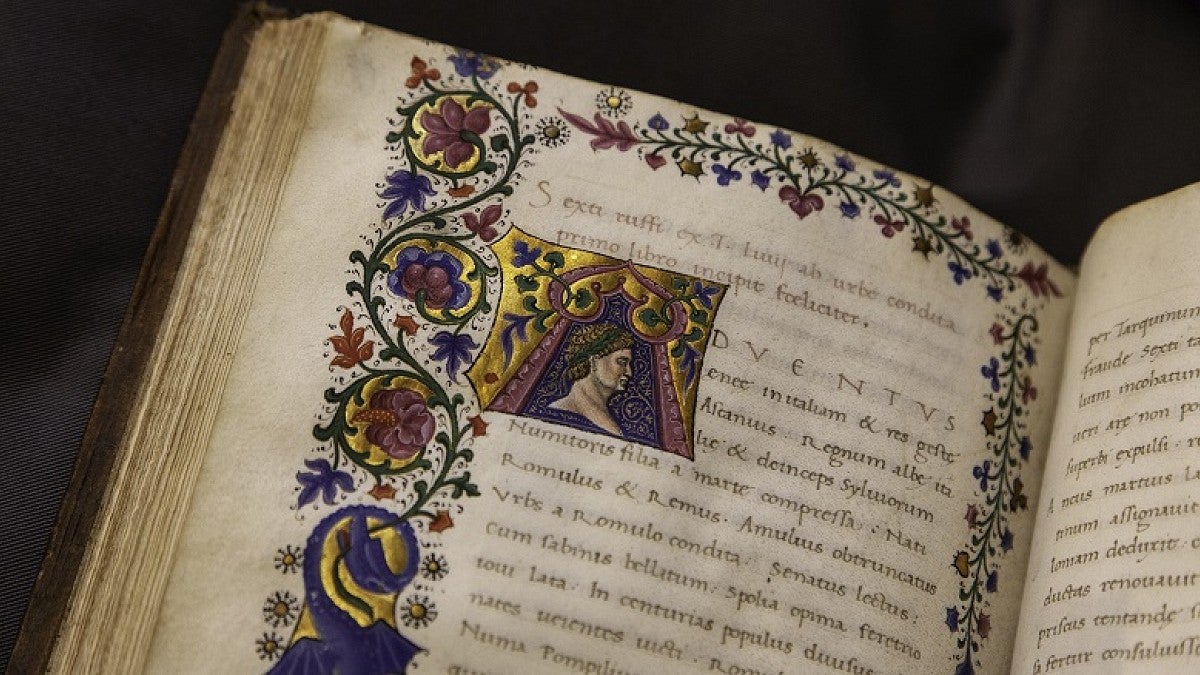

The foundation of the UO’s holdings is a cache of Western European and Near Eastern manuscripts that were donated to the university over the period of 1935-42 by Edward and Julia Burgess. In all, the UO holds 62 medieval and renaissance codices, 10 deeds and 27 leaves. It is the largest collection of these materials in any university library in the Pacific Northwest and the fourth-largest collection on the West Coast. Their donation also included 52 incunabula printed before 1501.

“These books aren’t just valuable now, they were incredibly valuable in their day,” Tabb said. “But rare doesn’t necessarily mean old, or even valuable.”

When deciding whether any newly acquired volume should be housed in special collections as a rare book or placed in the general, circulating library collection, the most important factor that Tabb considers is the research value of the work. Once this value is established, he then considers other factors such as the book’s age, scarcity, physical condition, provenance and presence of fine bindings or illustrations.

“A rare book can tell you a lot more than just the words on the page,” Tabb said. “There are parts of the book, as an artifact, that often tell you a lot more. Marginal notes by previous owners can make a copy completely unique, for example, or different editions of the same printing may have been put together and bound in different ways. Scholars often come to us more interested in some other aspects of these books, rather than just the printed contents.”

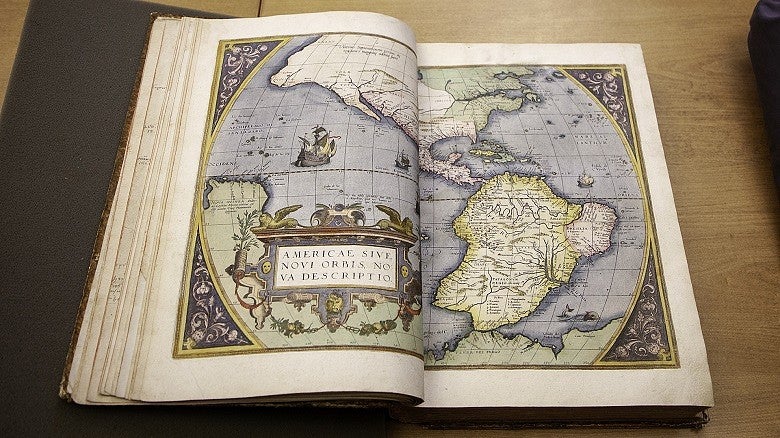

Gordon Sayre, a professor of English who specializes in 17th and 18th century narratives of travel in the Americas, has been using rare books in his research and teaching since he first joined the UO faculty in 1993.

“I was led on a tour through the special collections stacks in Knight Library by Bruce Tabb and compiled a list of a dozen or more books I was interested in,” Sayre recalled. “In effect, however, many of these books were completely lost because there was no index and no way to find them other than browsing the shelves.”

Sayre and an interdisciplinary cohort of faculty colleagues, including associate professor of history Vera Keller, visiting assistant professor of French Marc Schachter, and professor of English Elizabeth Bohls, later convened the Oregon Rare Books Initiative. Active from 2013-17, the group sponsored a series of public lectures by UO faculty members and visiting scholars with expertise in various areas of the collection.

“Our goal with ORBI was to call attention to the riches in the special collections and to encourage more UO faculty members to include the rare books in their classroom teaching,” Sayre said. “A distinctive feature of the ORBI talks was that we always had the books on display. We often would get a good number of book collectors or map collectors from the Eugene area. These materials hold interest not only for scholars but across the general public.”

Tabb agreed that rare books have a special, widespread appeal.

“Through the years I have really enjoyed sharing our collection with the public, faculty and students," he said. "Seeing their faces light up when viewing these materials has changed my view of humanity for the better.”

With help from the state grant, it is an experience more people around the world will soon have the opportunity to learn from and enjoy.

“Part of the deal of being a librarian is, we preserve the history of humankind and protect it from whatever machinations we can,” de Lorenzo said. “There will always be new ideas about how to look at things that happened in the past, because we as a society continue to change in our perspectives. That’s what keeps our library collections alive.”

—By Jason Stone, University Communications