A happenstance conversation in 2015 between a UO undergraduate anthropology student with his UO physics professor may have helped solve the mystery of how stone hats weighing up to 13 tons found their way atop Easter Island statues.

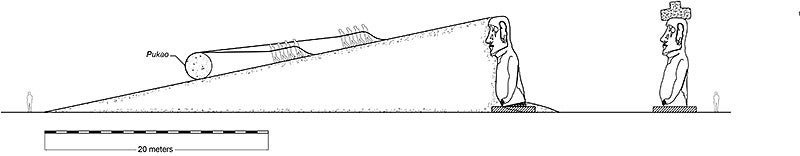

It appears, according to a new study in the Journal of Archaeological Science, that Polynesian travelers in the 13th century rolled raw materials from a quarry to the statues, finished carving the hats and then used ropes and ramps to roll them upward. The feat, the research team reported, could have been done with 15 or fewer workers.

The project, a mix of anthropological research, basic physics and 3D modeling, began at the UO.

Sean Hixon, now a doctoral student at Penn State University, was a student in the Clark Honors College at the time. On a research trip in 2014, Hixon, along with Terry Hunt, former dean of the honors college, and Carl Lipo of Binghamton University took 15,000 photographs of the hats and cylinders of material from which they were carved to see what attributes were shared and began contemplating how hats and statues united.

Once home from the island, also known as Rapa Nui, Hixon enrolled in a physics course taught by Ben McMorran. During a class exercise, McMorran said, Hixon brought up his honors college project involving the island’s moai, or whole-body, statues.

The statues, carved from volcanic tuff, came from one quarry. The hats, made of red scoria, came from a quarry that was 7.5 miles away on the other side of the island.

Previous research by Lipo and Hunt, now dean of the University of Arizona Honors College, determined that the statues — up to 33 feet tall and weighing 81 tons — were moved into place along well-prepared roads using a walking-and-rocking motion.

The hats, with diameters up to 6.5 feet, may have been rolled across the island, but once they arrived at their intended statues, they had to be lifted onto the statues' heads. The islanders probably carved the hats cylindrically and rolled them to the statues before further carving the hats to attain the final shapes, the researchers theorized.

"We were interested in figuring out the method of hat transport and placement of the hats that best agrees with the archaeological record," Hixon said.

Using measurements obtained with their photography and 3D imaging, the team created images of the hats with all their details.

The only common features were indentations at the bases of the hats, which fit the tops of the statues' heads. If the hats had been slid in place on top of the statues, then the soft stone ridges on the margin of the indentations would have been destroyed. So, the team thought, the islanders must have used some other method.

Previous researchers had suggested that the statues and hats were united before they were lifted in place, but remnants of broken or abandoned statues, and other evidence for walking the statues, suggested that the hats were likely raised to the top of standing statues.

Once rolled to the statues, Lipo said, the Polynesians likely set up ramps using a parbuckling technique. That’s a simple way to roll objects and has been used to right capsized ships.

The center of a long rope is fixed to the top of a ramp, and two trailing ends are wrapped around a cylinder to be moved. Rope ends are then brought to the top where workers pull on the ropes to move the cylinder safely up the ramp. At the top, the hat would have been tipped and rotated into place.

The National Science Foundation-funded project, HIxon said, was greatly helped by his conversations with McMorran and a teaching assistant in the Physics 252 course.

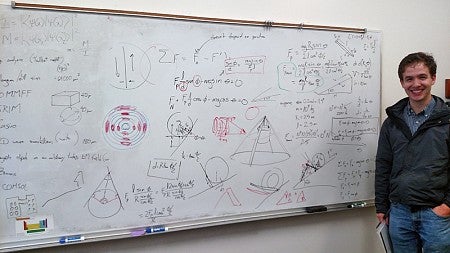

“Many of the fundamental concepts that we covered in class were important for identifying physically feasible methods of stone hat transport on Easter Island, and Ben was excited to think about the problem with me,” Hixon said. “Because we were both interested in the topic, we worked together on the whiteboard in his office over a couple of weeks. Eventually, the whiteboard was filled with sketches of the forces involved with different transport scenarios.”

That collaboration, Hixon added, fed directly to the group’s conclusions.

—By Jim Barlow, University Communications, and A'ndrea Elyse Messer, Penn State University News