Puberty is tough. Raging hormones, changing relationships, sexual awakening, risk-taking, exposure to alcohol and drugs, depression and contemplating the future. In developing countries, famine and new technologies add pressure.

The turbulent years of adolescence, especially during the onset of puberty, need more attention, say University of Oregon psychologist Nick Allen and three colleagues from the University of California, Berkeley in a paper published in the Feb. 22 issue of the journal Nature.

“Adolescence is a time of life when investments in health, education and well-being can have large pay-offs across the lifespan,” said Allen, an Ann Swindells Professor in the Department of Psychology. “But to make these investments wisely, we need to apply what scientists are learning about the changes occurring in the adolescents’ brains in relation to their behavior and social environments.”

Such investments, Allen and colleagues argue, could help teens forge a healthy trajectory.

Among key targets of such an initiative would be the early recognition and treatment of mental health issues, which tend to arise in adolescence and carry through adulthood, and new approaches that promote and encourage gender equality, Allen said.

In their paper, the researchers list several developmental changes that occur in adolescence and provide ideas for intervention strategies based on current science.

Investments might be reflected in tools used by schools, law enforcement, welfare services, family-support networks, and sports and recreation, Allen said. In lower-income countries, secondary education, especially for girls, should be made available, along with commitments to reduce exposure to HIV, famine and child-age marriages.

"The issue revolves around sensitive periods," Allen said. "In early childhood, there are certain times that are crucial for learning specific things. We have learned, for instance, that famine experienced during adolescence often has a lifelong impact on growth, much greater than famine experienced during other stages of life. This suggests that adolescence is a sensitive period for growth, but we believe that there are other critical sensitive periods relevant to adolescence, especially associated with learning the social and emotional skills to navigate the adult world."

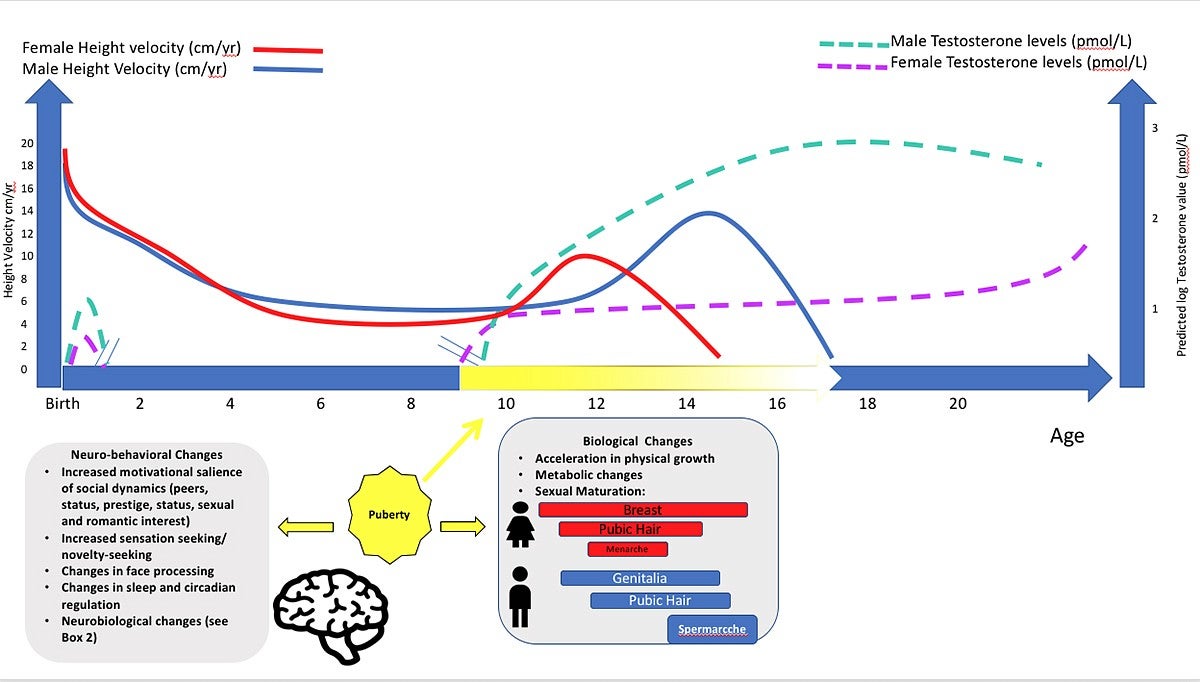

A lot has been learned about such things as brain development, language acquisition, vision and walking in the first three years of life, Allen said. Adolescence, however, involves hormone-driven physiological changes in combination with exposure to romantic relationships, status hierarchies, the concept of delayed gratification and setting long-term goals.

Why the urgency?

Teenage populations are higher than ever before, now at 1.2 billion and with 90 percent of the growth in lower- and middle-income countries, especially across Africa, Asia and parts of the Middle East.

In many of these countries, Allen said, technological advances such as the internet are just now arriving, setting the stage for rapid transformational changes in the social fabric, much like what occurred among teens in more advanced countries in the 1990s. Allen knows a lot about this topic through his role as director of the UO’s Center for Digital Mental Health.

Teens, Allen said, learn from experiences intuitively and implicitly. Those experiences need to be incorporated in the learning environment, he said.

“The emerging evidence points towards investments that place a strong emphasis on creating mastery learning experiences that maximize social learning and enhance status and autonomy at a key time in an individual’s development of social identity and competence,” wrote Allen, Ronald E. Dahl, Linda Wilbrecht and Ahna Ballonoff Suleiman in their paper.

Allen identified early adolescence, from ages 10-14, as puberty occurs as a pivotal time to target. Girls, because they hit puberty first, have a lot to gain, he said.

“This is a period when girls are physically larger and stronger, and often much better in school and in self-regulating, but what are the messages we are giving to young girls during this time?” Allen said. “Are we encouraging them to be bold, to be risk-takers, be physically active, to do things that typically have been associated with masculine qualities. We often are sending the opposite messages to girls.”

In early adolescence, he added, girls and boys experience a similar emergence of depression and anxiety, but by late adolescence girls have twice the rate as do boys.

“Why? What parts might be biological or environmental? There might be opportunities for socializing girls at puberty in ways that promote self-esteem and confident behaviors,” he said.

The researchers see a triple dividend. Adolescents would get direct support in navigating their teen years. They would be in better shape as adult. And those successes would benefit the next generation as today’s teens become parents.

—By Jim Barlow, University Communications