The onslaught of gun violence in America seems never to end.

This year alone, at least 247 mass shootings — in which at least four people are shot, including survivors and shooters — have occurred, most recently and most notoriously in Buffalo, New York, and Uvalde, Texas, according to the Gun Violence Archive.

In the face of such violence, people react with horror and anger, sadness and shock, feelings that fade until the next shooting.

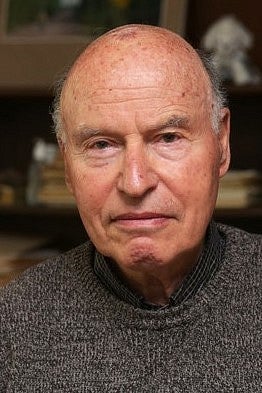

But in reality, people have more power than they realize, he said. That initial sense of helplessness is what Slovic and his colleagues call pseudoinefficacy.

The brain operates in two ways, one fast and one slow, Slovic said. The fast way of thinking is a gut reaction to events, the same response people might have experienced when they lived in caves and encountered a dangerous animal or unsafe food or water.

“It’s a sophisticated way our brain operates, but it sometimes fails us,” he said.

The slow way of thinking is scientific and analytic, using data and evidence, argument and reason. If ever society is going to deal with scourge of gun violence, people need to use the slow way of thinking, he said.

Those who react quickly in opposition to the idea that assault rifles should be restricted or regulated should move away from their immediate gut reaction and ask whether, as a society, people should tolerate young people, usually young men, some not old enough to buy beer, being able to go buy such weapons, Slovic said.

“Why should we tolerate that? There’s no reason for this,” he said.

Politically, people should think slowly and analytically, and when something egregious happens, support and pressure political representatives to enact legislation to address the problem. To be more effective, people can support organizations dedicated to gun safety.

“There is power in numbers,” Slovic said. “These organizations need our money and energy to help them. We can amplify our efficacy by joining forces with others who are similarly concerned and dedicated to this problem.”

RELATED LINKS

Mass shootings do break through the numbing that often accompanies high-casualty events, particularly when the personal stories of the victims become public, as has happened with the children trapped in their school in Uvalde, he said.

“There’s a lot of emotionality there, but it may not last,” he said.

Slovic has spent his career studying how humans make consequential decisions. His body of work was recognized earlier this year when he was awarded the 2022 Bower Award and Prize for Achievement in Science by the Franklin Institute.

In the face of calamity or tragedy, people’s feelings don’t scale up very well, he said. If an individual is in distress or at risk, people can empathize and care and value that person’s life. But as the number of lives at stake increases, people lose the ability to feel empathy.

“One person whose life is in danger is immensely important to us,” he said. “We care and will try to help … but our feelings don’t do arithmetic very well.”

As the numbers increase into the tens or hundreds of thousands, those numbers “bounce off our brain,” and people have difficulty comprehending the reality of 100,000 lives lost. Compassion begins to fade quickly, even when the number increases from one victim to two.

In other words, Slovic said, “The more who die, the less we care.”

The term for this is psychic numbing, coined by Robert Jay Lifton after the United States dropped atomic bombs on Nagasaki and Hiroshima. One way to overcome the feeling is to think about how human minds work.

A particularly striking example of psychic numbing came in 2015 when the Syrian government was murdering citizens opposed to its regime.

“Two hundred and fifty thousand people had died and millions had fled the country, but no one seemed to care about it,” he said.

That changed when a single news photo was published, showing a dead Syrian refugee child named Aylan Kurdi face down on a beach. The image galvanized world reaction.

“That picture woke people up,” he said. Donations to some relief organizations increased 50-fold overnight.

“When seeing a powerful image like this we become emotionally engaged, and ask, what can I do?” Slovic said. “If we can do something, we do it. If not, we go back to sleep and focus on other things in our lives that need attention.”

The shocking event gives a short window of opportunity to act. If society doesn’t act quickly, the opportunity for change will be lost, Slovic said.

On his website “The Arithmetic of Compassion,” Slovic and colleagues offer seven ways to overcome psychic numbing and feelings of inefficacy and become more compassionate, including becoming aware of the ways the mind misleads, raising awareness in others, connecting with people in need and organizations that help them, and understanding that, even if the entire problem can’t be fixed, partial solutions can make an important difference.

—By Tim Christie, University Communications