A gelatinous sea creature could teach engineers a lesson or two.

Nanomia bijuga, a marine animal related to jellyfish, swims via jet propulsion. A dozen or more squishy structures on its body pump water backwards to push the animal forward. And it can control these jets individually, either syncing them up or pulsing them in sequence.

These two different swimming styles let the animal prioritize speed or energy efficiency, depending on its current needs, a team of UO researchers found. The discovery could inform underwater vehicle design, helping scientists to build more robust vehicles that can perform well under a variety of conditions.

The UO team, led by marine biologist Kelly Sutherland and postdoctoral researcher Kevin Du Clos, report their findings in a recent paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Most animals can either move quickly or in a way that’s energetically efficient, but not both,” Sutherland said. “Having many, distributed propulsion units allows Nanomia to be both fast and efficient. And, remarkably, they do this without having a centralized nervous system to control the different behaviors.”

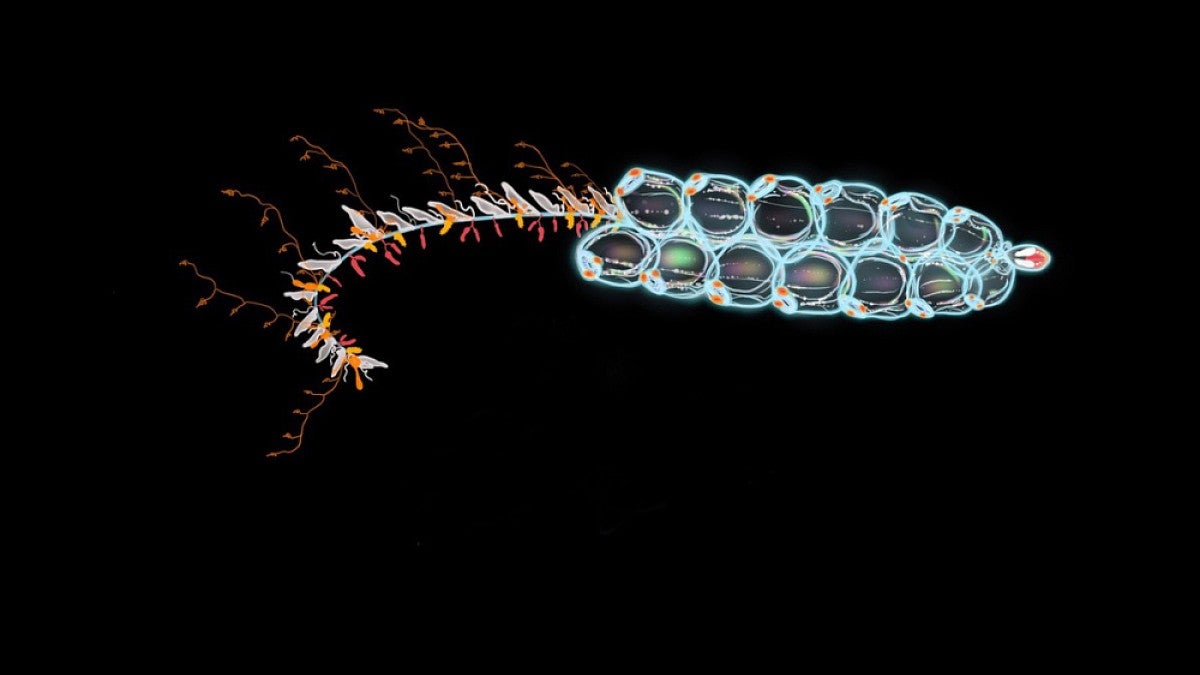

Nanomia shares the gelatinous, ethereal form of its jellyfish relatives. But it’s a little more structurally complicated: Each one is technically a colony of individuals. For instance, each of Nanomia’s jets is produced by an individual unit called a nectophore. The nectophores are clustered on a stalk-like structure at the front of the animal. Meanwhile, wispy tentacles trail behind, carrying structures specialized for feeding, reproduction and protection.

While many marine creatures move via jet propulsion, squid and jellyfish included, most just have one jet. Nanomia often has 10 to 20, the exact number varies colony to colony.

“We're interested in why multijet swimming is useful, and what we were really interested in here was the timing,” Du Clos said.

Nanomia can pulse its nectophores all at once or activate them in a sequence. Du Clos and his colleagues wanted to see how those different modes affected the animals’ swimming style, possibly illuminating an evolutionary advantage to having multiple jets.

At Friday Harbor Labs in Washington, the researchers scooped Nanomia out of the ocean and put them in tanks in the lab. Then they used video recordings and computer models to analyze the swimming patterns.

The two different swimming modes are suited to different situations, the team found.

Synchronous pulsing sends Nanomia forward very quickly, perfect for an expeditious escape from a predator. Asynchronous pulsing moves the animal a little more slowly but more steadily, and the researchers’ modeling experiments suggested that it’s a more energy-efficient way to swim. So with Nanomia sometimes traveling hundreds of meters per day, asynchronous pumping might be better suited for everyday use.

The intricacies of Nanomia’s movement could be useful for engineers turning to nature for inspiration.

“It gives a framework for developing a robot that has a range of capabilities,” Du Clos said.

For instance, an underwater vehicle could have multiple propulsors, and simple changes in propulsion timing could allow that one vehicle to move either quickly or efficiently as the need arises.

In future work, the researchers plan to dive more into Nanomia’s features, next focusing on better understanding how the arrangement of the animal’s tentacles affects its feeding.

Colonial animals are quite common in the open sea due to their potential hydrodynamic advantages, Sutherland added. The team is currently looking beyond Nanomia at other species of colonial swimmers, to figure out how diverse arrangements of swimming units influence animals’ movement.

—By Laurel Hamers, University Communications