The colonization of the far-flung region of the Pacific known as Remote Oceania, which occurred some 3,400 years ago, represents one of the most ambitious and expansive population dispersals in human history.

Seafaring settlers traveled hundreds — even thousands — of miles, navigating by stars and overcoming ocean currents and difficult weather for months to arrive in a region that includes present-day Tonga, Samoa, Hawaii, Micronesia and Fiji.

“Where did these people come from? How did they get to these really remote places, and what were the factors, culturally, technologically and politically that led to these population dispersals?” Fitzpatrick said. “These are really big questions for Pacific archaeology and other related disciplines.”

Fitzpatrick and his team, which includes Ohio State University geographer Alvaro Montenegro and University of Calgary archaeologist Richard Callaghan, offer some potential answers in a paper published Oct. 24 in the online early edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The paper, “Using Seafaring Simulations and ‘Shortest Hop’ Trajectories to Model the Prehistoric Colonization of Remote Oceania,” details the team’s use of computer simulations and climatic data to analyze ocean routes across the Pacific. The simulations take into account high-resolution data for winds, ocean currents, land distribution and precipitation.

“We synthesized a lot of new climatic data and ran a lot of new simulations that are exciting in terms of highlighting and pinpointing where some of these prehistoric populations might have come from,” Fitzpatrick said. “The simulation can assess, at any point in time, if somebody left point A, where would they end up if they drifted? We can also model directed voyages. If somebody knew where they were going, how long would it take them to get there?”

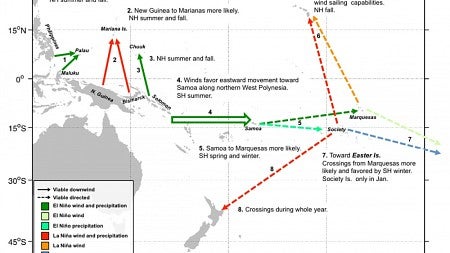

Fitzpatrick and his colleagues used their simulations to identify most likely ports of departure for the settlers of five major regions in Remote Oceania. To account for course variations due to wind and currents, the team created shortest-hop trajectories to assess the likely paths of least resistance. This technique factors in the role that distance and remoteness may have played in facilitating voyaging from one island to another and can include changes in sea level at different points in time that may have made these trips easier or harder.

Seafaring models have been developed and used by other researchers in the past, Fitzpatrick said, but they weren’t able to fully harness the high-resolution satellite data sets that have only recently been made available to scientists.

The research team’s simulations include El Nino Southern Oscillation patterns, which settlers most likely knew about and used to their advantage, Fitzpatrick said. Archaeological records reflect El Nino occurrences, which typically happen every three to seven years and can be seen in evidence marking droughts and fires. Because winds and associated precipitation shift from westerly to easterly during El Nino years, settlers would have found travel toward Remote Oceania more favorable when the pattern was occurring and may have timed their departures accordingly.

“What Pacific scholars have long surmised but never really been able to establish very well is that, through time, Pacific Islanders should have developed a great deal of knowledge of different climactic variations, different oscillations of wind and changes in environments that would have influenced their survivability and their abilities to go to certain places,” Fitzpatrick said.

The analysis provides insights about the origins of the early seafarers. The settlers of western Micronesia probably came from near the Maluku Islands, also known as the Spice Islands. Some of the team’s findings challenge current archaeological theories, while other data support existing lines of evidence. The research suggests Samoa was the most likely staging area for colonizing East Polynesia. It also indicates that Hawaii and New Zealand may have been settled from the Marquesas or Society Islands. Easter Island may have been settled from the Marquesas or Mangareva.

The new paper also highlights areas worthy of further research. It suggests that Samoa may have been an epicenter for colonization and challenges data that suggests the Philippines as a potential point of departure for the settlement of Micronesia.

The three team members brought complementary expertise to the study. Fitzpatrick contributed his knowledge of the archaeology of island and coastal regions in the Pacific and the Caribbean. Montenegro, the paper’s lead author, is a geographer and climatologist. Callaghan is an archaeologist specializing in seafaring simulations.

A question that may never be resolved is why seafaring settlers traveled such immense distances. Although evidence exists that some settlers were motivated by a desire to obtain new resources such as basalt or obsidian for making stone tools, Fitzpatrick said, there’s no easy way to explain the leap of faith it would take to set off on a colonizing mission of 400 to 2,500 miles.

“What drove the movement? That’s the big question," he said. "Was it political? Was it a result of population pressure? There were probably multiple reasons why people decided to leave one place and go to another.”

—By Lewis Taylor, University Communications