For some it means gratitude and togetherness, for some it means the opposite, and for some it just means feasting on turkey and football.

But, as recent conversations with two University of Oregon faculty members attest, the Thanksgiving holiday is also rich with history, folklore and social implications.

“Thanksgiving and other public holidays focus attention on some big questions in American history and political culture,” said Matthew Dennis, professor emeritus of history.

“At least for a day, the national past seems to matter, and historic events and heroes are recalled to teach us lessons about our origins, changing identity, values and principles,” he said. “Public holidays can help bind Americans together, or at least allow diverse Americans to claim a legitimate place in the nation, based, for example, on the inclusive message of Thanksgiving and its iconic immigrant story of the Pilgrims.”

According to Dennis, a specialist in early American history and author of “Red, White, and Blue Letter Days: An American Calendar,” the origins of the holiday are grounded in fact. What we generally think of as “The First Thanksgiving” was celebrated at Plymouth, Massachusetts, in fall 1621. The festivities stretched over three days, bringing together some 50 English colonists grateful to have survived their first year in America with about 90 native Wampanoag people.

“The original, now mythologized event actually emphasized inclusiveness, generosity, peace and cooperation among native people and newcomers,” Dennis said. “If subsequent American history had played out according to this model, the colonial history of America would have been much less bloody.”

Regrettably, Dennis noted, the rationale behind subsequent Thanksgiving celebrations would not always remain so benign.

“The Pilgrims’ English colonial neighbors, the Puritans of Massachusetts Bay, celebrated Thanksgivings to give thanks for good harvests and other benign events, but they also used them to mark native destruction and dispossession, as in 1637 after their massacre of hundreds of Pequots.”

Riki Saltzman, executive director of the Oregon Folklife Network at the UO and a lecturer in the folklore program, also writes and teaches about holiday traditions. She recalled that some of her students and colleagues, particularly those from indigenous cultural backgrounds, have continued to express fraught perspectives on the holiday.

“Most of us who grew up in American culture likely remember being taught the same lessons about Thanksgiving in school,” she said. “My daughter is now 20, and what she got in the school she attended in Iowa was akin to the lessons I got in my Delaware classroom years before. We learned about the Pilgrims, then drew turkeys by tracing five fingers and made headbands with feathers out of construction paper. It wasn’t culturally respectful, and we got a watered-down version of both the history and mythology surrounding this holiday.”

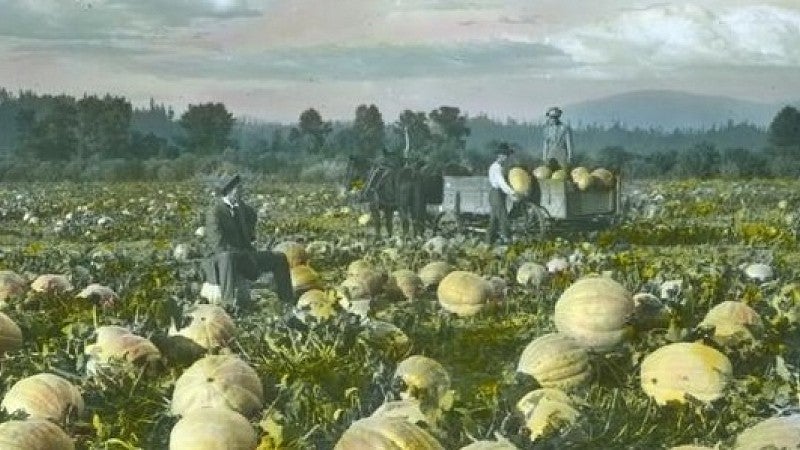

Although she believes many people continue to feel excluded during Thanksgiving, Saltzman also noted that there is a universal element embodied in the holiday’s agrarian origins.

“Most cultures have Thanksgiving-type holidays; they are harvest holidays,” she said. “An example from my own Jewish tradition: In the autumn we celebrate the harvest holiday, Sukkot. We build booths where meals are shared, we eat foods that make sense for the fall time and strangers are welcomed. Whatever your cultural tradition, all of our ancestors came out of an agricultural world, and so we have these remnants or survivals of ancient agricultural holidays. Over time, other origin stories accrue to them.”

In the United States, many of the mythologies took shape during the 19th century, as the holiday began to be thought of as a national event. Abraham Lincoln declared Thanksgiving a federal public holiday in 1863, during the Civil War.

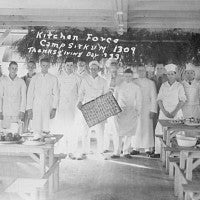

In the uneasy peacetime that followed, Thanksgiving played a role in narratives about national reconciliation, and as various immigrant groups came to the U.S. in subsequent decades, Thanksgiving was regarded as an important ritual in the process of assimilating new arrivals into American national life and culture.

Eventually, the day evolved into what Dennis calls “a great American paradox.”

“For a public holiday, Thanksgiving is quite private,” he said. “For a national holiday, it’s distinctively localized and variable. People accessorize their turkey meals with distinctive family and ethnic side dishes, treats Pilgrims never dreamed about. Often religious but not particularly sectarian, the Thanksgiving feast does not exclude non-Christians or nonbelievers. Though inwardly focused, Thanksgiving is also the time when Americans in the largest numbers reach out to the least fortunate in their communities.”

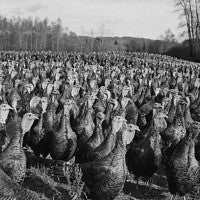

“If we were going to prepare a traditional meal that was reflective of the actual foodways of New England in the 17th century, then I suspect we all would be eating a lot more lobster on Thanksgiving,” she said. “Roast turkey was first popularized as part of the Christmas table in England. In fact, the so-called traditional Thanksgiving meal of today includes a number of items that only date to the post-World War II era of processed, packaged and fast foods. For example, according to my colleague Lucy Long’s research, ‘classic’ green bean casserole was invented and marketed by the Campbell’s soup company in 1955.”

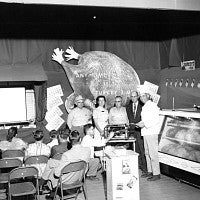

Saltzman said that food offers one of the best windows into all cultures, including our own. Furthermore, holidays centered on the preparing, sharing and consuming of food are a worldwide tradition. It is for these reasons, she believes, that Thanksgiving assumes some its special resonance in the pantheon of American celebrations.

“Although Thanksgiving is not precisely a traditional holiday, it has been a part of American culture for over 150 years, and that is time enough, I suppose, for it to have become a tradition,” she said.

Notwithstanding his observation that “American history is more complicated than the warm story of Thanksgiving,” Dennis reflected, “I think it’s significant that Americans have long celebrated the pluralistic, multicultural festival of Thanksgiving, centered on an immigration story.”

—By Jason Stone, University Communications