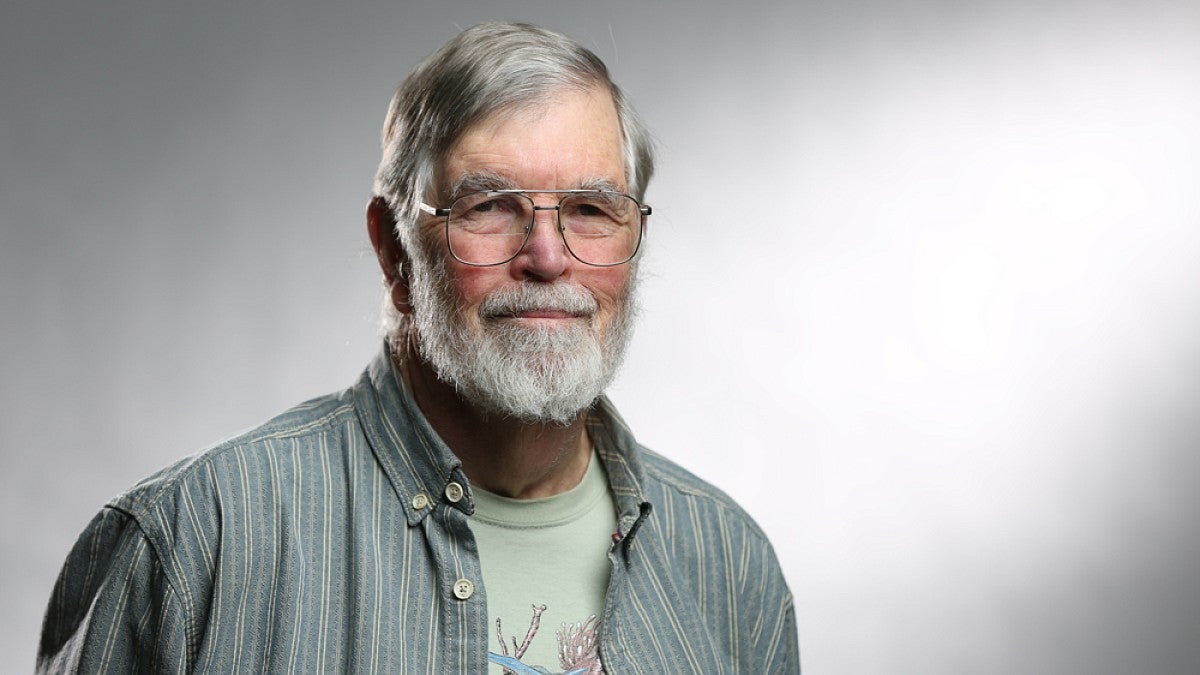

Chuck Kimmel, a UO professor emeritus in the Department of Biology and the Institute of Neuroscience, recently was honored for his contributions to the field with the International Zebrafish Society’s first-ever George Streisinger Award.

Streisinger, the late UO biologist, is widely considered the founding father of zebrafish research. Kimmel helped establish the foundation of modern zebrafish research.

“Without Chuck working very hard to promote the field, the whole enterprise could have just dwindled,” said Judith Eisen, a UO professor in the Department of Biology and the Institute of Neuroscience whose lab uses zebrafish to study neuron diversity during development. “It’s fair to say Chuck was absolutely instrumental in bringing us from where we were, with just a few labs at the UO, to where we are today, with well over 1,000 labs worldwide.”

Also receiving an International Zebrafish Society award was Adam Miller, an assistant professor in the UO Department of Biology and the Institute of Neuroscience, who was given the Chi-Bin Chien Award. The Chi-Bin Award recognizes young researchers who are emerging as future leaders in the zebrafish community, while the Streisinger Award recognizes senior researchers who have done “sustained and foundational work” and opened new possibilities within the zebrafish field.

“To get an award named for George is a special privilege,” Kimmel said. “George and I go way back and I feel very honored.”

Zebrafish research is now thoroughly ingrained in the culture at the UO, where about 100 researchers in 11 labs use zebrafish to study medical issues and answer fundamental questions about development. But that wasn’t always the case.

Kimmel said he was not thinking about zebrafish research when Streisinger recruited him to come to the UO in 1969. At the time, he was more interested in questions about biological specificity and was drawn to the UO by the Institute of Molecular Biology, one of the first interdisciplinary university research centers.

But by the late 1970s, Kimmel was working closely with Streisinger on several collaborative research projects involving zebrafish. Kimmel zeroed in on developing neurons in the zebrafish brain and embarked on a decade-long research quest to illuminate the developmental steps that led to different tissue types in the zebrafish embryo.

In 1984, Streisinger died while scuba diving. Kimmel and others who worked alongside Streisinger — including UO biologist Monte Westerfield and Streisinger’s assistant, Charline Walker — did their best to pick up where Streisinger left off and fill the void left by his sudden passing.

“George was a wizard of a person,” Kimmel said. “He was perfectly honest, perfectly brilliant, perfectly sharing. He just had a lot of positive attributes, which we all tried to emulate.”

At the time of Streisinger’s death, the zebrafish model was still struggling to find a foothold. With its fast development cycle and transparent eggs that form outside of the mother's body, the zebrafish provided a window on development and seemed to be a powerful model species for vertebrate developmental biologists. But within the scientific community, the question remained as to whether general biological insights could be made from studying a fish.

“I was worried that this whole field that he started was going to die,” Kimmel said.

Kimmel and his colleagues took over Streisinger’s grants and incomplete research projects, adopted his graduate students and continued to spread the gospel of zebrafish research to anyone who would listen.

Ultimately, through his tireless work as an evangelist for the zebrafish model, Kimmel helped rescue the field. His research helped place zebrafish in the context of vertebrate developmental biology and he succeeded in laying the groundwork for future generations of zebrafish researchers like Miller.

“George and Chuck are the reason that we all are here,” Miller said. “Chuck was so instrumental in everything that happened with zebrafish. He was critical and decisively smart about finding the right questions to tackle in the early days of zebrafish research.”

Miller’s award from the International Zebrafish Society was named after Chi-Bin Chien, a professor of neurobiology and anatomy at the University of Utah.

Miller came to the UO in December 2015. Years earlier, he studied in a zebrafish program directed by Chi-Bin at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachussets. He says the same spirit of generosity and openness that typified the work of Chi-Bin can be traced back to Streisinger and Kimmel.

Today Kimmel is a research-active 76-year-old whose lab examines the mechanisms that shape skull cartilages and bones during development. Kimmel is credited with characterizing many of the features of the early development of zebrafish and genetic mutations of the fish. Many of those early findings are still important today, but Kimmel says, it’s the people he worked with that he remembers most.

“Having such a mix of good people come through my lab who all have jobs all over the country and are department heads or are otherwise honored,” Kimmel said. “That’s a contribution that I’m really proud of.”

—By Lewis Taylor, University Communications