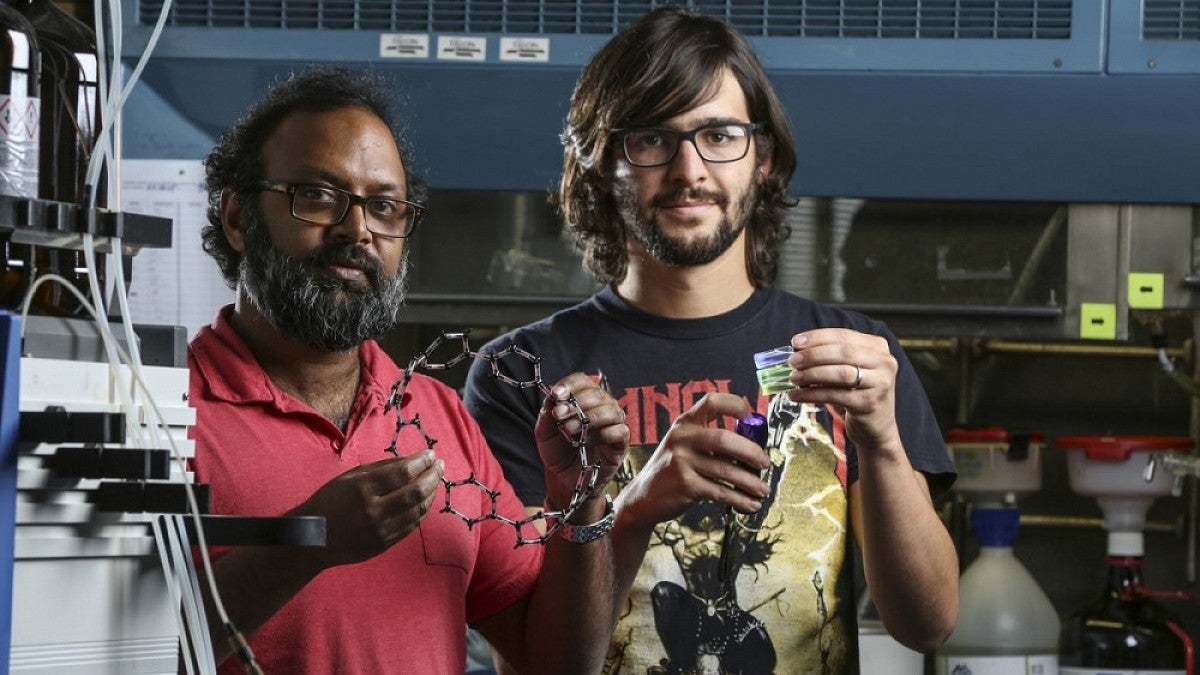

When Ramesh Jasti set out to make tiny organic circular structures using carbon atoms, the idea was to improve carbon nanotubes for use in electronics or optical devices. He quickly realized, however, that his technique might also roll solo.

In a new paper, Jasti and five UO colleagues show that his structures, which he calls nanohoops, can be made using both carbon and other atoms. Because they efficiently absorb and distribute energy, they may be useful in solar cells, organic light-emitting diodes or as new sensors or probes for medicine.

These nanohoops — smaller than the diameter of a human hair — are a new class of structures, said Jasti. He was the first scientist to synthesize them in 2008 as a postdoctoral fellow at the Molecular Foundry at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

"These structures add to the toolbox and provide a new way to make organic electronic materials," Jasti said. "Cyclic compounds can behave like they are hundreds of units long, like polymers, but be only six to eight units around. We show that by adding non-carbon atoms, we are able to move the optical and electronic properties around."

Nanohoops may help solve challenges related to materials with controllable band gaps — the energies that lie between valance and conduction bands and is vital for designing organic semiconductors.

"If you can control the band gap, then you can control the color of light that is emitted, for example," Jasti said. "In an electronic device, you also need to match the energy levels to the electrodes. In photovoltaics, the sunlight you want to capture has to match that gap to increase efficiency and enhance the ability to line up various components in optimal ways. These things all rely on the energy levels of the molecules."

To prove their approach could work, Darzi synthesized a variety of nanohoops using both carbon and nitrogen atoms to explore their behavior. "What we show is that the charged nitrogen makes a nanohoop an acceptor of electrons, and the other part becomes a donator of electrons," Jasti said.

Jasti, winner of a National Science Foundation Career Award in 2013, brought his research from Boston University to the UO's Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry in 2014.

(A longer version of this story is available, including the list of all the authors and funding supports.)

— By Jim Barlow, Public Affairs Communications