University of Oregon researcher Diego Melgar and a U.S. Geological Survey colleague were searching databases for information to feed a simulation of what a Cascadia earthquake would look like. Instead, they found a clue that points to the magnitude of an emerging megaquake.

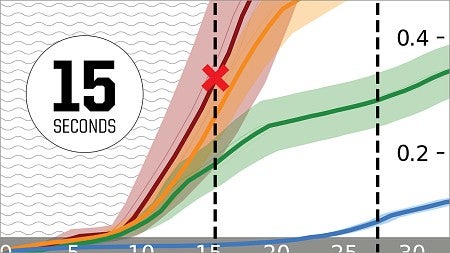

Reporting in Science Advances, Melgar and Gavin P. Hayes of the USGS National Earthquake Information Center in Colorado detailed a pattern in GPS data that emerges between 10 and 15 seconds into a quake. It’s the start of a slip pulse, a transition involving the acceleration of the separation, or displacement, of two plates. The peak rate of the displacement foretells whether an event will fizzle into a small quake or explode into a magnitude 7 or larger event.

“It was super exciting,” said Melgar, a professor in the Department of Earth Sciences. “As Gavin and I poured through the data for what were really unrelated reasons, we began to see these trends. We had a bit of a eureka moment where we, well, if what we’re seeing is true, it means something about how earthquakes start.”

The databases the researchers studied contain information from more than 3,000 earthquakes, with the same window of time indicating the severity of each event.

“The challenge is that we’ve found average patterns,” Melgar said. “Individual earthquakes have their own personality. There can be variability. A magnitude 9 can accelerate at different rates. We have to wait longer to be super sure about what we are seeing.”

The research was motivated by worries that the 620-mile-long Cascadia subduction zone off the Pacific Northwest coast, based on the fault’s history, is at risk for a full rupture that would generate a magnitude 9 earthquake. The last one occurred in January 1700. Melgar was seeking to model what the big one will look like.

GPS picks up initial movement along a fault similar to a seismometer detecting the smallest first moments of an earthquake. However, while GPS can detect displacement within centimeters along a fault line, the technology is not widely used in real-time hazard monitoring.

ShakeAlert, the West Coast earthquake early warning system that is being expanded to enhance advance notification in Oregon and Washington, does include land-based GPS stations in numerous locations, but the fault line itself is offshore where GPS stations cannot be used.

The Cascadia subduction zone is located where the Juan de Fuca ocean plate dips under the North American continental plate. The fault stretches just offshore from northern Vancouver Island to Cape Mendocino in Northern California.

“We can do a lot with GPS stations on land along the coasts of Oregon and Washington, but it comes with a delay,” Melgar said. “As an earthquake starts, it would take some time for information about the motion of the fault to reach coastal stations. That delay would impact when a warning could be issued. People on the coast would get no warning because they are in a blind zone.”

This delay could be reduced by placing sensors on the seafloor to record early acceleration behavior, he said.

—By Jim Barlow, University Communications