A little bird led Swedish-born Martin Stervander to the University of Oregon, but his journey wasn’t a direct flight.

As a doctoral student at Lund University he studied the genetics of a bird species that only lives on Inaccessible Island, a tiny patch of volcano-produced land in the Atlantic Ocean between South America and Africa.

While pursuing that research, he met UO biologist Bill Cresko and learned about a genomic analysis technology invented at the UO.

“I met Bill a few times, beginning at a workshop on the RAD-sequencing technology that he helped developed for his work in stickleback (fish),” Stervander said. “We immediately realized the potential of the technique and adopted it in several of our studies.”

RAD stands for restriction-site associated DNA. The methodology, which emerged from a collaboration between biology professor Eric Johnson’s lab and the Cresko lab, creates a detailed library of genetic code.

Last month, Stervander’s research took flight. He was lead author on a paper in Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution that identified the origin of Inaccessible Island’s bird, a rail. His team called for a reclassification of the flightless bird’s place in the avian tree of life.

The bird, according to its genetics, descends from a South American ancestor that also gave rise to the continental dot-winged crake. These sister species are related to black rails in the Americas and, probably, the Galapagos crake. Stervander recommends that the rail should be in the genus Laterallus to match its relatives.

The island’s bird was labeled Atlantisia rogersi in 1923, when British surgeon Percy Lowe, then head of the ornithology collections at the British Museum, first described it. He created the new genus, Atlantisia, in honor of mythical Atlantis. He also suggested that the rail may have walked to the island along a since sunken land bridge from either Africa or South America.

Plate tectonics later ruled out a land bridge, Stervander said.

“They flew or were assisted by floating debris,” he said. “Whether they flew all the way or were swept off by a storm and then landed on debris, we can’t say. In any case, they managed to make it from the mainland of South America to Inaccessible Island.”

More on Stervander’s discovery and the bird’s history is detailed in a news release “Researchers find the origin of an isolated bird species on South Atlantic island.”

Cresko met Stervander after traveling to Lund in 2012 to speak at a workshop arranged by the university’s research school in genomic ecology to discuss the RAD technology that had emerged from his and Johnson’s UO labs.

“This started a series of connections with the faculty at Lund University, as well as other places throughout Europe,” Cresko said. “I visited Lund several times subsequently and met with Martin to develop project ideas. I was impressed by his research and the questions he was asking.”

They jointly submitted postdoctoral proposals. The Swedish Research Council agreed to fund a three-year fellowship for Stervander at the UO.

“He’s here extending his research and getting experience working with fish models,” Cresko said. “He brings a depth of understanding of ecology and evolution but also a novel perspective from having asked research questions in birds. He also adds a fun international component to how our group thinks about science.”

Stervander’s interest in birds began as a child. Before entering Lund University, he worked in various research projects and as a bander in several bird observatories. For two years, he headed Sweden’s Ottenby Bird Observatory.

“I knew that I wanted to focus on the speciation of birds,” Stervander said. “I thematically asked, 'How does it work when a species evolves into two?' What are the mechanisms involved in that process? And can it happen even if the diverging lineages are not physically isolated from each other, like if they’re stuck on an island?”

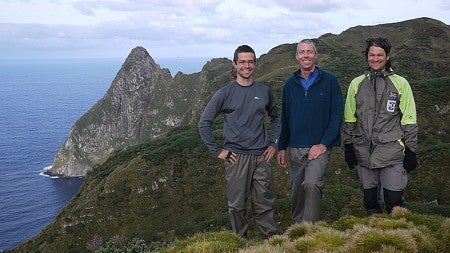

In addition to traveling to Inaccessible Island, he spent time on islands in the Gulf of Guinea off West Africa. He has a keen interest, he said, in finches that have colonized and evolved to survive on isolated islands.

In Cresko’s lab, Stervander is working with a family of fish that includes pipefish, seahorses and seadragons. All use their long snouts to suction their food. What he learns from the fish, he said, may help him understand how finches living in isolated locations have reshaped their bills to allow them to eat.

“I’d like to get closer to understanding the genetic underpinnings for the adaptation of their bills — their foraging apparatus — which happens in early embryonic development in preserved pathways,” he said. “How did this evolve, from finches to seahorse snouts? I want to find out how genes are turned on and off in the earliest developmental pathways in both the bird and these fish.”

—By Jim Barlow, University Communications