When Jon Bellona says listen to the ocean breathe, he’s not talking about the sounds of the surf. The senior instructor at the UO School of Music and Dance is referring to the cyclical exchange of carbon dioxide between air and sea.

For a three-year pilot project funded by the National Science Foundation, Bellona and a national team of researchers have transformed a year of carbon dioxide readings taken off the coast of New England into sound. Their audio exhibit is one of five case studies they created to help museums, aquariums and other informal learning environments make data more accessible.

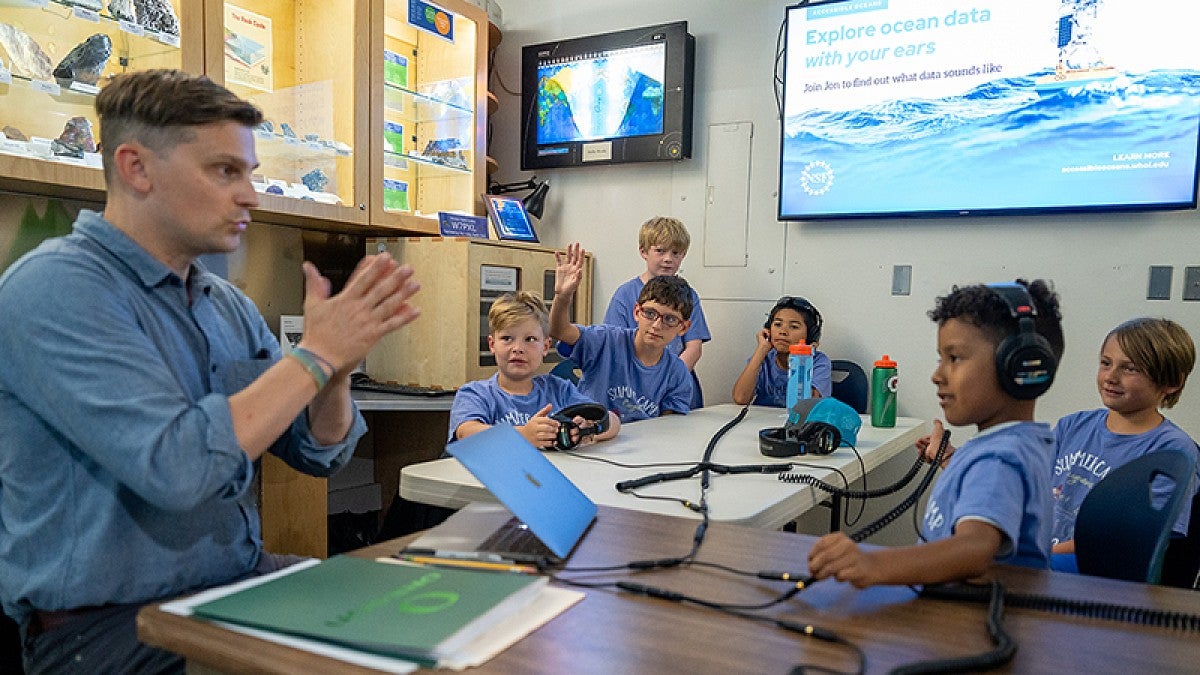

This July Bellona brought the project to the Eugene Science Center, where visitors had opportunities to take a listen. By observing their reactions and asking questions, Bellona got useful, real-time feedback — the kind of candid responses children are so good at providing.

For the sonic interpretation of carbon dioxide flux, Bellona made gas released from the ocean sound like wind that gets louder as the amount leaving the water increases. When carbon dioxide gets absorbed, it sounds like Jell-O being slurped.

Listening to both sounds at once offers insights into oceanography and climate change. The slurping option wasn’t his first choice, but Bellona went with it based on feedback from children and adults who are blind or have limited-vision.

In collaboration with researchers from across the U.S., Bellona is exploring how informal learning institutions can put sound to work through a process called sonification. A common example: The Geiger counter is one of the earliest sonification models that clicks at different speeds to indicate radiation levels.

Amy Bower, the principal investigator for the project titled “Accessible Oceans: Exploring Ocean Data Through Sound,” is an oceanographer who is legally blind. A senior scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Bower also works with the Perkins School for the Blind in Massachusetts.

Team member Jessica Roberts, an assistant professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology, is a specialist in learning sciences and interactive technologies. Leslie Smith is an oceanographer and science communicator in Tennessee who serves as executive director of Dive into the Ocean, Inc., an educational outreach organization.

“It’s been awesome to have all these experts from different fields,” Bellona said. “This interdisciplinary team has helped elevate the design and evaluation component, making our auditory displays more impactful out of the gate.”

Many science exhibits incorporate sound, Bellona said. But they’re limited to music, ambient noises or narration that enhances the experience without conveying quantitative information.

By sonifying discrete data sets that demonstrate scientific concepts — the research team calls these “data nuggets” — they hope to gain insights into what works for students and encourage science centers, aquariums and museums to add more sound exhibits.

Sonification makes learning more accessible for visitors who are blind or have low vision, helps promote data literacy, and reaches those who face challenges interpreting visual information. Bellona added that informal learning environments are designed to reach the general public and get kids excited about science, which makes their accessibility mission even more compelling.

Sonified data also can help scientists make new discoveries. For example, genetic researchers and astronomers use it to listen for patterns that can’t be seen in massive data sets.

In addition to the carbon dioxide flux example, Bellona has sonified data nuggets from an underwater volcanic eruption, Tropical Storm Hermine and zooplankton reacting to a solar eclipse. The research team solicited ideas from teachers and students at schools for the blind in Massachussets, Washington and Texas. They also conducted online surveys and are now testing their sound exhibits at informal learning facilities.

The feedback sessions included visits to the Atlanta Aquarium and the Eugene Science Center. Plans are underway for similar focus groups at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s Discovery Center and the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

All this feedback will reveal what works best for their target audience, Bellona said, helping the team develop educational design guidelines. After the pilot project, they hope to obtain additional funding and build a prototype sound exhibit.

—By Ed Dorsch, University Communications

—Top photo: Music instructor and researcher Jon Bellona get kids' reactions to sound-based data