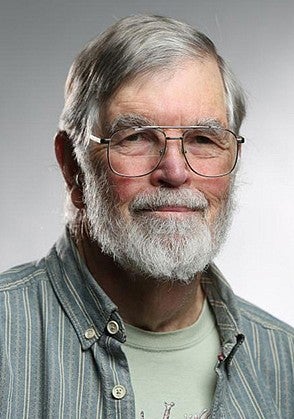

A species of tiny striped fish has allowed biologist Charles “Chuck” Kimmel to make a big impact on the understanding of vertebrate genetics and development.

For his scientific contributions, Kimmel recently was elected to the National Academy of Sciences, the most prestigious professional scientific organization in the U.S.

Kimmel, professor emeritus of biology at the University of Oregon, had big shoes to fill when he took over the zebrafish laboratory from George Streisinger, the first person to clone a vertebrate. When Kimmel and his colleagues in the Institute of Neuroscience took on that task, only a handful of labs were studying zebrafish.

And the UO’s facility and research labs have given rise to the Zebrafish International Resource Center, which breeds and supplies the fish for worldwide research, as well as the Zebrafish Information Network, where genetic and genomic data for the species is stored.

Using nearly transparent fish, Kimmel describes many long days and late nights in the lab with colleagues and students, watching how zebrafish cells treated with fluorescent dye divide in real time into daughter cells and how they move about. Kimmel’s tracing methods for cell lineage have been widely adopted by the research community.

“In those days it was almost a new paradigm of how to do biology,” Kimmel said. “To look in cellular detail at what’s going on and, with mutations, to learn how developmental genes function. When I was a student, we used tissue cultures when we wanted to observe living cells clearly.”

Later work with the model organism yielded insights into genes shared across vertebrates, which are animals with backbones. Genetic mutations present in zebrafish also could be identified in the corresponding genes of mice and humans. The discovery demonstrated that many basic patterning mechanisms are shared despite the diversity of body forms among vertebrates.

Beyond his work in cell lineage specification and movement, Kimmel also contributed to advances in the understanding of hindbrain segmentation and craniofacial patterning and evolution. He has been recognized by his peers as one of the leading developmental biologists working with any organism, having been previously elected president of the Society for Developmental Biology in 1993 and awarded the Conklin Medal for lifetime achievement in developmental biology in 2000.

When asked what he considers his greatest contribution, Kimmel’s response is simple: “It’s that I’ve trained some people who are doing really good work. Being able to contribute to the education of these great people was a super achievement.”

Kimmel lists Judith Eisen, Karen Guillemin, John Postlethwait and Monte Westerfield, who founded both the zebrafish resource center and database, as colleagues and collaborators who have been critical to the success of his research.

Kimmel joins 19 other researchers from the University of Oregon elected to the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine.

“Chuck’s groundbreaking work on developmental biology with zebrafish has not only been at the forefront of major advances to genetics research but also has taught us an incredible amount about how humans develop,” said Cass Moseley, interim vice president for research and innovation. “His election to the National Academy of Sciences demonstrates the impact the University of Oregon zebrafish research program, facility and data storage has had on the scientific community.”

—By Kelley Christensen, Office of the Vice President for Research and Innovation