Among the many wonders archived in the University of Oregon’s library and museum collections can be found a strange menagerie of monsters, ghosts and demons hailing from Japan.

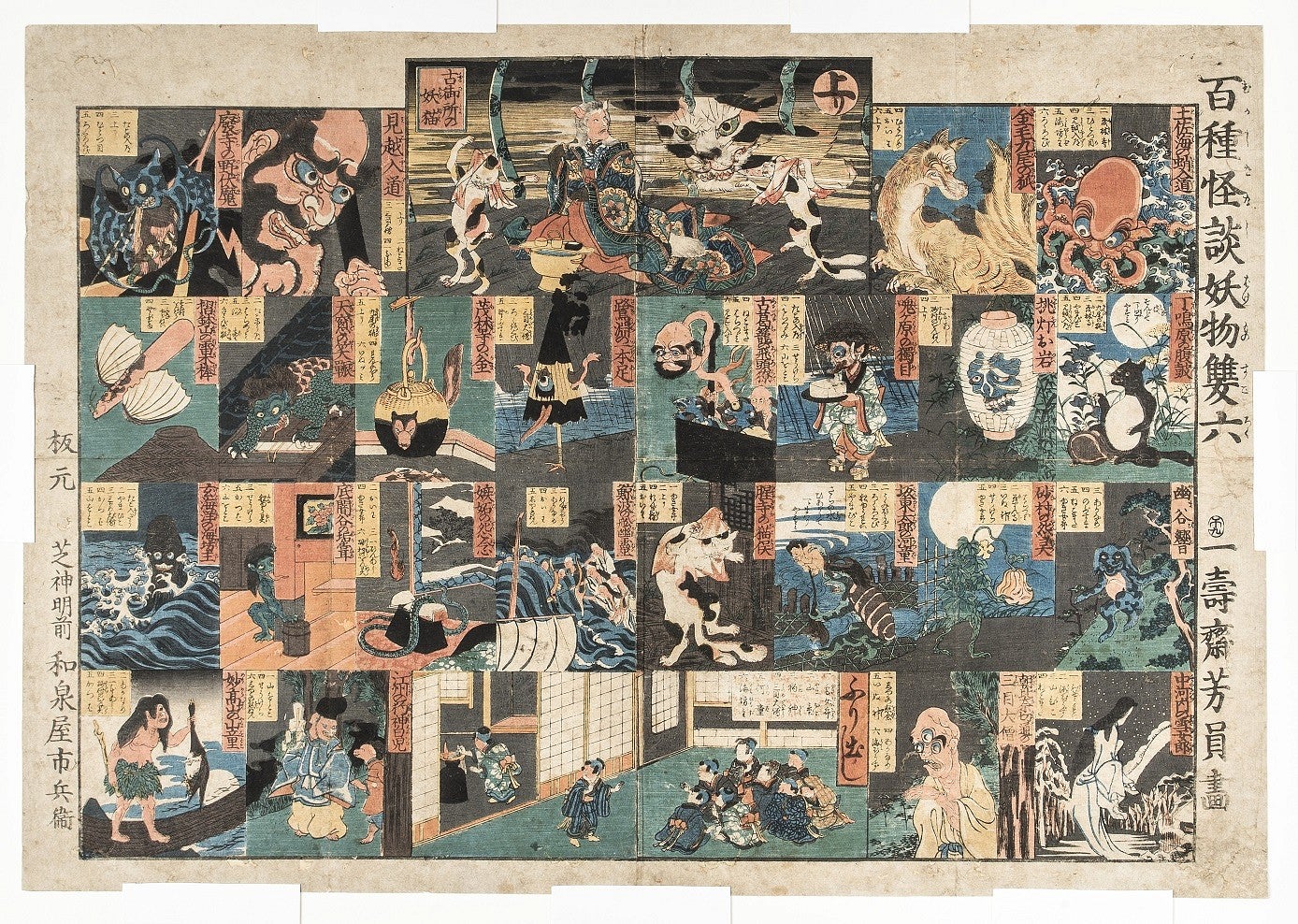

Known collectively as yōkai, these supernatural beings may look familiar to fans of contemporary Japanese media such as anime and manga. But the UO’s depictions predate motion pictures or graphic novels, and they are rendered on a scale that seems intended more to amuse the viewer than to frighten them.

“Probably the closest thing to compare them with now is trading cards,” said Glynne Walley, professor of East Asian languages, proffering a slip of ink-printed paper—a little bigger than a bookmark, it features a one-eyed, tongue-lolling monster holding a tray of tofu.

“It’s a collectable format intended for a subculture of people who are interested in the pictured themes.”

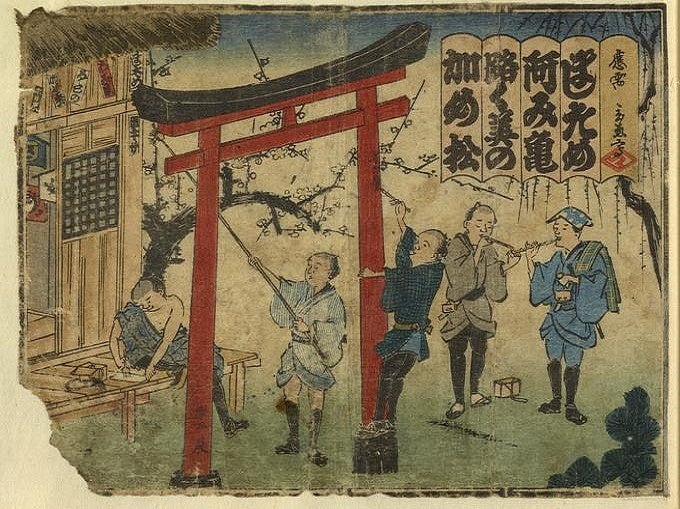

Known as senjafuda, or “thousand-shrine slips,” small woodblock prints like this were originally made by pilgrims in Japan to paste on the walls of temples and shrines as a kind of devotional graffiti. They later evolved into an early form of popular media that expressed endless thematic variations and inspired a devoted subculture of collectors.

According to Walley, the University of Oregon holds one of the world's finest collections. Encompassing materials held by the Special Collections and University Archives of the UO Libraries and the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, it consists of nearly a hundred scrapbooks filled with senjafuda plus several thousand additional unmounted slips. The earliest date to around the 1840s.

"These votive slips are miniature works of art with all the incredible craftsmanship and design sense we expect from Japanese art,” Walley said. "But what really interests me most is, they all contain writing. You can read more closely and learn so much more about the characters.”

An era of popular culture and popular creeps

Walley specializes in Japanese literature of the early modern period, which spans from 1603 to 1867 and is also known as the Edo or Tokugawa era. Popular mass culture in Japan has its beginnings here, and both yōkai monsters and senjafuda slips were among its abundant expressions.

Walley explained: “In the 18th and 19th centuries we see the emergence of woodblock printmaking technology and a publishing industry, which is nascent mass media. With it came what we can now recognize as a popular culture—that is, a culture whose products were supported by broad-based commercial sales rather than elite patronage. It played out on the printed page, in popular fiction, comic books and full-color prints.”

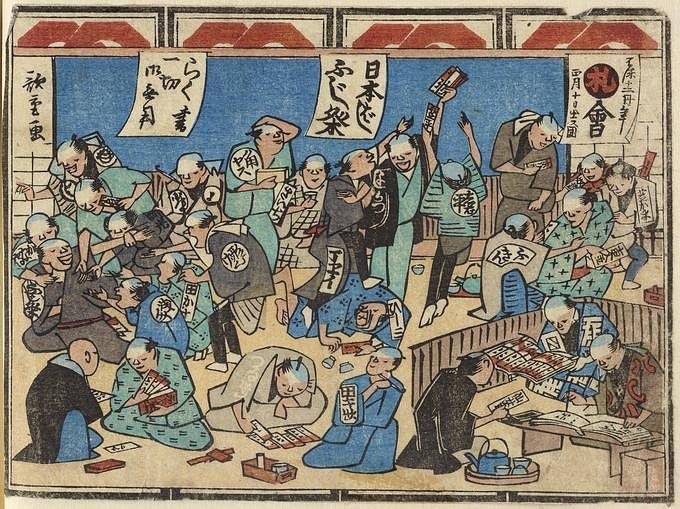

The senjafuda were another product of the printing block in this time of intense cultural foment. As their popularity grew, artistic themes expanded to encompass a huge diversity of subjects. By the 1830s, organized clubs of votive-slip aficianados were regularly meeting in restaurants and tea rooms to swap senjafuda and show off their vast collections.

Through the activities of exchange clubs like these the groundwork for the UO’s collection was laid. Between 1910 and 1925, Frederick Starr, a professor of anthropology with the University of Chicago, collected senjafuda on his frequent trips to Japan. Starr became such an engaged and well recognized figure in the collecting community that he was given the nickname O-fuda Hakushi, or “Professor of votive slips.” Following his death, Starr’s senjafuda collection was acquired by Gertrude Bass Warner, founder of the University of Oregon’s art museum.

“Even in Starr’s time, the senjafuda were embodiments of a powerful nostalgia for the way things used to be,” Walley said.

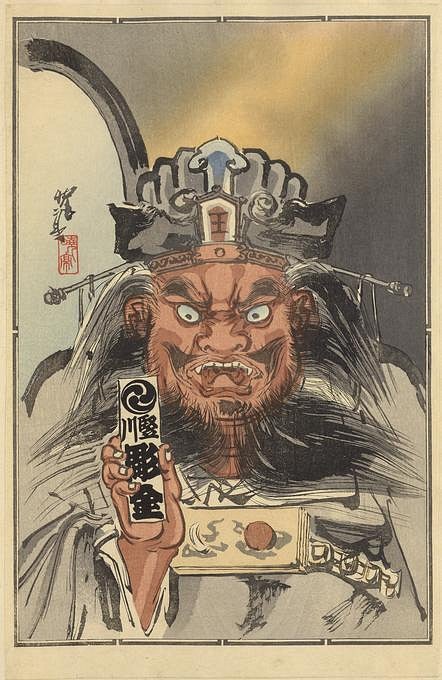

Like the temple-pasting slips, many of Japan’s monsters had pre-modern antecedents. Malign spirits such as King Enma, the red-faced ruler of hell, and the tengu, a beak-nosed creature associated with arrogance, feature prominently in medieval fiction and theater. However, it was the “floating world” culture of the Edo period that first imagined many of the islands’ supernatural beings. More traditional monsters also were refashioned to better fit the tastes and sensibilities of the era.

“So popular were depictions of yōkai in the early modern period, and so creative were those depictions, that they have indelibly colored later generations’ perceptions of these monsters. When you see yōkai today, they tend to be depicted in ways, and even wearing costumes, that date to the early modern period.”

Monsters that conquered the world meet the digital era

In the second half the 20th century, works like Mizuki Shigeru’s manga series “GeGeGe no Kitarō” and Studio Ghibli productions including the Academy Award-winning animated feature “Spirited Away” helped introduce Japan’s traditional ghosts and monsters to a global audience. Video games and card games also played a big role in promoting them far beyond their traditional homelands. One type of yōkai—a scaly, monkey-like creature called the kappa—even made a guest appearance in the Harry Potter books.

Given the enduring interest in these beasties, it is perhaps surprising that the UO’s yōkai-haunted collections are not better known to the public. Walley pointed to a practical explanation.

“They are awesome, but they don’t lend themselves well to museum exhibiting. If I wanted to create a museum exhibit, even assuming that people would have the patience to move through a huge room squinting at miniscule pieces of paper, it would be impossible for me to put everything together in context, because so much of our collection is mounted in different albums.”

Thankfully, recent developments in digital humanities scholarship and publishing have furnished a solution. With collaborators from the UO Libraries’ Digital Scholarship Services and Schnitzer Museum staff, and funding support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Walley recently produced Yōkai Senjafuda, a digital exhibition that deftly circumvents many of the inherent issues of size and locale.

“The scale of the original materials really lends itself well to the virtual space. With high-resolution scans served digitally, you can zoom way in—close enough to see the grain of the paper and the way the ink seeps in. You can examine it much more carefully than the original version.”

The site was created in Omeka S, the latest version of the leading open source web publishing platform used by museums, libraries and archives to publish their collections and develop narrative exhibits. According to Franny Gaede, head of digital scholarship services with the UO Libraries, Yōkai Senjafuda was among the first projects in the world to be published using the new platform.

“For us, this was a chance to innovate,” she said. “A lot of the work we did and feedback we provided actually led to changes that were integrated into the 2.0 version of Omeka S. Our UO team helped create themes and plugins that people all around the world are going to be able to take advantage of.”

Walley estimated that his own investment of time in curating the site exceeded two hundred hours.

“I didn’t envision it as a book project, but at the end, when I totaled up the number of words I had written, I realized that I had basically written a book! But it was the most fun ‘book’ I’ve ever written. It’s a different kind of writing. And in this day and age, we can achieve a much broader audience reach with a website than with a book.”

Visit Yōkai Senjafuda and Oregon Digital to learn more

Featuring a browsable gallery of 314 art images and text by Glynne Walley, professor of East Asian languages, the digital exhibition "Yōkai Senjafuda" was developed with support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Oregon Digital collections are comprised of unique digitized and born-digital materials created to support the teaching and research missions. Oregon Digital is collaboratively managed by the UO Libraries and OSU Libraries.