‘Field Guide’ to flourishing: student mural provides catharsis, connection

Anthony Ryder invites viewers to enjoy natural wonders all around the UO in birds, plants and waterways

Micah Evans runs in Alton Baker Park, and it felt like a day on the trail recently when the University Housing employee came across a mural going up in Justice Bean Hall: Autzen Stadium depicted in one corner, the Willamette River nearby, native camas bulbs and, of course, lots of ducks. A classic University of Oregon landscape.

But one thing stood out — a peak resembling Japan’s Mount Fuji. Wouldn’t one of Eugene’s popular buttes be a better fit? Evans suggested as much to the organizers of the mural project . . . and was excited to learn soon after that the artist would readily incorporate his idea.

Many artists seek to connect, on some level, with their audiences. But for nontraditional student Anthony Michael Ryder, connection isn’t just the goal of his art. It’s what drives him in life.

Ryder is one of five student artists in Flourishing by Art, a new art initiative that supports the university’s strategic goal of helping everyone at the UO to flourish. Under the joint project of Housing Capital Construction and the Associated Students of the University of Oregon, Ryder and the other artists recently completed the aforementioned mural, two others and a sculpture for three residence halls.

Key to the university’s flourishing goal is creating robust connections between students, staff and faculty. The art initiative fosters those connections: nearly a dozen units at the UO came together to launch the project quickly over the summer and, through art, the student artists are connecting with peers and others across the university.

For Ryder, a 28-year-old senior and art major, those connections are nothing short of therapeutic.

Ryder lost his mother, Arenda Lee McCulla, to breast cancer in 2021, at age 47. It left him reeling; he felt alone with the hurt and isolated from the world around him. The prospect of going even to the supermarket seemed overwhelming.

But art can help with recovering from grief and other trauma, according to Lisa Abia-Smith, a senior instructor in the School of Planning, Public Policy and Management. She is the director of education at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, where she leads Art Heals, a well-being program.

With even 20 minutes of art making, cortisol levels drop and the heart rate slows, Abia-Smith said. “That act of slowing down, using your hands, being present with yourself — there is a serenity that happens. When you have a death or grief or trauma, art is a way to navigate that experience.”

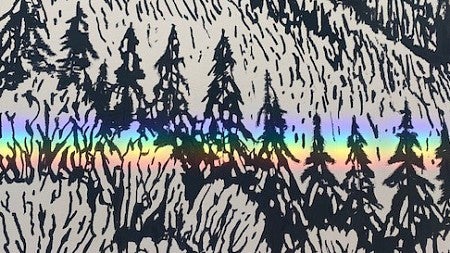

Ryder’s black-and-white mural for Justice Bean Hall, “Field Guide,” isn’t overtly personal in subject matter. But it is personal — it’s the latest undertaking by an accomplished artist whose pieces provide catharsis and connection.

“It’s a grief journey,” said Ryder, who used paintbrushes provided by his mother and kept her memory close while doing the work. “It’s a big connection point not only to her but to other people. Sometimes with trauma it can make you callous towards the world to protect yourself. But [art] forces that curiosity to reconnect with people, to figure out what they experience in a piece. For me, it’s always been about connection.”

In much of his work, Ryder uses various mediums to explore themes of trauma, vulnerability and indigeneity (He is Ojibwe, with paternal roots and family based in the Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians reservation of Ste. Marie, in Michigan’s eastern Upper Peninsula.) He has participated in more than 30 group exhibitions nationally and internationally, including “Many Americas,” a national show funded by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Arts in 2022 that examined the country’s divergent histories and troubled civic discourse.

For that show, Ryder created a contemporary dream catcher with historical and family photographs to explore bodily trauma and the displacement of native people. “He gets close to the bone,” said CoCo Harris, a friend and fellow participant in the exhibit. “When you get personal and you put bits of yourself in your work of art, it has a different resonance. And he’s gifted — I tell him that and he just laughs, but he’s brilliant.”

Those who know Ryder at the UO say he is a student who distinguishes himself through an unwavering commitment to education and deep engagement with those around him.

Brian Gillis and Michael Rey, faculty in the School of Art + Design, said Ryder has consistently gone above and beyond coursework expectations and shown a curiosity for all aspects of art that makes him a joy to teach.

“A bond that we share comes from something rooted in gratitude and acknowledgment of the chance to live life,” Gillis said. “He legitimately appreciates human interaction, appreciates the opportunity to get an education. It’s really been inspiring to me to be in his orbit.”

That sentiment was echoed by Kirby Brown, an associate professor of Native American and Indigenous literary and cultural production in the College of Arts and Sciences.

Whether guiding his classmates through an exploration of Indigenous short film or volunteering at the Many Nations Longhouse for programs such as the Mother’s Day Powwow, Ryder lifts those around him, Brown said — but always with genuine humility.

“Anthony is, in many ways, a classically Indigenous leader,” Brown said. “That’s a kind of leadership where you lead from the rear and you elevate other people. It’s not about being the person in front who speaks for everybody, it’s about being the person in the back who’s pushing everybody else forward.”

Ryder’s sincere interest in other’s lives can catch them off guard, but there is a richness in making those connections, added recent graduate Katarina Allison, a close friend of Ryder’s through the Longhouse.

“Life is more interesting that way,” she said. “You can connect with people on a deeper level and appreciate more empathy and compassion.”

As Ryder was working on the mural one day over the summer, he was struck by a happy occurrence: sunlight from a window was being refracted on the wall, adding a rainbow that moved across his landscape. He shared the effect with project coordinator Lillian Moses, director of Housing Capital Construction, bringing a smile to her face.

“I’m so glad Anthony has enjoyed the space and connections with folks,” Moses said. “That is the kind of human connection we hoped art would support.”

Ahead: Flourishing by Art student profiles

The Workplace e-newsletter — emailed Tuesdays to staff and faculty — will feature the student artists of Flourishing by Art in the weeks ahead.

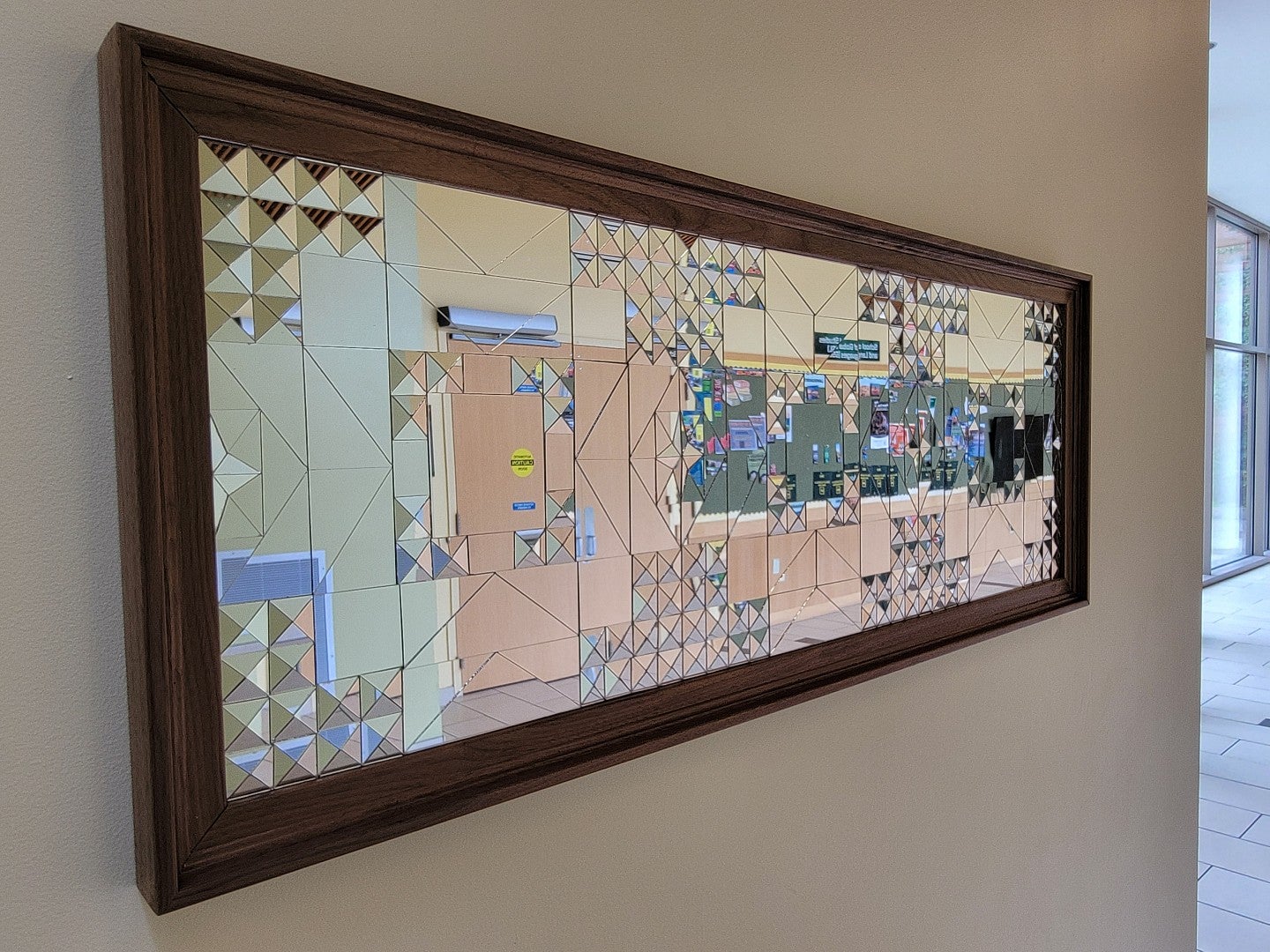

Oct. 14: Emerging artists need venues. Flourishing by Art provides one for Parisa Garazhian, an international student who combines Iranian mirror work and American quilt-making into a literal reflection on identity.

Oct. 21: Lucy Rutherford (black-and-white T-shirt) and Dani Jacobs have been friends and artists since middle school. They brought divergent artistic approaches to their first major collaboration.

Oct. 28: Decorative painter Stella Prichard is driven to create — and to critique her creations. Her mural was the latest step on a path of learning to trust her decisions as an artist. (credit: tucker.grt@icloud.com)

See Flourishing by Art

Faculty, staff, students and the general public can view students’ works.

“Flora and Fauna”: Global Scholars Hall, mezzanine, 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday through Friday during the academic year, excluding breaks.

“Mirror Quilt”: Global Scholars Hall, first floor, 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday through Friday during the academic year, excluding breaks.

“Two Birds, One Stone”: Living Learning Center South, west hall, first floor, 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. weekdays and noon to 7 p.m. weekends during the academic year, excluding breaks.