Every summer, students and faculty members from the University of Oregon travel to the Museum of Natural and Cultural History’s Archaeology Field Schools.

Working and learning in remote desert regions of central Oregon, they spend six weeks uncovering evidence of the earliest known people in North America.

Field school is on-the-ground archaeological training, and that means there's lots of digging. But beyond just getting their hands dirty, students learn how to read topographical maps, conduct pedestrian surveys, and write up field reports—all crucial skills in the discipline and profession of archaeology.

The UO has been a leader in the field since the 1930s, when faculty member Luther Cressman began his trailblazing archaeological work in Oregon. His excavations found evidence that significantly pushed back western science's understanding of the time scale of humans' arrival in North America. Today's field school students, researchers, and faculty members gain direct experience while carrying forward this important work.

Dawn Breaks

The sun rises over the desert hills of Fort Rock Basin in the “Oregon Outback.”

It's 5:30 a.m. and the earliest risers in the group, including field school director Dennis Jenkins, begin leaving their tents to congregate and brew coffee for the camp. Several coffee pots set to percolating, jockeying for space and electricity in a yurt that serves as the camp’s kitchen.

“I make sure to wish everyone a good morning and let them know we’ll be having a good day doing something really important,” says Jenkins, a specialist in archaeology of the Great Basin region.

Dennis Jenkins, a.k.a. “Dr. Poop,” is a senior research archaeologist and former director of the UO's Connley Caves Field School.

Jenkins' unusual nickname comes from his extensive work with coprolites, or fossilized feces. His research in Oregon's Paisley Caves confirmed that humans were living in the Great Basin thousands of years before the Clovis peoples, who were long thought to have been the first people in North America.

Jenkins will retire this year after more than 30 years leading the field school. In collaboration with two colleagues from the UO, he literally wrote the book on Oregon Archaeology.

Assistant Professor of Anthropology Katelyn McDonough has been co-director of the Connley Caves Field School since 2019.

She had a life-changing field school experience as an undergrad at the UO in 2011, then went on to earn her Ph.D. from Texas A&M's Center for the Study of the First Americans. McDonough's area of expertise is the diet of people living in the Great Basin.

“We’re focused on getting a holistic view of life here,” she says. “Understanding perspectives from Indigenous people and involving local Tribal communities is really important. It's vital to understand what’s important for the people whose homelands and heritage this is.”

Alongside field school students from the UO, their peers from the University of Nevada, Reno, the University of Utah, and the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs are also slowly waking up.

As other archaeologists rise, field school director Katelyn McDonough, an assistant professor of anthorpology with the UO, and field director Richie Rosencrance get out lunch supplies and breakfast fixings. If it’s a special day, Rosencrance might cook up a hot breakfast, complete with eggs, bacon, sausage, and more coffee.

Everyone packs a lunch for the noon lunch break, fills their water bottles, and eats a breakfast that will sustain them for several hours of hard, physical labor. Everyone contributes to the camp in some way, whether it’s packing the vans, putting the lunch supplies away, or filling the communal water jugs.

At 7:00 a.m. sharp, McDonough calls the morning meeting to order. Together, McDonough and Jenkins have more than 50 years of experience in Oregon archaeology, and they emphasize the importance of building a team.

Everyone discusses the plan for the day. The meeting agenda includes camp news—such as expected outside visitors or upcoming port-a-potty maintenance—as well as what the team can expect at the site.

Once the meeting is adjourned, all hands scramble to the vans and trucks. It's time to start the day.

Excavations in Connley Caves extended to a depth of several feet.

Field school students and staff show their spirit in Connley Cave 6.

A Day at the Caves

A series of eight caves, Connley Caves offer a unique view into life in the late Pleistocene.

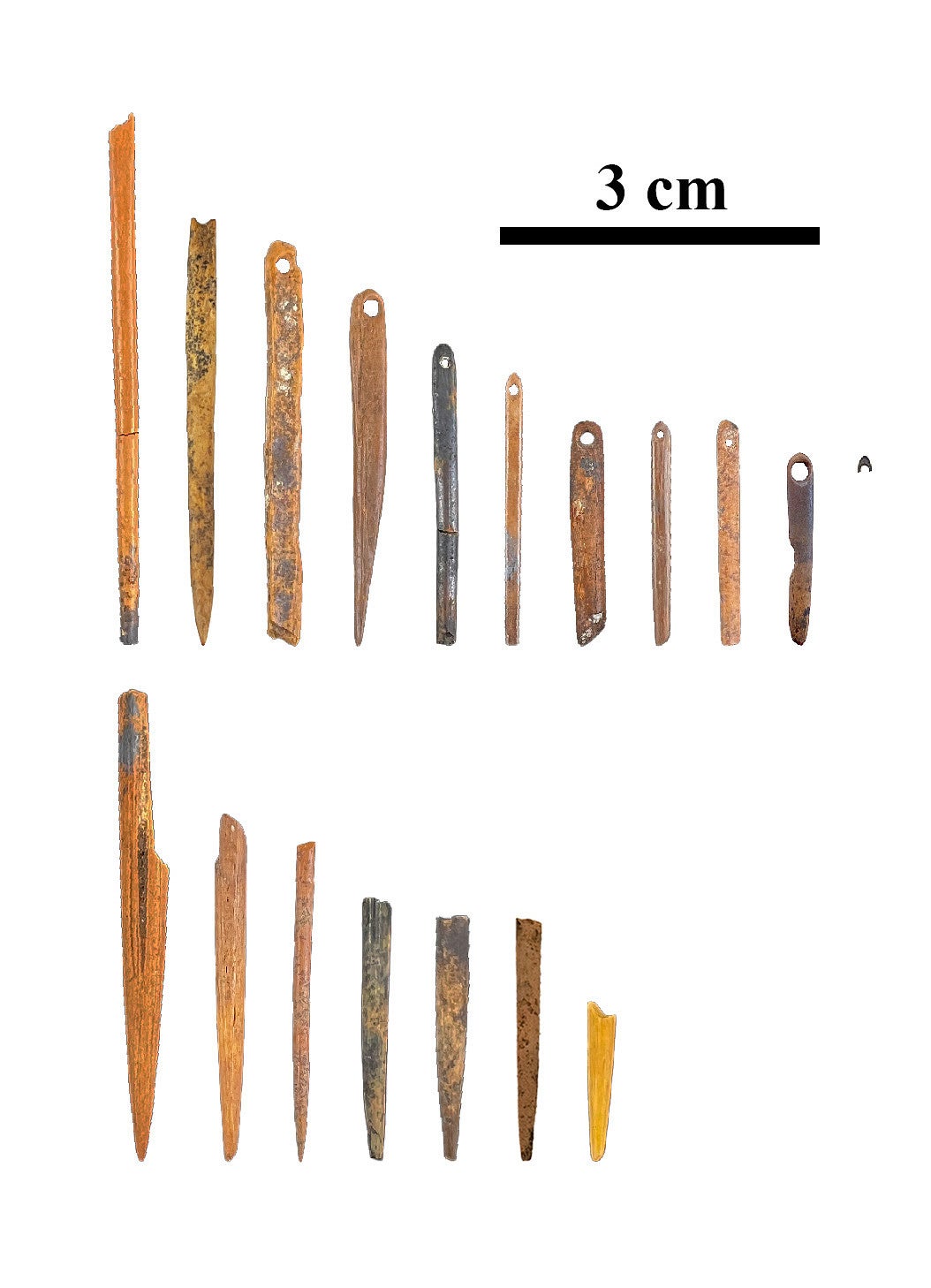

About 13,000 years ago, when large lakes dotted the Great Basin from Central Oregon to Southern Nevada, abundant fresh water sources created sustainable ecosystems of edible plants and animals. For thousands of years, people lived in the area and spent significant time in the caves. Thanks to the protection from the cave walls and central Oregon’s arid environment, material objects from their lives remain intact today, from bone tools to sagebrush cordage.

This is the first year the UO Museum of Natural and Cultural History's Connley Caves Field School has partnered with Geoffrey Smith from the University of Nevada, Reno to teach field school, though the two institutions have a long history of research collaboration. Many field school attendees are students of anthropology, but the field school focuses on interdisciplinary research, as Connley Caves has become a hot spot for experts in a variety of fields such as geoarchaeology and paleobotany.

Each field school student gets assigned a one-square-meter area that they meticulously dig, little by little, for the entire six-week session. Using trowels and brushes to sweep dirt into dust pans, they look closely for evidence of human life, including charcoal from hearths, animal bones, stone tools, coprolites, and debitage, the pieces of stone that flake off during the knapping process.

Kelby Beyer, Class of ’24

Aiden Hlebechuk, Class of ’23

Bianca Owens, Class of ’23

Riley McCormick, Class of ’22

Sonya Sobel, Class of ’18

Matt Skeels, Class of ’23

Figure 1: A selection of bone needles found in

the Great Basin. Courtesy Richie Rosencrance.

Currently pursuing a graduate degree in anthropology with the University of Washington, UO grad Sonya Sobel '18 also has eighteen months of professional background working for the Museum of Natural and Cultural History as a researcher in cultural resource management archaeology. Even with that experience, she says, field school has opened up a new world of possibilities.

“I was able to learn how other people excavate. Even just understanding other people’s techniques for holding their trowels and moving the dirt was really beneficial.”

Another student, senior Aiden Hlebechuck, plans to become a professional archaeologist and is already in the Museum of Natural and Cultural History’s pool of research assistants.

“It’s one thing to sit in a lecture hall, or, in my case, a PowerPoint on a screen [due to COVID distance learning], and learn the principles of archaeology,” he reflects. “But to actually be in the field and do archaeology is an entirely different feeling. The two are not the same.”

The UO's Museum of Natural and Cultural History has maintained an active program of field research in archaeology since 1937.

Today, our field schools offer graduate and undergraduate students practical training in excavation techniques at two of North America's earliest cultural sites.

Coming to a Close

At 3:30 p.m., after a long day of excavation or survey, it’s time to return to camp. The evening is their own to do with what they will, other than camp chores. One UO student, Matt Skeels, often pulls out a guitar before dinner, adding to the soundscape of camp life. The people cooking dinner get dibs on the few shower stalls—the campsite has running water but no indoor plumbing, so students leave sun showers out all day to warm up.

Over the course of six weeks, visiting scholars and experts lead discussions and hands-on demonstrations. One of North America’s top flint knappers stopped by to give students some hands-on training on creating their own stone tools. Diane Teeman, Cultural and Heritage Director of the Burns Paiute Tribe, spoke to the field school about her work and the intersections of archaeological research and Indigenous understanding. One evening, Sobel challenged everyone to an atlatl throwing contest. (Wait . . . What’s an atlatl?)

Building a community is about more than just comradery.

“We need to bring individuals together, as quickly as possible,” Jenkins said. “Some are in their 60s, some are 18 years old. You have people from all different backgrounds and walks of life. It’s our job to get them to function together as a team.”

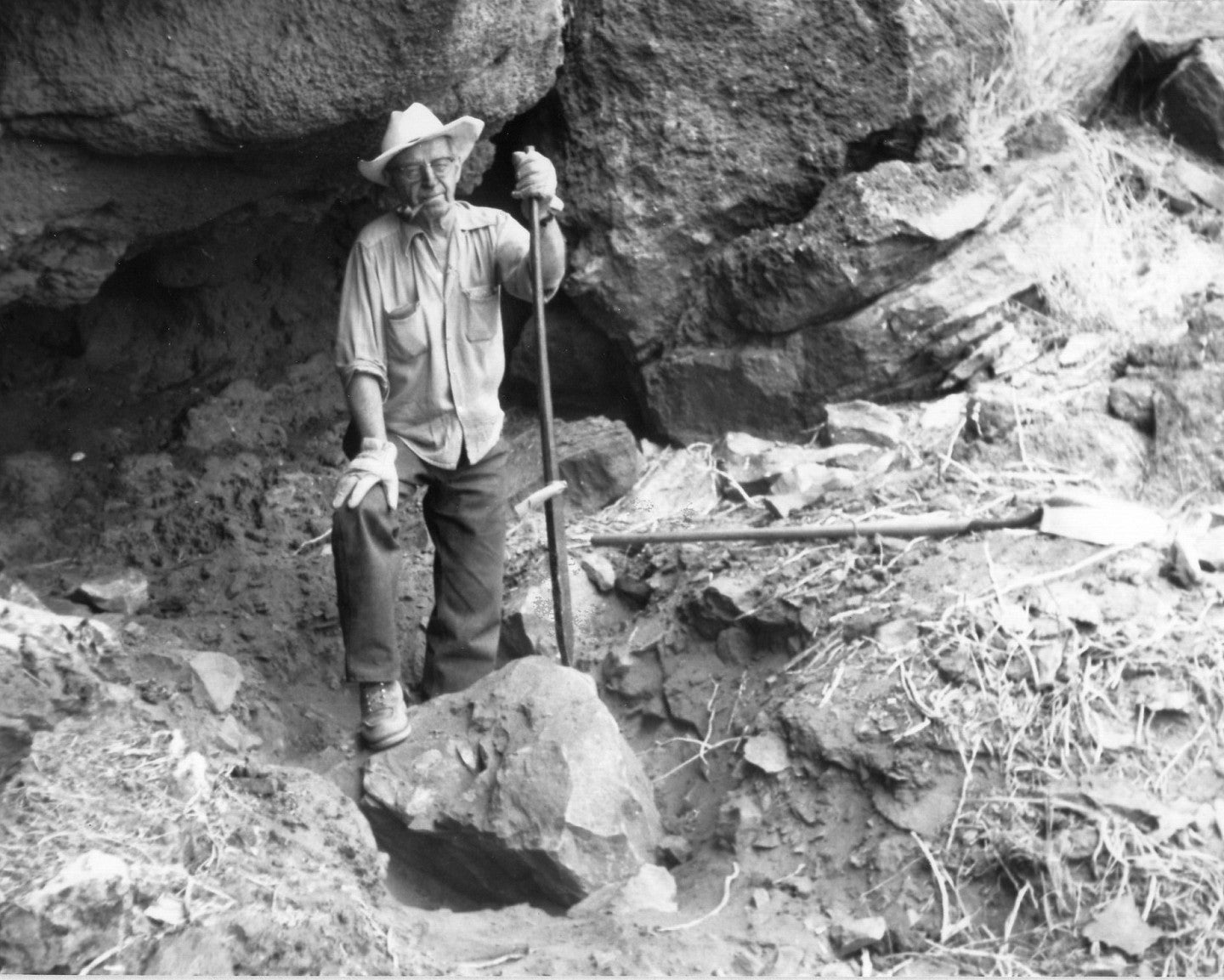

Luther Cressman (1887-1994) was a professor of anthropology and founder of the Museum of Natural and Cultural History at the University of Oregon.

A specialist in pre-contact archaeology, Cressman's groundbreaking work at Fort Rock Cave and Paisley Caves in the Northern Great Basin would significantly recalibrate the known scale of time for human habitation in North America.

He was also a pioneering documentary filmmaker. A priceless historical resource now preserved by the museum, Cressman's films captured decades of field work throughout Oregon.

The community they built together was everyone’s favorite part.

“This was my first experience working in a professional setting with a team,” Beyer said. “It could not have gone any better.”

“I got pretty close to the other students,” said Bianca Owens, who will return to Eugene as a senior this fall. “We built a little community out there for six weeks, and it felt great to be a part of that team.”

Years later, Jenkins reflects, former students still reach out to tell him, ‘That summer changed my life.’

“They learn responsibility, teamwork. For many, it’s their first time working eight hours a day, let alone outside. If you can get through this, you’re an archaeologist.”

19

84

50%+

Previous Stories