Combating Racism

March 2022

At the UO, as across the country, we have had to face a renewed reckoning around issues of race and inequality. We know the work of creating a more inclusive and antiracist community is a continuous journey. Each month, these pages will highlight some of the work being done and the resources available here on campus. We hope these efforts act not as a token, but as a turnkey to help open doors for those to come.

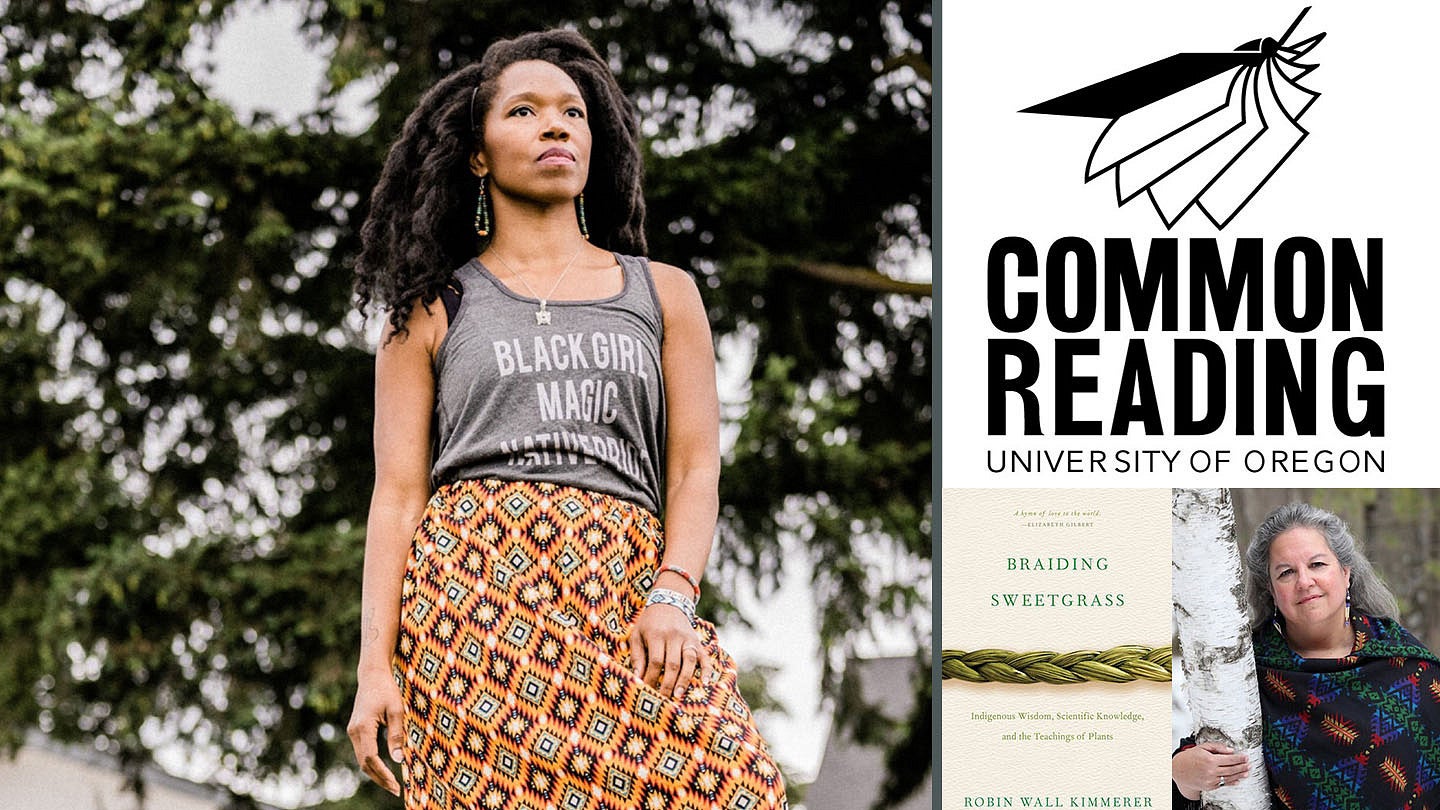

Amber Starks, striving for a decolonial future

Having experienced oppression both as a Black and Native person, the alumna activist and community organizer—in residence with Common Reading—is impressing upon UO students the need to translate ideas into practice.

By Anna Nguyen

Photo of Amber Starks by Josué Rivas

Amber Starks wants to grow the idea of a new future—by planting the seeds of resistance today.

Starks, BS ’03 (general science), returned to the university in residency with the Common Reading program this year. Her work expands the conversations generated by this year’s Common Reading selection, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer, while engaging with diverse stakeholders in the campus community.

Starks’ relationship to her Black and Native identities is critical to her work. By habitually immersing herself into spaces of struggle, learning and growth, Starks has been able to explore the parameters of her Blackness while deepening her connections to her Muscogee roots in Oklahoma.

“I want people to listen to us and center our voices and conversations,” says Starks. “This residency was meant to highlight the work that Afro-descendant and Indigenous people have been doing in Eugene, Springfield, and Oregon.”

As an Afro Indigenous activist and community organizer, Starks grounds her work in the rich and complex experiences of Black and Native Americans. She explored these connections with ethnic studies professor Brian Klopotek last spring in a course framed around Black and Native relationality.

Says Starks: “Afro-descendant and Indigenous peoples are the architects and authors of our liberation, our freedom, and our sovereignty. The work that we are doing today is a continuation of the work our ancestors have been doing to make that history and legacy visible.”

Through her commitment to community work across departments and programs, Starks seeks to contribute to the groundwork and foundations for stronger relationships between faculty members, students, and staff, which have been laid out by those she considers her forbearers and contemporaries.

She participated in a keynote conversation with social anthropologist Irma Alicia Velásquez Nimatuj at the Air, Water, Land symposium last November. Hosted by the Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies, this event served as a point of discourse for Black and Indigenous scholars and environmental justice activists.

One important aspect of Starks’ activism is her commitment to solidarity building. Having experienced oppression both as a Black and Native person, Starks is driven to cultivate connections between and beyond both communities. To Starks, these connections are crucial in the broader fight against white supremacy, settler colonialism, and anti-Blackness on a global scale.

Since graduating from the University of Oregon, Starks has participated in a multitude of advocacy efforts in Portland and beyond. After spending a few years in the nonprofit sector, Starks led a campaign around HB3409, which changed licensing restrictions for natural hair stylists. She then started Conscious Coils, a natural hair salon that is oriented around traditional and contemporary African and African American hair care.

These achievements speak to the value of Starks’ vision as one that affirms global Black liberation and Indigenous sovereignty, particularly as “acts of refusal, resistance, futurity, and ‘thrivance’.”

This year’s Common Reading selection, Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, reflects on the complex and reciprocal relationships between humans and the more than human world. Students, faculty, and staff are provided with opportunities for engagement with the text and its author on campus and beyond. Starks has played a key role in several of these projects over the past few months.

“Amber’s engagement with UO Common Reading’s Unceded Kinship: Land Place People project has been boundless,” says Julie Voelker-Morris, director of UO Common Reading. “She is now developing an exhibition of Afro-descendent and Indigenous identified contemporary artists at the UO and beyond.”

“We need to practice what we say we want, in the midst of our oppression”

Starks’ involvement in the Common Reading program emphasizes the importance of translating Black liberation and Indigenous sovereignty from theory into practice. She sees this long-term struggle as a journey punctuated by moments of unity, conflict, and everything in between.

“We need to practice what we say we want, in the midst of our oppression,” she says. “When we get free, my fear is that we’re going to replicate systems that we say we don’t want. This community work, for me, is what we’re practicing and putting into reality.”

Starks believes that, with the right intentions, universities can play a key part in shaping the trajectory of an antiracist and decolonial future. Academic institutions should be amplifying and supporting the efforts of students and community members, she says. Campus-wide initiatives for racial justice are connected to the work done by generations of Black and Native students, and the foundations they laid for future advocacy efforts.

To Starks, universities tend to react to harm done after these actions have happened. Being proactive with their diversity, equity, and inclusion work means they must relinquish the power they have as an institution to meet the needs of the community.

“I don’t trust institutions to be genuine about change if they themselves don’t already have a long-term goal for how they are going to deliver it,” Starks says. “If a university is genuinely concerned about racial capitalism, patriarchy, and other systems of oppression, the administration needs to work with the community to listen and come up with plans for how to address it. This means that there’s going to be a lot of cross-cultural communication, which is difficult, but I don’t think universities are strangers to hard work.”

Resources

Visit these resources—a small sampling of the many on campus—for ways to listen, learn, and act in the fight for social justice