Brother of baseball icon Jackie Robinson. Silver medalist behind Jesse Owens. Considered inferior in his own country. But Mack Robinson was a born winner whose legacy continues to this day.

Adolf Hitler’s hatred of Jews and Black people meant Mack Robinson’s greatest athletic achievement almost never happened.

Jesse Owens’ shoes may have been the only thing that stopped Mack Robinson’s greatest athletic achievement from being even greater.

But Robinson showed Hitler that greatness has nothing to do with the color of a person’s skin, and then showed America that athletic talent has nothing to do with a person’s ability to be great.

The 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin were, in Hitler’s eyes, a chance to show the world that the blonde-haired, blue-eyed Aryan race was supreme to all others. The official Nazi publication, the Völkischer Beobachter, wrote that Jews and Black people should not even be allowed to compete. In response, a number of countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, and France lobbied for the Games to be relocated or boycotted entirely. In the USA, the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) stated that participating in Hitler’s Olympics could be seen as supporting the Third Reich; the Philadelphia Tribune, the county’s oldest African American newspaper, countered that Black victories would help undermine Hitler’s belief in Aryan supremacy.

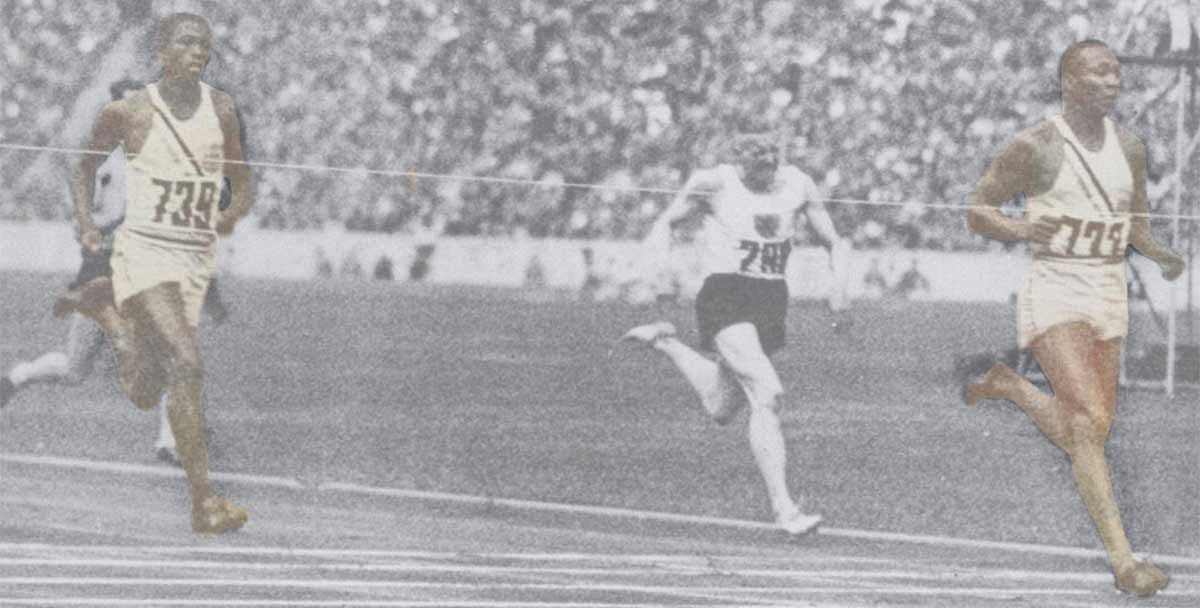

The Games eventually went ahead—and were the first-ever to be televised, and the first with a torch relay—and on August 5, 1936, the 21-year-old Robinson made his way to the starting line of the Olympiastadion track for the 200-meter final. The 100,000-seat stadium was adorned with swastikas, and Hitler himself was in the crowd, looking on.

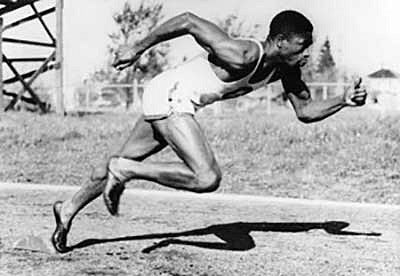

Robinson, wearing the same spikes he’d used to compete for Pasadena Junior College that spring, dug his toes into the divots in the cinder track, looked into the turn ahead of him, and at the sound of the starter’s pistol leapt forward, every sinew in his body straining to pick up every ounce of speed his chiseled frame could muster, legs churning, knees lifted high, arms pumping, elbows back as his wrists brushed past his hips with each blur of a step, around the curve and down the home straight with the roar of 100,000 Germans reverberating inside his head and Dutch sprinter and future SS volunteer Tinus Osendarp on his heels, until he crossed the finish line.

Twenty-one-point-one seconds—approximately the amount of time it took to read the previous paragraph—was all Robinson needed to run 200 meters, equaling the Olympic record he had set in the semifinals. But one step ahead of him, with a new world record of 20.7 seconds and wearing a new prototype of Adidas shoe made by company founder Adi Dassler himself, was J.C. “Jesse” Owens, the Ohio State star who had just claimed the third of the four gold medals he would win in Berlin.

“[Mack] had the mindset that he was going to beat any and everybody,” said Wayne Robinson, Mack’s son. “The shoes that he ran in were the same shoes he ran in when he was in college. He didn't get a pair of brand-new track shoes, but Jesse Owens did. And so, because of that, he came that close to beating Jesse Owens.”

Led by Owens, a fan favorite who was mobbed by autograph seekers throughout his time in Berlin, the USA’s African American athletes dominated the athletics events and won 14 medals. An enraged Hitler declared, “The Americans should have been ashamed of themselves for allowing their medals to be won by Negroes,” and called for Black athletes to be banned from further competitions. Robinson simply packed up his Team USA gear and his silver medal, left the Olympic village, and made the 10-day voyage back to the United States—a country where he could not legally drink out of the same water fountains or swim in the same pools as his White teammates.

In 1936, Rosa Parks was a 23-year-old newlywed, and the Montgomery Bus Boycott was still 19 years away. Martin Luther King Jr. was a seven-year-old schoolboy in Atlanta, 27 years away from leading the March on Washington. Emmitt Till’s parents were still teenagers, three years away from even meeting each other. The very idea of a Civil Rights Act was unthinkable.

None of the 18 African American athletes on Robinson’s Olympic team were invited to the White House; President Franklin Roosevelt hosted only the White athletes. Owens recounted later on how a ticker tape parade was thrown in his honor in New York, as well as a reception at the Waldorf Astoria. When the four-time gold medalist arrived at the Waldorf, he was made to take the freight elevator to his own reception.

Meanwhile, Robinson attended Pasadena Junior College for one more year and then transferred to the University of Oregon to study physical education and compete for the Webfoots. In 1938, he won the NCAA and AAU titles in the 220-yard dash for the UO, and was the Pacific Coast Champion in the long jump.

“He would always talk about how beautiful Oregon was,” said Wayne. ”I remember as a kid he always talked about how beautiful it was. I believe he really loved being there. I know there’s a difference from California to Oregon, I get it, but there was something about that place.

“He tried to get my uncle Jack to go there. That’s what I understand. You know when you love a school, you want everybody to go with you. So what I remember is that he loved the school so much that he tried to get my uncle Jack to go there, but UCLA snatched him up right before Oregon could get him.”

Mack had set PJC’s long jump record before leaving for the UO. His younger brother, on the verge of following Mack to Eugene, bested him by an inch, which got the attention of UCLA. Were it not for that solitary inch in the long jump, Jack Robinson—better known to the world as Jackie Robinson, the man who broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball, earned six All-Star honors, and won the 1955 World Series with the Brooklyn Dodgers—would’ve been an Oregon alumnus as well.

For Mack, an Olympic silver medalist and the brother of a baseball legend, competition ran through his veins. His children recall memories of riding in the car with him going 100 miles per hour on the freeway, just to get ahead of another car.

“You talk about a competitor? My dad didn’t like anybody in front of him,” recalled Wayne. “There’s only really one freeway to get you from Pasadena to LA, and that’s one of the oldest freeways. It’s right off Arroyo Seco, and it takes you from Pasadena. It has a lot of curves. And the freeway, my dad had to be doing close to 100 miles an hour. I know that because when I got of age, I said, ‘You can’t drive me no more.’ He scared my wife so much. When he saw anybody in front of him, he would speed up just enough to be first. He always wanted to be first, and he lived his life like that. It’s a miracle that I’m alive today. It’s a miracle that any one of us are alive today. Because that’s how he drove, and that’s how he lived.”

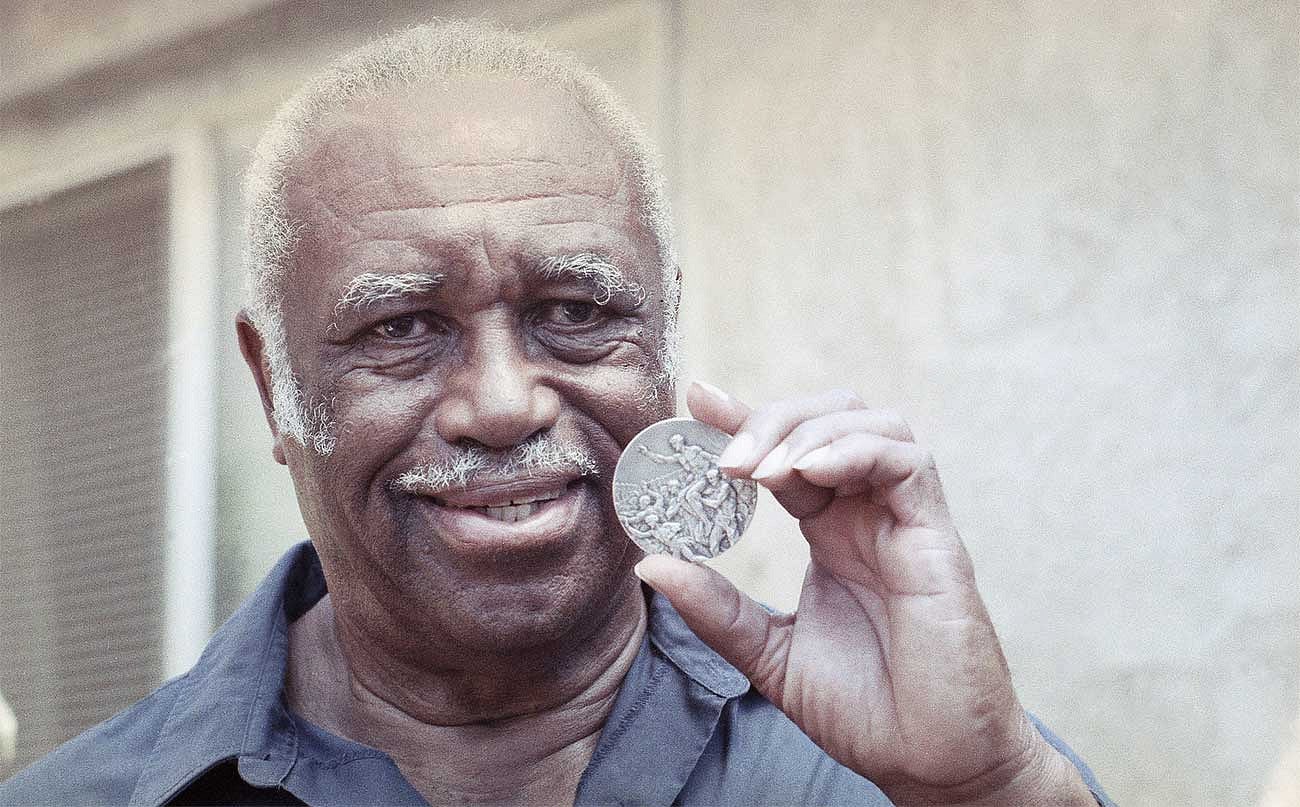

“[He used to say] ‘My silver medal has as much gold as Jesse’s gold medal,” said Edward Robinson, another of Mack’s sons. “His thing was, ‘I have as much gold in my silver medal as Jesse has in his gold medal.’ He’s not taking second place to anybody. ‘I got a silver medal only because I was just behind Jesse. But understand, I look at my silver medal as a gold medal. Can’t tell me anything different.’ And that’s such a high standard, and it shows the athlete in him.”

Robinson’s children remember the influence being in Olympic family had on them. “We came up an Olympic family,” daughter Kathy Robinson Young shared. “When daddy got invitations to go places to speak with the Olympics, to go to Helms Bakery over there in Culver City, we had to go. There was no ifs, ands, or buts about it. We had to dress and be there on time. We all had to go, and they made room for daddy’s kids. I remember sometimes we had to walk two by two down the street going someplace because there’s so many of us going to an event that daddy made sure that we were part of.”

Robinson stayed involved with the US Olympic Committee, and in 1984 was chosen to be one of the athletes who would carry the Olympic flag into the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum during the opening ceremony for the Olympic Games. His love of the Olympic spirit also fueled him as a fan. A vocal supporter of the Special Olympics, Robinson volunteered his time and would applaud the athletes during meets and take photos of them—again, with his children in tow.

“He was always cheering them on, saying ‘Rah rah rah,’” recalled Kathy.

But Mack Robinson didn’t just touch the lives of his family members and Special Olympics athletes—his impact was felt throughout all of Pasadena, and eventually, across the country.

Mack and his brothers did not have an idyllic childhood in Pasadena. Jackie, for one, refused to return to the city due to the way Edgar, the eldest brother, was treated. “I’m trying to say this in the best words as possible, but racism was very prevalent,” said Wayne.

Mack left the UO in 1941 without finishing his degree and returned to Pasadena to take care of his family. He swept the streets in his Olympic uniform—“He had enough pride within himself to say, ‘At least I can sweep the streets and put food on my table for my family,’” said Edward. However, Robinson lost his job as a street sweeper when Pasadena fired all of its Black employees out of spite after a judge ordered the city to desegregate its public pools.

Undeterred, Robinson continued working to improve the community. As an advocate for youth he worked to create opportunities to keep them out of trouble through the creation of playgrounds, YMCAs, and swimming pools, lobbied for better books in the libraries, and was well-known among local lawmakers.

“By him being a child of, and now resident of Pasadena, my father knew one thing you could do was go down to City Hall, and the word I think he would say was, ‘You could raise a stink,’ said Wayne. “He would go down to City Hall whenever there was a planning meeting. My father was so involved with them, they hated to see him come to the to the board meetings.

“I’ll never forget when I was in the fifth or sixth grade, we were split up when busing came in. And so they asked us in the sixth grade if we wanted to go down to the Board of Education. I thought my dad was going to tell me, ‘No, you can’t go down there and talk to all these Board of Education people.’ Oh no, it was everything but that. ‘Go on down there and voice what you have to say.’ When I got the green light, the green light was on. I told them who I was: ‘I’m Wayne Robinson and I don’t agree with the busing issue and I want to go to my community junior high right here where I can walk to school.’ They said, ‘Who are you? Oh, you’re Wayne Robinson? Oh Lord, this is Mack’s son.’ They were probably sitting in their seats going, ‘Oh my God, here we go. We’ve got to deal with another Mack.’”

“He fought like no one else could fight,” said Edward, who remembers passing out fliers with his father to increase involvement in town hall meetings.

Robinson worked tirelessly for the Pasadena community. He demanded that parks were clean, safe, and free of drugs and alcohol. He insisted that pools be made available during the summer months. He volunteered at Lemon Grove Park. In 1992, when riots broke out across Los Angeles after four members of the Los Angeles Police Department were acquitted by a jury after being filmed beating Rodney King, Mack Robinson was one of the community leaders called upon to help restore peace.

“If you don’t have much guidance, it leaves too much room,” said Edward of Mack’s motivation for working with Pasadena’s youth. “If you don’t have a mentor, you don’t have someone out there saying, ‘No, don’t do that, do this. Why don’t you go here, and don’t go there. Let’s stay at home and don’t go out.’ If you don’t have that structure available to you, then you’re sort of just learning on the fly. You’re learning as a group, you’re learning together what you think is fun, but may not be the right kind of fun.”

“He grew up through everything,” echoed Wayne. “He’s seen wars, he’s seen presidents changing, he’s gone through the Civil Rights Movement. And in all of that he could see in Pasadena, and across the nation, if you just don’t have structure and opportunity for children to exercise their minds and their natural ability, they’re going to go in a different direction that won’t be as productive. He stood in City Hall, he stood up in these board meetings, and stood up for education, and stood up for those less fortunate.”

Mack didn’t limit his generosity to just Pasadena, either. After taking Wayne, then 12, to visit an aunt in Georgia and seeing the dilapidated house in which she lived—“It was a shotgun house with a blanket over the door,” Wayne said—Mack rallied the Pasadena community to donate items to help.

“We filled up an entire Bekins Van Lines truck with clothes,” said Wayne. “He had worked out something—I don’t know how he did it, by being persistent; a lot of things come about by you being persistent—he was able to get Bekins Van Lines along with American Airlines to fly all the clothing down to Georgia and Mississippi and have it distributed to community centers, churches, and schools so those who are less fortunate would have something to put on.”

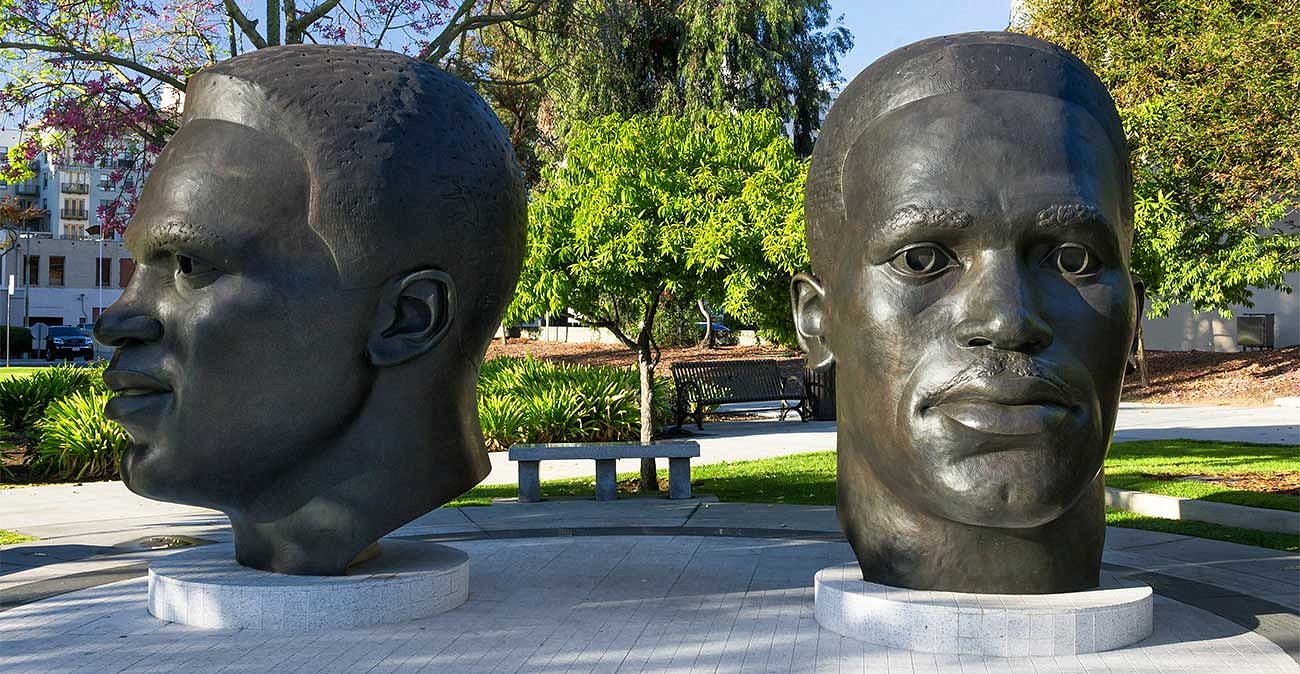

In 1981, Robinson was inducted into the Oregon Sports Hall of Fame in recognition of his exploits in Eugene. In 1995, he was also inducted into the UO Hall of Fame. Two years later, the Pasadena Robinson Memorial was dedicated in his hometown; the nine-foot-tall bust of Mack faces City Hall in acknowledgement of the work he did for the community.

Mack Robinson, who was born to a family of sharecroppers on July 18, 1914, in Cairo, Georgia, and went on to become an Olympic hero who went to Nazi Germany and helped show Adolf Hitler up in front of the world before becoming a community organizer who improved the lives of countless others, died of complications from diabetes on March 12, 2000. Later that year, Pasadena City College—PJC had been renamed in 1954—dedicated its stadium to him while the United States Postal Service named its new Pasadena post office the “Matthew ‘Mack’ Robinson Post Office Building.”

Mack’s legacy lives on through his children, who are active in their own community and their own church and work to make a difference wherever they can. Not everyone can be a star athlete, they say, but everyone can make the world around them a little better for others.

“It’s something we do as a family and a community and a church that’s bigger than us,” said Wayne. “You want your legacy to be something. What you do on the field is one thing. But just like they award the football players the Walter Payton Man of the Year Award, this and that, it’s what you do outside of your notoriety and platform you’re on [that counts]. I often say that God is going to reward us for what we do. We can have a whole lot of talk, but when we share food, when we share putting something on somebody’s back, that’s where we’ll reap rewards. And I believe, even in the latter years of my dad’s life, that he reaped something for the good that he did.”