It’s 6 a.m. on a summer morning on the Oregon coast, and a dozen undergraduate students wearing tall rubber boots are piling into vans. They’re juggling granola bars and notebooks, texting friends who are running late.

It’s not the first time this crew has been up at the crack of dawn this summer. They’re taking an invertebrate zoology course at the Oregon Institute of Marine Biology. And today’s field trip — to nearby Cape Arago State Park to go tidepooling — is just one on a full roster.

“Every day, we go out at least once. Our teachers can bring us down to the docks, and we get to see the things we're learning about,” said Ryan McCarthy, a senior marine biology major.

The OIMB campus, nestled in the fishing village of Charleston, is centered around experiential, hands-on learning. Marine biology majors at the University of Oregon must spend three terms in residence at the Charleston campus, taking upper-level classes.

Here, students’ study subjects are their neighbors. It’s a short walk from the dorms down to the docks, where a net dipped into the water pulls up plankton and tiny invertebrates. In labs, plastic five-gallon buckets from the hardware store house critters like sea stars and hagfish that were collected just offshore. By design, the learning opportunities spill far beyond the wood-shingled cottages where students attend more traditional classes.

Marine biology majors at the University of Oregon spend three terms in residence at the Oregon Institute of Marine Biology, our coastal campus in Charleston, Oregon.

Here they take upper-level classes and gain practical, hands-on experience with laboratory and field research techniques.

Offering researchers access to an unusual range of habitat diversity, the OIMB campus is home to the laboratories of several UO faculty members.

OIMB also hosts the University of Oregon's Charleston Marine Life Center. Part aquarium and part museum, this is an educational resource for the public to connect with diverse environments, histories, and animals of the Oregon Coast.

At Cape Arago, students head down a short-but-steep trail to the beach. With an especially low tide this morning, exposed rocks stretch across the protected cove.

The boots are a necessity: The rocks are draped with slippery seaweed and kelp. To uncover the creatures hiding in tidepools, one must climb into them, lifting up small rocks and clumps of seaweed. One misstep, and water could soak your socks.

For the next two hours, the students are scattered across the rocky intertidal zone. Patrick Baker, a visiting professor from the University of Florida who is teaching this summer’s invertebrate zoology class, is their guide. Sea lions bark from distant rocks and Baker repeats a warning to never approach a sea lion, no matter how cute their pups might be.

One of the missions today is to hunt for brittle stars — sea star relatives with skinny, wiry arms that tangle into spaghetti-like blobs — to bring back to the lab. It’s also a chance for students to practice identifying some of the many species they’ve learned about in the classroom.

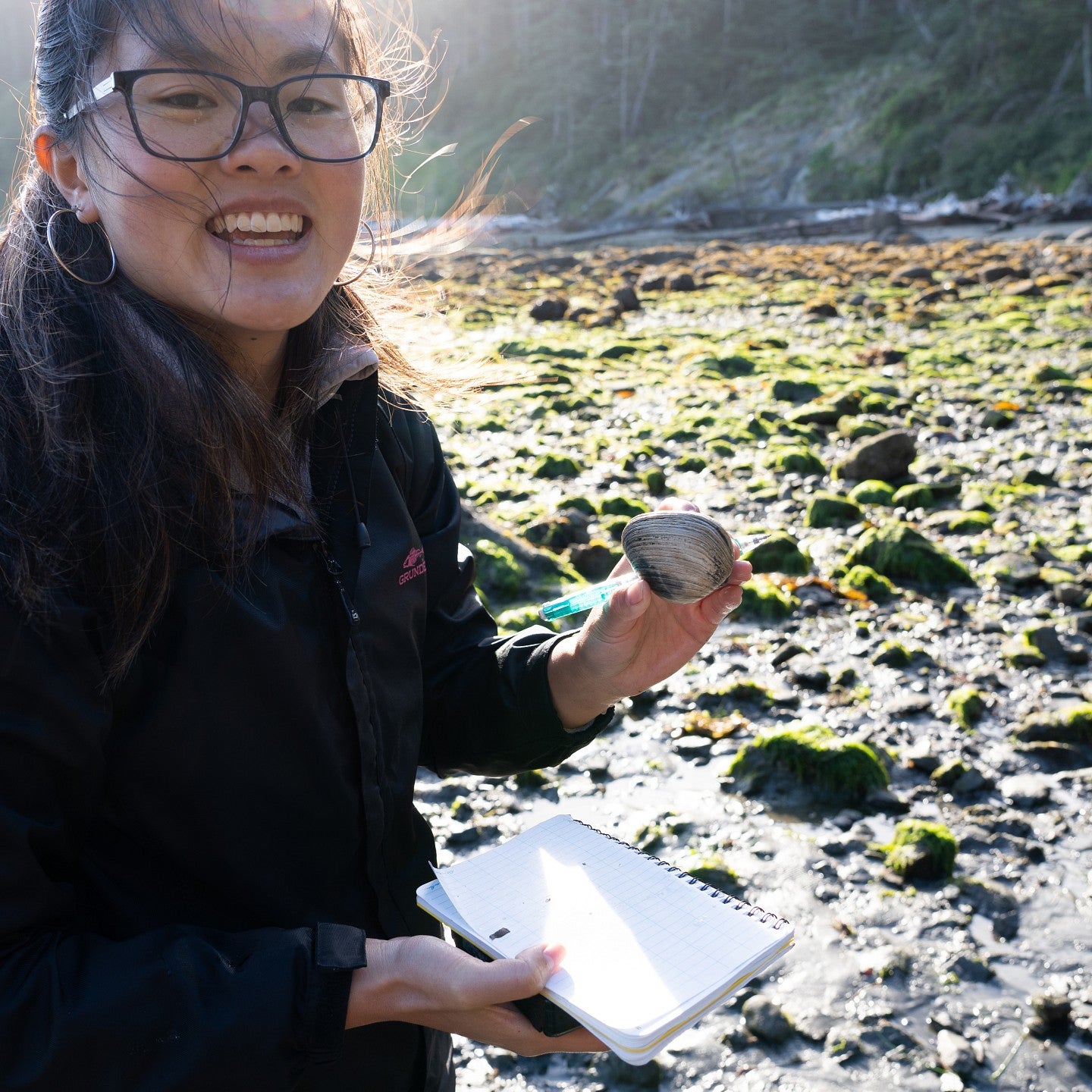

Senior Vithika Goyal examines a tidepool find.

Logen Williams, a senior, sifts through kelp in search of organisms.

Instructor Patrick Baker discusses tidepool ecology with students Kate Hurley, Cassandra Nelson, and Lauren Mcnamara.

Vithika Goyal makes another fascinating discovery.

Every so often, Baker will scoop up something notable, and nearby students will cluster around to hear more about it. There are shrieks as something big slithers by underwater, and excited squeals when someone spots an ethereal white nudibranch — Dirona albolineata,otherwise known by its common name: sea slug. Smartphones and cameras emerge from pockets and plastic bags that protect them from an accidental plunge into the chilly water.

“It’s especially fun to see how in this class setting we’re all sharing our findings, and we want to share the cool things we see,” said Sofia Fox, a senior majoring in marine biology and dance.

“I think I’ve gained a different perspective on what working in the field can be. . . . Just having that more connected experience between what I'm seeing and what I’m learning has opened up a new way of learning and understanding.”

Since 1924 — when summer classes used tents for dormitories and laboratories — the University of Oregon has been teaching and conducting research in marine biology on the Southern Oregon coast.

Now located at a permanent, 100-acre campus near the ocean entrance to Coos Bay, the Oregon Institute of Marine Biology (OIMB) offers convenient access to some of the most spectacular places on earth to study marine organisms and ecosystems.

The class is immersive, in every sense of the word: The students focus deeply on investigating the tidepools. There are no distractions here — cell phone reception is spotty at best and there’s a summer camp-like atmosphere to the whole endeavor. It’s a world removed from everyday cares. As the sun rises, the sound of the surf, which had receded at the low tide, becomes an ever-encroaching sound that reminds the students they’d better start picking their way back to dry land before the morning’s classroom is once again submerged.

“I think I’ve gained a different perspective on what working in the field can be. This is the first time that I've been able to consistently be working on marine biology all the time,” said Fox. Back in Eugene, they’re juggling classes in all different disciplines, plus a full roster of extracurriculars. “I think also just having that more connected experience between what I'm seeing and what I’m learning has opened up a new way of learning and understanding.”

“Being on the coast is one of my favorite experiences of my college career — it’s truly incredible,” said McCarthy.

“Pretty much anyone, as long as they meet the prerequisites, can spend a term here,” Fox said. “It’s valuable experience no matter what field people are pursuing, just to get that hands-on experience.”

Laurel Hamers is a science writer with University Communications. Kelley Christensen is director of research communications with the Office of the Vice President of Research and Innovation.

OIMB is located on traditional lands of the Miluk, Hanis and Athabaskan people, many of the whom are now citizens of the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians, and of the Coquille Indian Tribe.