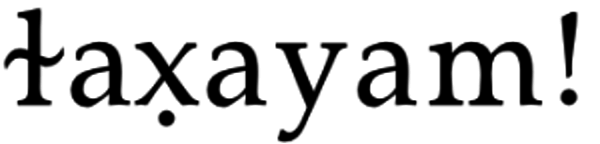

Hear this humble greeting in Chinuk Wawa, the Native trade language of western Oregon and the Pacific Northwest:

What it Means to Be on This Land

By Norma Trefen

Multicultural Academic Counselor and Native/Indigenous Retention Specialist

First, let me start with a territorial land acknowledgment

The University of Oregon is located on Kalapuya Ilihi, the traditional indigenous homeland of the Kalapuya people. Following treaties between 1851 and 1855, Kalapuya people were dispossessed of their indigenous homeland by the United States government and forcibly removed to the Coast Reservation in Western Oregon. Today, descendants are citizens of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon and the Confederated Tribes of the Siletz Indians of Oregon, and continue to make important contributions in their communities, at UO, and across the land we now refer to as Oregon and throughout the globe.

It’s important to begin any conversation with a land acknowledgment. This centers the conversation to our land, community, and tribes. I ask each and every one of you about what it means to be on this land.

Native American Heritage Month was conceived of more than 100 years ago. In 1915, the annual gathering of the Congress of the American Indian Association directed its president to ask the United States to observe American Indian Day. Seventy-five years later, the US government enacted a resolution designating November as National American Indian Heritage Month.

Native American Heritage Month is a time of reflection, and sometimes that reflection can be hard. But it’s also time of celebration and building community.

Ch’ee-la, my name is Norma Trefren and I am an enrolled citizen of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians. I am a multicultural academic counselor and Native/Indigenous retention specialist. I work for the Center for Multicultural Academic Excellence. My role as an academic counselor is to focus on retention of Native students. I have been in this role since summer of 2019.

I know this year looks radically different than years past, but it’s still important to share space and build community, as you hear in the words of the students in this story. As Kirby Brown, director of Native American Studies eloquently states in his interview, “It’s a challenge to build community when you’re not in community.”

Join us to find community in events like the weekly hybrid Native Study Hall and NASU that will be hosting virtual meetings and virtual Indigenous Womxn’s Wellness.

Celebrating Native American Heritage Month during a global pandemic and nationwide protests against injustices while in college leads me to call on the presence of my Indigenous ancestors. I am White Mountain Apache and Choctaw from the Fort Apache Indian Reservation in Arizona. I am a sophomore, PPPM major, and the current reigning Miss Indian University of Oregon. As a student at UO, I am grateful for the community I have built and access to safe spaces, although I miss my peers tremendously.

The past months of this pandemic meant not being able to see my reservation or attend the Native American Student Union’s Thursday potlucks on campus. For me, this has been lonesome and difficult seeing the impact COVID-19 has had. However, I am reminded of a quote I once heard, “Take care of yourself because one day you will be the storyteller.”

In my Native culture, we rely heavily on oral teachings for speaking and teaching Apache language, singing Apache songs, and passing the stories to the next generation. These stories honor our ancestors and teach the importance of identity. I think of the day we all will become ancestors and the stories they will tell about us. How will they introduce us when they speak our names?

I celebrate Native American Heritage Month for generations from now. My hope is a story is told of how despite the chaos and injustice of this country our people were resilient and took up space within higher education. I celebrate being able to access my degree for my advisers, for good health, and for the friendships I have made at UO.

I celebrate for the Native students who are the first in their family to attend college, the ones who are almost done with their degree or middle school, the ones in a trade, and the ones who did not take a traditional college path. I celebrate for the ones before me, the ones after me, and the ones here with me now. Most importantly, I celebrate the stories and ancestors in me.

Jorney Baldwin

Major: Family Human Services; Journalism

Minor: Native American studies

Enrolled member in the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Tribe

Joining the ARC and participating in NASU events last year changed my life. I have been able to learn about not only other’s traditions, cultures, and dreams, but I also was able to engage in a community that helped me learn more about myself in many different aspects. Through all of this, I was able to relate to people I never thought I would have and made some of the best connections with students and faculty, and they turned into my family.

Lofanitani Aisea

Major: Asian/Indigenous Race and Ethnic Studies

Modoc Klamath Black Tongan

I really appreciate the Native American and Indigenous Studies staff. Since I got to UO they have been there for me and helped me navigate paces on campus as I transitioned into college life as a freshman and throughout my undergrad years. Even before I got to college I would go to summer camps and academies and they would be there offering the resources and help I didn’t know I needed yet. A lot of the reasons why I am able to achieve and go forward in both my life and my academics are because of the love and support I have received from my Indigenous communities.

A conversation with Native American students about the UO

Ryan Reed: Codirector of the Native American Student Union, environmental studies major, affiliated—the Karuk, Hupa, and Yurok peoples of Northern California.

Patrick Phillips: Provost and Senior Vice President.

Angela Noah: Reigning Miss Indian University of Oregon; member of the White Mountain Apache Tribe, with a connection to the Oklahoma Choctaw tribes.

Temerity Bauer: Codirector of the Native American Student Union, member of Round Valley Indian Tribes.

Sapsik'ʷałá Teacher Education Program

The Sapsik'ʷałá program is based on the belief that “Education Strengthens our People.” Sapsik'ʷałá, is an Ichishkíin/Sahaptin word which translates to “teacher” in English. The name represents the program’s cultural values for self-determination of education for Tribal people.

The program began in 2002 to address the dire need for American Indian/Alaska Native teachers. The program collaborates with all nine federally recognized sovereign Indian nations of Oregon and the UOTeach master’s program to deliver a pathway for Indigenous people to become teachers within their communities.

“Beautiful, Resistant, and Resilient”

A conversation with Kirby Brown, Associate Professor of English

By Jason Stone, University Communications

An enrolled citizen of the Cherokee Nation, Kirby Brown is the author of Stoking the Fire: Nationhood in Cherokee Writing, 1907–1970, a recipient of the 2019–2021 Norman H. Brown Faculty Fellowship in the Liberal Arts, and director of the UO Native American Studies program.

How would you describe your sense of Indigenous identity?

To be an Indigenous person is to be from a place, from a People, and from a history and culture that is tied to family and the extensive relations that define our contemporary communities and tribal nations. There’s an incredible diversity to contemporary Native identity that is complicated and even messy in some respects, but always beautiful, resistant, and resilient.

One of your research interests is “Native American Modernisms”—what do you mean by this term?

To the extent that “modern” represents “the new” or “innovation” or “adaptation,” Indigenous People have always been “modern.” Prior to contact, we created and exchanged technologies and knowledge with one another and built relations across communities. So in one sense, thinking about Native American Modernism or Indigenous modernities complicates our perception of “the modern” and its relationship to “Indianness” on a conceptual level.

In literary studies, modernism is understood in a more particular way to mean an intentional break from the past and the embrace of the new via radical formal innovation in aesthetic production. It’s conventionally been situated around the 1910s–1940s, and in the United States discussions around modernism have tended to focus on a small cohort of mostly white writers from metropolitan centers.

In recent years, however, the field has begun to look at multiple modernisms taking place outside of European and American national and imperial centers. That’s really expanded our perspectives of what, when, and where “modernity” is, and the multiple ways it gets translated into aesthetic forms. We’re now examining the works of Native and Indigenous writers and writers from other historically marginalized communities as active producers and critics of modernity who have been previously excluded from those discussions.

Can you speak to some of the specific challenges that the COVID era has created for Native communities on our campus?

It’s a real challenge to build community when you’re not in community. Our cultural spaces are essential to this effort, and our colleagues in places like the Many Nations Longhouse , the Native American Student Union, the Native American and Indigenous Studies ARC, and the Sapsik'ʷałá Program are going to some extraordinary efforts in very difficult circumstances to continue their service to community.

What does inclusion mean to you—and how do we achieve more of it at the UO?

First, we acknowledge that we’re on Kalapuya ilihi, the traditional homeland of the Kalapuya people, whose descendants are citizens of two federally recognized sovereign tribal nations: The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde and the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians. We acknowledge that the very existence of the University of Oregon is predicated fundamentally on their forced removal, and that there is a direct correlation between those acts of violence and dispossession and the current underrepresentation of Native American students, faculty, and staff on this campus.

What inclusion means to me is that you recognize and own that history, accept the contemporary responsibilities and obligations it demands, and do whatever it takes to structurally address those issues.

Native American Resources

Campus Resources

UO Libraries Resources for Indigenous American Research

Native American Studies Courses - Fall 2020

ENG 244 - Intro Native Amer Literature with Kirby Brown

ANTH 443 - North American Archaeology with Moss M

ICH 101 - 1st Yr Ichishkíin

All Native American Studies Courses

A message from VP for Equity and Inclusion, Yvette Alex-Assensoh