By DAMIAN FOLEY

Watering holes in the African savanna can be lifesavers. As the temperature creeps above 90 degrees, animals gather to quench their thirsts while escaping the sweltering summer heat. While the sun bears down, elephants bathe and spray themselves and each other with pressurized bursts of water from their trunks. Giraffes splay their legs and crane their necks to drink the refreshing liquid below. Hippos submerge themselves, cooling down while taking pressure off their bulky frames.

But sometimes, the lifesaver can be a killer.

A gulp of poisoned water is followed by lethargy, then paralyzing seizures, sudden cardiac arrest, and death.

And then? The final step is the ultimate indignity.

The savanna’s apex predator isn’t the lion, hippopotamus, or crocodile—it’s a poacher armed with cyanide that kills and a saw that dismembers, removing horns and tusks so that they can be sold on the black market.

And the poacher’s biggest threat might just be an architecture student at the University of Oregon.

As a child growing up in Eugene, Jess Kokkeler had a treehouse in his yard, and considered it his sanctuary.

Now an interior architecture student in the College of Design, Kokkeler, a member of the class of 2018, is letting his inner child run wild.

Supported in part by the Pacific Northwest Preservation Field School Director’s Scholarship Fund and the Ion Lewis Traveling Scholarship in Architecture, Kokkeler is studying forest service lookout towers across Oregon. He assesses their aesthetic qualities and functionality, as well as the materials of which they’re made.

“Places I like to go out in the woods have towers, and I’d hike to those and think, ‘What a cool place.’ There’s a hideout with epic views and very basic architecture that’s also sustainable,” Kokkeler says. “Career-wise, I want to go to these cool, remote spots and build things that

are beautiful.”

In September 2016, Kokkeler went to Zimbabwe to study the extreme sport tourism market near Victoria Falls, one of the world’s largest, most voluminous waterfalls. Before leaving Oregon, he contacted the International Anti-Poaching Federation (IAPF) and arranged to join a group that was fighting poaching at Zimbabwe’s 6,000-acre Stanley and Livingstone lodge and private game reserve.

The reserve is the only place in the area to see the “big five”—black rhinos, Cape buffalo, lions, leopards, and elephants—and it is a recognized Intensive Protection Zone for the critically endangered black rhino.

Elephants, rhinos, and other behemoths play a very real role in tourism, with people flocking from all around the world to go on safaris and see them in the wild. A 2012 study conducted by North-West University in South Africa determined that a single elephant in the wild could be worth as much as $3.5 million in tourism over the course of its lifetime.

And yet, despite what they are worth to the environment and the economy, elephants and other big game are routinely slaughtered.

The global illegal wildlife trade generates between $7 billion and $23 billion each year, with demand for everything from ivory jewelry made of elephant tusks to traditional medicines derived from rhino horns funding terrorist organizations and conflicts in developing countries. In 2012, members of a militia from Chad rode into neighboring Cameroon on horseback and killed 600 elephants using AK-47s and rocket-propelled grenades. The following year, 300 elephants in Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park were killed in one day when poachers poured cyanide into watering holes; animals drinking from the contaminated watering holes died and predators feeding on the poisoned carcasses met the same fate.

During the 1980s, an estimated 100,000 elephants were killed across Africa; Chad now has just 2 percent of the 50,000 elephants that roamed the country 50 years ago. A study conducted by the University of Massachusetts Amherst estimated 8 percent of the African elephant population is lost every year, primarily due to poaching.

Reserves such as the Stanley and Livingstone are fenced, but that does not mean the animals in the expansive park are safe. Poachers create holes in the fences and make their way through the bush in search of their prey. Combating them is a constant struggle—but one in which Kokkeler has been able to help.

“Once we arrived we went out into the bush and they acclimated us to their operations and how to safely conduct ourselves, and pretty much right away we started doing patrols of the area to familiarize ourselves with the area, doing game counts and looking for signs of poachers,” Kokkeler says. “Throughout the process they educated us on what the rangers did and how they operated, so we could be better ambassadors for their efforts.”

Kokkeler first helped remedy a problem with ranger patrols, which are conducted in old, often-rickety land cruisers. The rangers drive fast, knowing speed is the key to catching poachers, but that also means the doors fly open while bouncing over uneven terrain; Kokkeler devised a way to keep the doors closed—even at high speeds—using magnets.

While on patrols, Kokkeler evaluated the rangers’ needs, and devised an altogether different use for the lookout towers he had been studying in Oregon: combating poachers.

“We use fire lookout towers for land conservation and early detection of fires. I thought (officials) could use towers for antipoaching purposes as well,” he says. “It takes very few people to see a large area.”

When it comes to finding poachers, height is key. If you have to locate a single person in a large area filled with acacia trees, standing on the hood of a dusty land cruiser won’t cut it. Drones are out of the question, as the park is close to Victoria Falls Airport.

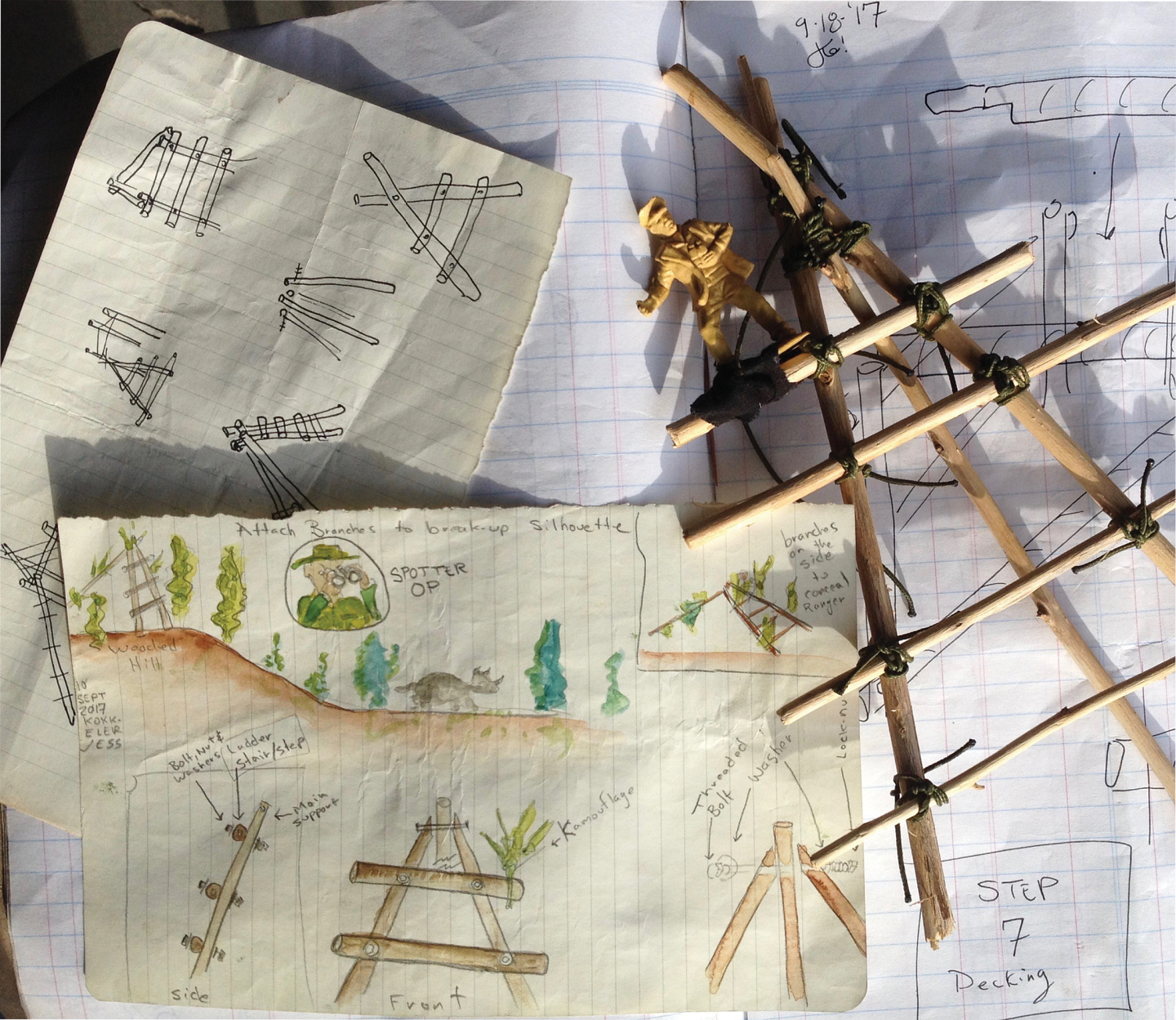

As Kokkeler explored the park and familiarized himself with the terrain, he jotted down ideas in his logbook:

- Maximize ranger efficiency with limited manpower, tools and with found or repurposed materials.

- Utilize remedial design that can easily be replicated in the field by rangers with limited construction knowledge.

- Save lives-minimize risk of rangers and endangered species.

- Aid animal conservation through design.

He sketched out a collapsible tower that could be raised and lowered quickly and kept out of sight of poachers. The rangers had a region of the park in mind: it was so remote that gunshots from poachers couldn’t be heard, an easy spot for them to reach once they’d entered the park, and in a dead spot for radio; the tower could act as a communications relay point. The structure had to be of enough size and stability to accommodate multiple rangers overnight in all weather conditions, and it had to be safe from the reach of the wildlife. It also had to be easy to construct with the limited resources on hand.

First, the team took an inventory of tools at their disposal. An old chainsaw was discarded for safety reasons, but a drill with dull bits proved useful. The wood came from old rhino “bomas,” temporary enclosures that hold animals before they’re relocated. They didn’t have rope, but Kokkeler had a hammock, and the straps from that were used to help raise and lower logs that had been cut and shaped with hatchets.

“A regular part of design is quickly adapting to changes,” Kokkeler says. “Knowing I had limited materials but the support of these people, I was confident that we could move forward with the tower.”

Kokkeler also needed to purchase the supplies they didn’t have. Concerned that he would be unable to withdraw sufficient funds from ATMs in the economically struggling country, he again improvised.

“I hiked over to Zambia; it’s only a few miles,” Kokkeler says. “I went to the ATM and took out cash. Then I went to the exchange booth to get American dollars because the Zambian money, kwacha, they don’t take in Zimbabwe, but the exchange place didn’t have any American dollars or money acceptable in Zimbabwe. I had to take the kwacha to a bazaar in Victoria Falls, and there was a guy in a grey market where he’s not legally allowed to exchange the money, but he did at a 10 percent rate.”

The final step was the construction. Kokkeler drew up a plan, and four days and $67 later the rangers had a new 20-foot-tall lookout tower: a rudimentary ladder leading to a wooden platform and hammock with sweeping views of the valley, and safe from predators roaming the reserve.

“It was a primitive design,” Kokkeler says. “It was based roughly on the designs I studied through the scholarships to study fire lookout towers. There is a classic argument in design whether form should follow function or the opposite; in this case, function preceded form. The restrictions of the area and funding limited the style and aesthetic of the project.”

Aided by Kokkeler’s tower, the fight against poaching continues at the Stanley and Livingstone reserve, and indeed all across Africa.

Picket Chabwedzeka, senior warden and anti-poaching manager at Stanley and Livingstone, says, “We are using numerous anti-poaching techniques to counter poaching activities, but the tower is actively assisting us with our operation. This is war against individuals and syndicated groups who are poaching wildlife in Zimbabwe.”

The first night, Kokkeler and three others stayed in the tower. As the sun set, they could hear elephants grazing nearby. As it rose again the following morning, giraffes walked past.

“It was fun to be able to apply design to animal conservation, but it’s not solving the problem,” Kokkeler says. “The IAPF and the guys on the ground are making the most difference, and this is just a small way of helping them out.”

Damian Foley is assistant director of marketing and communications for the UO Alumni Association.