Where will you be on December 21?

Dan Wojcik knows where he'll be: in Yucatán, Mexico, at the ancient Mayan site of Chichén Itzá—the hub of the hubbub over a prophecy that many believe specifies that day as the last in a 5,125-year Mayan time cycle that began in 3114 b.c. Like Wojcik, thousands are traveling to ancient Mayan sites in southern Mexico and Guatemala—or gathering at locales closer to home—to mark the occasion, which some see as ushering in a new level of consciousness but others fear will be marked by more apocalyptic disruptions—fire, flood, or clashes in the cosmos.

"I need to be there to document this moment in a respectful way," says Wojcik, director of the folklore program and associate professor in the English department at the University of Oregon, and one of few folklorists in the country who specialize in apocalyptic themes. "It's a fascinating happening in the history of religion, and certainly in the history of millennialism. It's sort of uncharted territory—almost a counterculture apocalypse of the world, something we've never seen before."

What intrigues Wojcik about the Mayan 2012 prophecy—and distinguishes it from the many end-times predictions that have preceded it—is that it has been cultivated and spread largely via the Internet, and hence has developed an especially broad, eclectic, and leaderless following.

"In terms of the diversity of prophecy beliefs, the 2012 phenomenon has everything," he says. "Indigo children, UFOs, Mother Earth returning, DNA transforming, galactic alignment, the emergence of the noosphere, the arrival of Quetzalcoatl, and hundreds of other ideas. This eclectic mixture of beliefs, a millennial stew of apocalyptic expectation, often confuses eschatologists [those who study end-times beliefs], and many of them don't take 2012 beliefs seriously. But this represents a new dynamic in the creation of belief in the twenty-first century in the age of the Internet—a mix-up or mash-up, a smorgasbord or cafeteria of beliefs. But it's not necessarily frivolous. It deserves academic attention and analysis, like other new religious movements."

According to historians of Mayan culture, the Mayan Long Count calendar completes its current "Great Cycle" on a day that corresponds to December 21, 2012. The Great Cycle began on August 11, 3114 b.c., and comprised 13 b'ak'tuns, each of which was made up of 144,000 days. The cycle has lasted for approximately 5,125 years. The Mayans apparently said little about what would occur at the end of this current cycle, but various individuals have offered their spin on what the move into the fourteenth b'ak'tun portends.

As the 12/21/12 date crept closer, a plethora of blogs and websites appeared on the Internet, some accompanied by advertisements for survivalist paraphernalia, such as seed bags and generators. The 2009 release of the movie 2012, which focused on the death-and-destruction end of the apocalyptic spectrum, prompted a wave of news stories related to the prophecy. The 2008 Complete Idiot's Guide to 2012 attempted to explain the prophecy's significance in the context of Mayan culture and discussed the meaning of rare celestial events the authors believe will occur close to or on December 21, including the sun's supposed alignment with the center of the Milky Way. "The 2012 alignment will interrupt the flow of energy reaching the Earth from the galaxy," wrote Guide authors Synthia Andrews and Colin Andrews. "The birth of the solstice New Year will also be the birth of a whole new age filled with new energy."

Apocalypse believers are far from a fringe group. A 2012 Reuters poll found that nearly 15 percent of people worldwide—and 22 percent in the United States—believe the world will end during their lifetimes and 10 percent think the Mayan calendar could signify it will happen in 2012.

Scientific institutions that usually remain above the apocalyptic fray have waded in to address the fears of a jumpy public. NASA even has a 2012-focused web page devoted to quelling anxiety about wayward planets, breakaway continents, or a polar shift in the near future. (The site, at nasa.gov/topics/earth/features/2012.html, states bluntly and authoritatively: "December 21, 2012, won't be the end of the world.") Venues around the country, including the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI), are showing a video presentation debunking rumors about pending astronomical calamities. Jim Todd, director of space science education at OMSI, says the program is being offered twice a day through the end of the year. "It seems only appropriate that we end it at that time," he quips.

* * *

End of world scenarios have been a staple of Western thought for centuries, tracing back to ancient Jewish, Greek, and Roman beliefs and appearing in the Book of Genesis (Noah and the ark) and the Book of Revelation. Religious apocalypse themes, says Wojcik, author of the 1997 book The End of the World as We Know It: Faith, Fatalism, and Apocalypse in America, involve some kind of cataclysm wrought by gods displeased by human hubris or misdeeds; most offer believers the promise of a better life in postapocalyptic times, a golden age free of suffering, evil, and injustice.

From its beginnings, Wojcik writes, the New World seemed to nurture apocalyptic—or millennialist—beliefs. Christopher Columbus believed his explorations were helping to prepare for the millennial kingdom on Earth, and the early Puritans settled their communities with an eye toward Christ's Second Coming.

A series of believers warned of coming doom throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, among them the Millerites, followers of biblical scholar William Miller, who were greatly disappointed when the world didn't end in 1843 or 1844 as he had prophesied.

Some ardent millennialists lived their ethos communally—for example, the Shakers and members of the Oneida Community in upstate New York. Millennial beliefs were a cornerstone of emerging religious denominations in the New World, such as Seventh-Day Adventists, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (or Mormons), and Jehovah's Witnesses. The Native American Ghost Dance movement of the late 1800s, Wojcik writes, prophesied divine destruction of white settlers who had decimated Native cultures, promising a return to presettlement times.

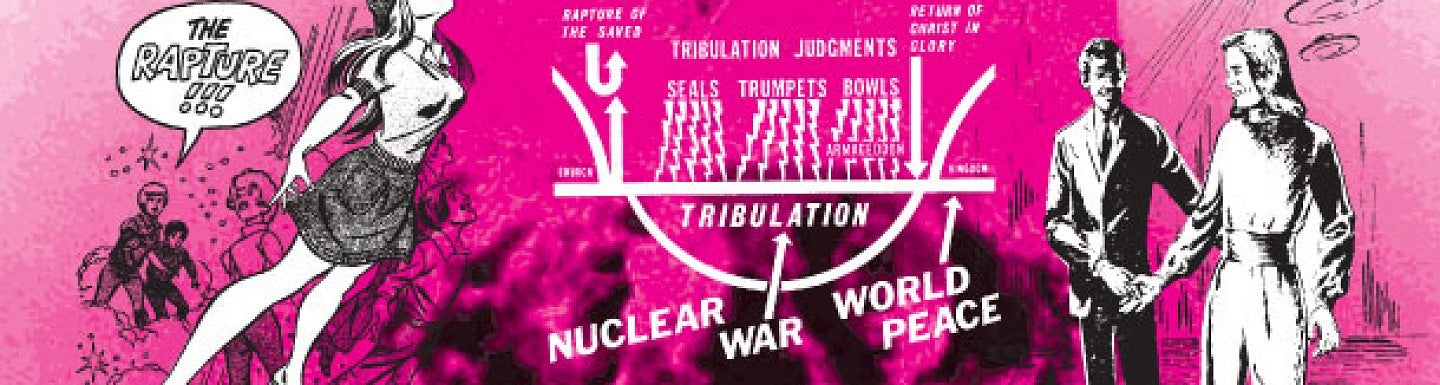

The twentieth century saw several extreme manifestations of apocalyptic beliefs, the consummate example being the 1978 murder-suicide of 914 followers of Jim Jones and his People's Temple in Guyana. In the United States today, many Christians embrace the concept of the Rapture, a belief that people of faith will be taken up to heaven and protected from the ravages of an earthly apocalypse.

The turn to the twenty-first century created a flurry of Y2K-related end-times furor, mostly around fears of a technological doom as computers struggled with the shift to the year 2000. A more recent apocalyptic prophecy made news last year, when Harold Camping, the president of Family Radio, a Christian broadcasting network based in Oakland, California, spent millions spreading the word that the end of the world would occur on May 21, 2011. When the day came and went without incident, Camping revised the date to October 21. "We have learned the very painful lesson that all of creation is in God's hands and He will end time in His time, not ours," Camping wrote in a statement after that prophecy, too, failed to materialize.

Wojcik notes that the modern era also ushered in a new type of secular apocalyptic belief, in which the destruction of the world comes from human actions and doesn't include the component of spiritual redemption. Fears of nuclear annihilation spurred the wave of secular apocalyptic fears, but as that threat ebbed, others arose to take its place: pandemics, famine, overpopulation, terrorism, and global climate change. Young people, in particular, have bought into what many see as an inevitable destruction of the world—a 1995 Gallup poll found three teens in ten "fearing the world may come to an end in their lifetime."

* * *

With fears that the end is near occupying our national consciousness with some regularity, why has the Mayan prophecy, more than others, garnered so much interest? In addition to the ease of communication afforded by the Internet, Wojcik and others think it is because this prophecy includes the element of salvation. "There's the sense that everything is going to be upgraded; a widely held belief that there will be a spiritual transformation of humanity," he says.

"We all want our fears to be alleviated," he says. "The fascinating, ancient Mayan culture holds out the possibility to think there is hope. Even if it is hope for access to wisdom, for a return to a proper understanding. The thinking is, 'The Mayans had it figured out. Maybe I can access that wisdom and be ready.'"

Eden Sky, a southern Oregon resident who studied with Argüelles and has used a modern application of Mayan time to publish her "13-Moon Natural Time Calendar" for the past 18 years, calls the coming time "a huge and mysterious moment." She says the change heralded by the prophecy is the end of a world age, not the end of the world.

"The main component of the new world age is a shift into the recognition of the interconnectedness of life, and constructing our culture from that understanding," she says. Change is not going to fall from the sky, she stresses, but will come from individuals' actions. "My focus is to encourage

people to align with the recognition that we are shifting world ages, and from that inspiration and commitment, to participate in the process."

* * *

As some focus on the salvation end of the apocalypse spectrum, others have their eyes on more material prizes. For the past year, the Mexican states that encompass traditional Mayan lands—Campeche, Chiapas, Quintana Roo, Tabasco, and Yucatán—as well the countries of Belize and Guatemala, have been gearing up for a tsunami of tourists as the portentous date approaches. In July 2011, Mexican president Felipe Calderón announced the launch of Mundo Maya 2012, a program to promote tourism and understanding of Mayan culture and to prepare for what he estimated would be upwards of 50 million tourists in the coming year.

Former Eugene resident Rosa Maria Mondragon Flores now lives in the Mayan town of Tulum, in the state of Quintana Roo on the Yucatán Peninsula. She says many people are expected to come for "12/21," and among them will be several members of her family from the United States who will participate in rituals at the nearby ruins. "I don't look at it as an ending, but a new beginning," she says. "A new awareness coming to take place. It is a very exciting time, and I feel privileged to be there."

Closer to home, "preppers"—those determined to be prepared for the worst—continue to boost sales of camping gear, guns, and ammo. Retail sales for the national outfitter Cabela's, which has a store in Springfield, increased 16.9 percent in the year's second quarter, according to Matthew Carr with the Investment U website. The company is so in tune with the apocalyptic trend, Carr writes, "It even offers a doomsday prepper-focused catalogue." This past September, Costco offered a year's supply of canned foods—grains, meat, protein, dairy, fruits, and vegetables—for $1,200.

The rising apocalyptic tide isn't floating all boats equally. At Powell's Books in Portland, end-times sales have fallen off since the beginning of the year, says Gerry Donaghy, new book purchasing supervisor. "As a subject matter, the interest has waned," he says. But farther south, sales are up at the Soul Connection Bookstore in Shasta City, California, possibly because of its proximity to Mount Shasta, one of the sites of the 1987 Harmonic Convergence and considered by many to be a vortex of spiritual energy. "We've seen a 30 percent increase from last year," says owner Bruce Catlin. "People are pursuing spiritual tools. It's a waking-up time for a lot of people—2012 is a springboard into the future."

But even if it doesn't lead to profits, people are using the possibility of an imminent end-time as a hook for a variety of agendas. Singles in Sedona, Arizona, a New Age hot spot, can sign up for a round of doomsday dating. Doomsday daters might consider participating in the Birthing the Fifth World Gathering, being held in Sedona from December 19 to 21. For those seeking security, Mother Nature Network offers a list of the "Ten Best Places to Survive the Apocalypse," including a 112,544-square-foot underground bunker beneath the Greenbrier Resort in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, commissioned in 1958 to house Congress in case of a nuclear event. A three-bedroom, 2,300-square-foot "Silohome" in the Adirondacks, refashioned from an unused Atlas-F missile silo, is another possibility.

Armchair doomers looking for vicarious survivalist experiences have an array of options, as handy as the television remote. This fall, NBC began airing its dystopic Revolution on Monday nights, featuring a Diana-ish, arrow-shooting heroine, sword fights, and bad-guy militiamen roaming a forlorn landscape near Chicago 15 years after a mysterious, countrywide power outage. Doomsday Preppers is in its second season on NatGeo, AMC is continuing its popular apocalyptic-zombie drama The Walking Dead, and TNT is offering a second season of Falling Skies, in which a former Boston University history professor leads a band of soldiers to confront alien invaders. Unfortunately, Spike TV cancelled its proposed competition series Last Family on Earth, which was to have awarded the family with the best survival smarts a bunker in which to spend December 21.

"We're having the party on December 20," she says. "Just in case the world does end."

While Wojcik has become a devotee of these apocalyptic-themed brews, he'll likely have to find something more readily available in the Yucatán to toast with on his birthday this year—as it just happens to fall on the momentous date Mayans inscribed for posterity thousands of years ago. Whatever occurs, Wojcik is prepared for it to be memorable. "I'm thinking the vibe and celebration at ancient Mayan sites will be kind of like the Country Fair, or Burning Man," he says. "Spiritual, but fun."

—By Alice Tallmadge

Alice Tallmadge is a freelance writer and adjunct instructor in the UO School of Journalism and Communication.