One evening last year, Jared Acosta-King was in a laboratory in Huestis Hall, diluting a potently odorous chemical called isopentylamine.

The psychology major and community college transfer had earned a spot in the lab of Matt Smear, an assistant psychology professor, through his classroom inquisitiveness. But Acosta-King had limited experience working with odors; he was curious about isopentylamine and took a sniff too close to the bottle—and he experienced an indescribably bad smell.

“It was like a gnarly alcohol. It felt like I was inhaling a fireball,” says Acosta-King, 29. “The fear response was immense.”

He became so disoriented and panic-stricken that fellow students took him to an emergency room.

As Acosta-King regained his composure, he was seized by another spasm of fear—that Smear would kick him out of the lab. The assistant professor quickly allayed those concerns, which were rooted in the insecurity ingrained in Acosta-King from an upbringing fractured by poverty and trauma.

“My default setting,” he says, “is I’m dumb and I don’t belong.”

Many college students have wrestled with fear of rejection or failure. For Acosta-King, it ran deeper.

Prior to enrolling at the UO, he struggled to believe he could move past his early challenges. The voice in his head told him he wasn’t good enough, but one thing sustained him: an innate obsession with knowledge and discovery. That drive to understand the world was a beacon during dark times, and it has led Acosta-King to status as one of the UO’s promising young scholars.

In 2006, Acosta-King, 17 years old and estranged from his family, dropped out of school and was evicted from his apartment in Billings, Montana. He spent years homeless, he says, living in a van, couch-surfing, and drinking to numb frigid temperatures and shame.

Acosta-King started to stabilize after moving into his sister’s apartment in Coos Bay in 2013. He hit the books with intensity at Southwestern Oregon Community College, driven by the fear that this would be his last chance to make something of himself. He got sober, started getting A’s, and in 2016 transferred to the UO for its standout psychology department.

Acosta-King had little working knowledge of higher education. But even before he had started his undergraduate studies, he was the type of guy who’d hear a joke about quantum physics and spend hours reading and researching until he understood it.

In Smear’s biopsychology class, he was energized by the professor’s research on the brains of mice and how they process scents to find a mate or identify a predator. Smear’s encouragement proved as meaningful as his knowledge.

“He doesn’t talk down to people. He took the time you needed to really help you understand a concept,” Acosta-King says. “I thought if I was in research, I wanted to be like that guy.”

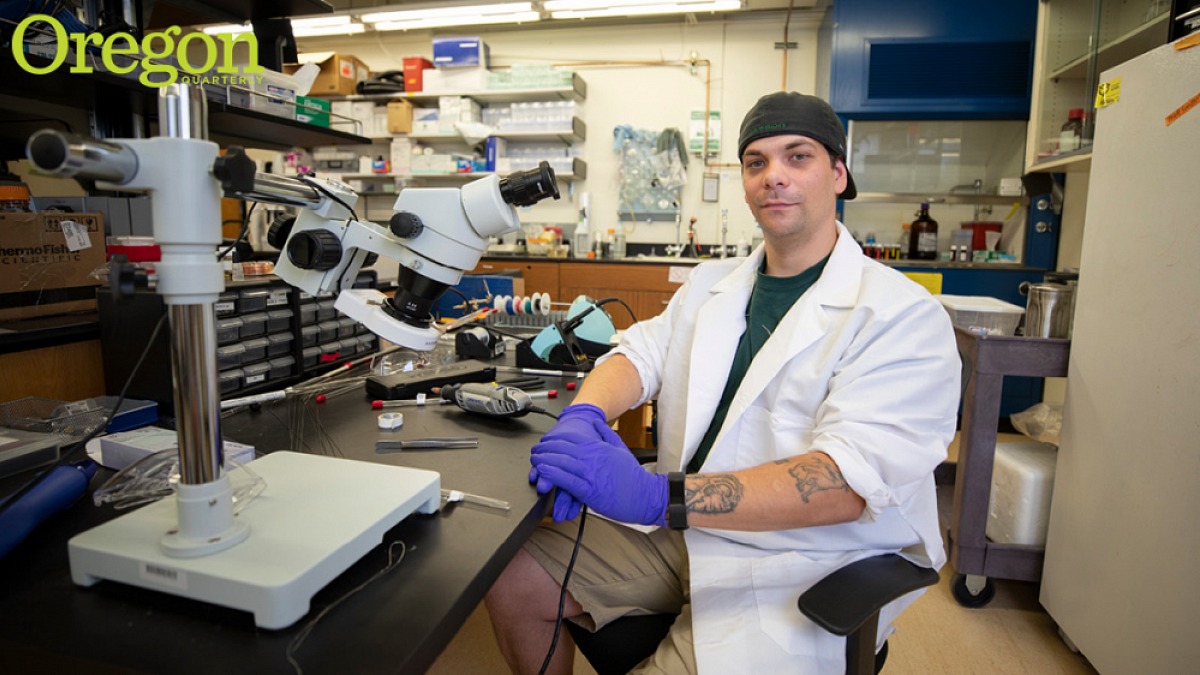

With Smear and other role models for guidance, Acosta-King experienced an academic awakening through research. He distinguished himself in the lab, working with the professor’s team on projects that explored the olfactory neurons in mice. He branched out, pursuing questions about the autistic brain and why it discerns scents differently.

“The truth is I never had the environment where I was encouraged, and once I had that, I proved I was smart,” Acosta-King says. “Students like me, if we’re given the right kind of care and supportive, constructive criticism, we can do really amazing things. I’m a testament to that.”

That drive propelled Acosta-King to graduation in May as a McNair Scholar, an award that supports promising, underprivileged UO students for doctoral programs. Acosta-King spent the summer working in Smear’s lab, where he’ll begin earning his PhD in psychology this fall.

Acosta-King will continue to study the olfactory mechanisms of mice, which are vital to the critters finding food and identifying predators. The neurological nodes of the nose are similar structurally across all mammals, but poorly understood compared to other senses. Thus, the inner workings of a mouse brain can reveal discoveries about our own.

During his time at the UO, Acosta-King has methodically replaced self-doubt with self-belief, and that’s made him an assiduous evaluator of research. He analyzes projects published in scientific journals and critiques the validity of the author’s interpretations.

“The growth in his confidence has been the most important thing in his development so far,” Smear says. “He deals with that imposter syndrome more than the rest of us because of his background, and he’s still learning how smart he is.”

—By Marc Dadigan

Marc Dadigan, a freelance writer and photographer in Redding, California, covers Native American issues, the environment, mental health, and higher education.