“I love this. I just love this,” Sarah Livia Brightwood Szekely ’83 says. She says this out loud, but she’s really talking more to herself than to the patient workers who watch as she pickaxes the ground with short, powerful strokes. It’s a warm, sunny, blazingly blue-sky afternoon in Baja California, and Sarah is busy excavating a meandering canal for a water feature she designed. Dressed in baggy shorts and a fading Healing Plants and Herbs T-shirt, her long, straight, shot-with-gray hair hanging loose, no jewelry, no make-up, she looks like a dirt-under-the-nails gardener (which she is), a hands-on landscaper (which she is), and a ’70s-era alternative culture Eugenean (which she was). What she doesn’t look like is president of a sprawling, upscale, internationally renowned fitness and health resort that was recently voted World’s Best Destination Spa by the readers of Travel + Leisure.

The woman wielding the pickax with a sheen of sweat across her brow runs the show at Rancho La Puerta—3,000 acres, 400 employees, 150 guests, eleven gyms, three health centers, a six-acre organic farm, and a world-class culinary school. The place is part shake-your-booty fitness resort, part spiritual retreat, with classes ranging from treadmill trekking to Tibetan singing bowls, from deep-water aerobics to dream decoding. The ranch, an early model of sustainability, was founded seventy years ago by Sarah’s parents. Her father was a distinguished Hungarian professor, a linguist, philosopher, psychologist, and natural-living experimenter. A man ahead of his time, he published Cosmos Man and Society and Medicine Tomorrow in 1928, precursors to the whole foods–raw food movement. Newspapers of the day dubbed him a “health cultist” for promoting organic farming, vegetarianism, juice fasts, and holistic medicine. The author of more than eighty books, a student of Buddhism, and a follower of the Essenes, a mystic sect reputed to have authored the Dead Sea Scrolls, he was equal parts intellectual and oddball. Her mother, a Brooklyn-born follower of the professor’s esoteric philosophies, became an astute businesswoman who guided the creation of the ranch, became a spa industry leader, and went on to launch the famously luxurious Golden Door fitness resort in California.

Intent on her task, Sarah picks up one football-sized rock after another, hefting them easily, examining each in turn, noting the quality and color of the granite, from pink to silver to dark gray. She turns to the workers who are prepping a special cement mixture and speaks to them in soft, swift, perfectly accented Spanish. She learned Spanish before she learned English, courtesy of the Mexican-born nanny who cared for her while her mother was busy building the business. Finally, she chooses a rock and places it along the side of the shallow canal, positioning it in a concavity she stops to dig. She steps back, looks, then carefully turns the rock ten degrees so that its shape aligns perfectly with the curve of the canal. She gets down on her knees and trowels dirt around the rock until it is one-third buried.

The trick in creating this landscape feature—in creating all the landscapes Sarah designs throughout the thirty-two lush acres of ranch gardens—is to manipulate the environment while making it seem unmanipulated. The trick is to create, out of earth, stone, and plants, a cultural, horticultural, and personal statement—a living expression—and make it feel as if it has always been there. Only it’s not a trick. It’s a core belief, a guiding philosophy Sarah learned from University of Oregon landscape architecture professor Ron Lovinger, the man she calls both mentor and muse, who easily returns her compliment. He says that the years he spent first teaching and then working with Sarah are among his most cherished memories.

Sarah was his student in the mid-’70s. She had come to the University of Oregon for its well-known landscape architecture program but also because she was hungry for seasons. It was fall when she first visited, one of those golden late October days that makes it impossible not to fall in love with the Willamette Valley. She remembers apples and pumpkins. She remembers the energy and the high spirit of the place. She remembers professors who were friendly, welcoming, and informal. When she took her first course with Ron Lovinger, Understanding Landscapes, he didn’t know who she was. He didn’t know about the ranch and the extraordinary opportunities it would present this nineteen year old. But he knew immediately that she was someone special, a girl with a sophisticated awareness of the world and a strong but gentle sense of self. He taught her that landscape is ideas embedded with meaning. He taught her that landscape is great poetic expression, a living art form. He taught her the language of landscape, and she has been speaking it, fluently, ever since.

* * *

Later that afternoon, following a quick shower and a change of T-shirts, Sarah is walking the grounds of Parque del Profesor, a twenty-eight-acre city park in Tecate, the border town forty miles south of San Diego that is home to the ranch. The park is located on land the ranch donated to Fundación La Puerta, the nonprofit arm of Rancho La Puerta, of which Sarah is president. The foundation maintains the park for the citizens of Tecate. It is a breathtaking public space with a vast stone plaza that descends by wide, three-sided stone staircases onto a soccer field. With 3,900-foot Mount Kuchumaa, a sacred site, in the background, and the wide vista of tiered stone work, it looks like Machu Picchu and manages to feel both holy and wholly accessible.

She’s proud of this project for many reasons. It honors her father, the profesor of Parque del Profesor, whom she reveres and, even thirty-some-odd years after his death, quotes often—and unselfconsciously. (One of her favorites—not surprisingly—is “the most noble of all professions is gardening.”) The park was a deliberative, collaborative project, which is how she likes to work. It embedded the ranch, through Fundación La Puerta, in the cultural life of the place she considers home. And it gave her a chance to work with Ron Lovinger, who designed it.

Sarah was his student in 1979, the year her father died. By then, he knew who she was. She approached him with the idea of the park, and he immediately immersed himself in the writings of her father. Then, one night, in a dream, the man himself, Professor Edmond Szekely, visited the UO professor, who suddenly wonders aloud whether he should be telling this story. What might it sound like for an internationally renowned and respected landscape architect to admit to having a vision? But he tells it anyway. Edmond appeared and explained what he wanted, and when Ron Lovinger awoke, he knew just what the park would look like. He starts to describe the plan, using almost the same words Sarah has used, but then he stops himself.

“It’s much easier if I draw it,” he says. He grabs a notebook and looks briefly and skeptically at the pen sitting beside it, a ballpoint freebie from a bank. He takes a moment to extract a fountain pen from his jacket pocket, uncaps it, and begins to draw. It’s been more than thirty years since he designed the park, but he sketches the topography quickly and effortlessly. He talks, like Sarah, about the points of the compass and the four elements of earth, air, fire, and water, how they live in the culture, in the landscape, and in the park. Designing the park was not about imposing his will on a space, he says, but about bringing already embedded ideas to life. When he showed the plan to Deborah, Sarah’s mother, she cried.

* * *

For Sarah, creating the park—which took fifteen years—opened the door to a different but complementary life. She would design gardens for the ranch while still an undergraduate at the UO. She would become project director and create and oversee the development of major expansions and renovations. But she would also live the life of an activist, both in Eugene and in Tecate, loyal to both places, dividing her time but somehow multiplying not dividing her energy.

In Eugene, she continued to study landscape architecture along with ecology and Spanish. She formed networks. She put down roots, literally and otherwise. In the early ’80s, she joined the newly formed Aprovecho Research Center, a Willamette Valley nonprofit organization dedicated to appropriate technology and sustainable living skills. After graduation, in between creating her own extensive gardens on land near Spencer Butte, she taught permaculture design at Aprovecho, helped implement a soil conservation training program in Nicaragua, and worked as a volunteer with the Council for Human Rights in Latin America.

At Parque del Profesor, Sarah strolls along a curved path that leads from the stone plaza up a hillock to Las Piedras Environmental Education Center. Serious environmental education takes place here in this fanciful complex of classrooms designed to look like boulders and caves. All sixty of Tecate’s schools have sent students to Las Piedras to learn about water and watersheds, soil and seeds, geology and the chaparral ecosystem. The kids, sitting in round, soft spaces that feel like animal burrows, learn to become the next generation of ecocitizens.

Sarah walks into the anteroom of one of the structures. The packed earth floor absorbs her footfalls; a shaft of afternoon sun finds its way through a small curve of stained glass inset high in the rock wall. The air inside is cool and dry. She stops to listen to the silence, then flings her arms out to her sides and starts to sing—no words, just a snippet of a tune that the walls absorb and soften. She laughs. “The sound in here is so. . . . ” She doesn’t finish the thought and doesn’t have to. The sound is as enchanted as the place itself. Sarah walks through a narrow, winding passage between the first room and a small amphitheater. The seats in here are two carved stone benches in the shape of snakes. Sarah has a story about that. She has a story about everything: the eight masons who worked ten years to craft this place, the amazing Enrique Ceballos, the ecologist and sculptor who created it, the stunning wrought iron door handles, the carved wooden doors, the little mats the kids sit on. Everything is on purpose. Everything is function. Everything is art.

* * *

At six the next morning, the air at the ranch smells like rosemary and eucalyptus, then roses layered on roses, then a blast of honeysuckle tempered by sage. Sarah takes big, deep breaths of it and, as she hikes through an oak grove on her way to the ranch’s organic farm, she tells stories of her childhood: the horses, chickens, and goats, the cottage garden, the pristine river, the long walks through the foothills of Mount Kuchumaa, the tiny village of Tecate. This was the landscape that nourished her and one she is now helping preserve through the conservation easement.

Sarah stops to take note of a plant that grows only when the season happens to be wet enough, which leads to a discussion of climate change, which leads to a discussion of water use, which becomes a primer on wastewater management at the ranch. With Sarah, every moment is a teaching moment, but not in a know-it-all way or in a way that robs the moment of its real-time experience. It’s more like everything interests her, and she wants to share that interest. Life is learning. The two cannot be separated.

She passes a flowering tree, reaches out to pluck a small, plump, white petal and pops it in her mouth. “Pineapple guava flower,” she says, letting the petal melt in her mouth. “Better even than the fruit.” She leans down to cradle another flower, marveling at its gorgeously complex structure. “Magical,” she says. Magical is a word she uses often when talking about plants. But in the same breath, she’ll say the plant’s Latin name and tick off the specifics of its habitat, growth cycle, soil preferences, and water requirements. The science doesn’t take away from the magic, and vice versa. Where she is heading this morning, Tres Estrellas, there is both magic and science.

Tres Estrellas is a meticulously tended six-acre organic farm that provides between 50 and 90 percent of the produce, depending on season, for the ranch and its guests. It was Sarah’s first big solo project back in the ’80s, both a choice, she says, and a calling. It continues to be her passion.

“Some people spend their money on fancy jewelry,” she says, smiling as she surveys the farm. “I spend it on vegetables.” Tended by eight full-time gardeners, the farm grows every row crop imaginable, including some that aren’t, like five different kinds of cilantro. There are apple, pear, apricot, fig, persimmon, plum, pomegranate, guava, and mulberry trees. There are ducks. There are one hundred chickens, some of which nest in big clay pots.

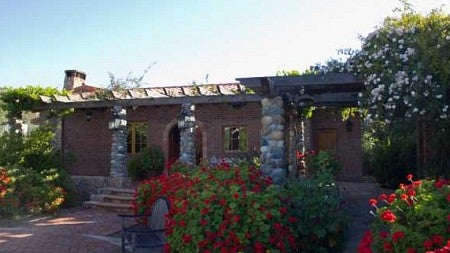

Eggs from these chickens are part of the breakfast waiting for her and a group of ranch guests at La Cocina Que Canta (the singing kitchen), the centerpiece of the farm. Sarah designed this cooking school and culinary center to host visiting chefs and cookbook authors, to teach organic Mexican-Mediterranean cuisine, and to showcase the cultural and artistic richness of the community. She walks across the patio and courtyard of La Cocina and through the covered portico, the transition from natural to built environment so subtle that it’s almost a surprise to find oneself inside. There’s the multistation master teaching kitchen and a very large, light-filled dining area. The space is somehow both expansive and intimate. There are hand-painted tiles and murals, carved fireplaces, woven tapestries, folk art, mirrors, wrought iron sculptures, every object, every detail a conscious choice. With Sarah and the cooking school and the farm and all the landscapes she’s imagined and designed on the ranch during the past thirty-five years, it’s about panorama and microcosm, the big picture and the small choice. It’s about big ideas and small stones placed individually along a hand-dug canal, about poetry and plants.

Breakfast is ready. The eggs, scrambled with red, yellow, and green peppers from the garden, are . . . Sarah almost says “magical,” but she catches herself and laughs. “Ummm,” she says instead, savoring the bite. Then she jumps up to pick mulberries from an overhanging tree and sprinkles them on her plate.

—By Lauren Kessler

Lauren Kessler’s most recent book is My Teenage Werewolf: A Mother, a Daughter, a Journey through the Thicket of Adolescence. She blogs about mother-daughter issues atwww.myteenagewerewolf.com. Kessler, MS ’75, directs the graduate program in literary nonfiction in the UO’s School of Journalism and Communication.