It was the image that pierced the public’s war-weary numbness: the lifeless form of a Syrian toddler on a Turkish beach—a grim end to his family’s desperate bid to flee the bloody civil war in their homeland. The death of three-year-old Aylan Kurdi in September 2015 was little more than a rounding error in a conflict that has now claimed 500,000-plus lives. But the heart-rending photograph put a human face on an otherwise-amorphous tragedy. Suddenly, people cared. The picture went viral. Donations to the Swedish Red Cross to aid Syrian refugees surged more than 50-fold.

The episode was a vivid demonstration of the power of compassion. But, according to Paul Slovic, also a display of its limits.

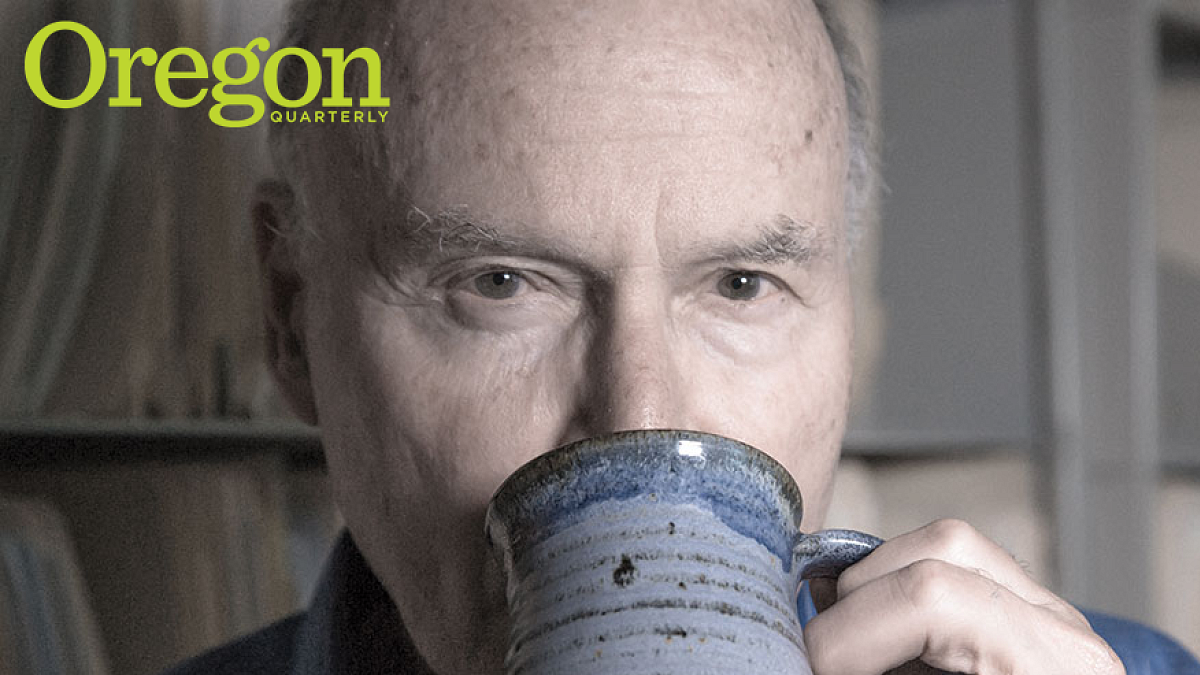

A UO professor of psychology and president and cofounder of the Eugene-based nonprofit institute Decision Research, Slovic has studied the vagaries of human compassion for two decades. As he tracked the outpouring of generosity following the photo’s publication, he also watched it fade. Less than two months after Aylan’s death lit up the Internet, giving to the aid agency was back to the level it’d been at beforehand. The slaughter in Syria continued unabated.

It’s a phenomenon Slovic has observed time and again: our supreme attunement to individual human suffering juxtaposed with a seeming inability to respond proportionately when multiple lives are on the line.

Over more than half a century, Slovic has helped foment a revolution in economics, transformed the way we evaluate the societal risks of hazardous activities and technologies, and established the central role emotion plays in decision-making.

Now, Slovic is asking, can we use psychology to ensure it doesn’t take an image like Aylan’s to wake us up to mass human suffering, and keep us caring?

“Compassion is a necessary but insufficient condition for action,” he says. “We’re trying to identify where we can rely on our intuitive feelings and where we need to think more analytically.”

UPENDING ECONOMICS

Slovic’s quest is the culmination of a long intellectual odyssey. As a graduate student at the University of Michigan and, later, at Eugene’s Oregon Research Institute (ORI) in the late 1950s and 1960s, Slovic and his colleagues pioneered a new branch of psychology concerned with how we make judgments and reach decisions. Their investigative tool of choice was the gamble—a way to distill subtle ideas about how we weigh risks and make choices into testable hypotheses that simulate real life.

“It’s a very clean way to study risk,” he says.

But there was nothing clean about its findings. Many were downright heretical.

With ORI colleague and Decision Research cofounder Sarah Lichtenstein, Slovic offered test subjects a low-odds wager to win a modest sum, or a long shot to hit the jackpot. People consistently said they “preferred” the safer bet but would pay more to play the outside chance with a bigger payout.

The behavior confounded a fundamental tenet of classical economics—if you prefer something, you should be willing to pay more for it.

“They demonstrated nonrational behavior in a way economists couldn’t walk away from,” says ex-ORI researcher and Decision Research cofounder Baruch Fischhoff, now Howard Heinz University Professor, Department of Engineering and Public Policy, at Carnegie Mellon University.

Slovic and Lichtenstein’s finding formed part of a groundswell of psychological evidence debunking the notion we behave strictly rationally in our financial dealings. Collectively, this work is credited with introducing psychology to economics.

RISK AND REWARD

In the early 1970s, geographer Gilbert White had a different gamble for Slovic to contemplate: “Why do people return after a flood or hurricane to risk it all again?”

Slovic didn’t have an answer, but it piqued his interest in people’s attitudes toward “society’s gambles” in the contexts of new technologies, natural hazards, and other risky activities. Evaluating the risks that these elements posed was then the preserve of a priesthood of technocrats who assessed them on strictly quantitative grounds, frequently dismissing public concern as superstitious or ill-informed. In work that was instrumental in giving the public a greater voice, Slovic, Lichtenstein, and Fischhoff showed that people’s objections to certain technologies reflected a risk calculus no less rational than the experts’. Prominent among the red flags: a sense of “dread” about a technology’s uncontrollability and catastrophic potential.

Slovic and his colleagues were converging on the notion of risk not just as something we calculate but as “a reflection of what we feel.”

They noticed something else too: people rated technologies and hazardous activities they liked as high in benefit and low in risk; those they didn’t like as high in risk and low in benefit.

This made no sense, says Ellen Peters, professor of psychology at Ohio State University, who took her PhD under Slovic at the UO and later collaborated with him. “In the real world, risk and benefit are positively correlated; high risks usually offer high benefit—a stock, for instance. If it were high risk and low benefit, it wouldn’t exist in the market; there’d be no demand.”

The team’s findings suggested emotions, such as dread, were coloring how people perceived risk.

“Risk and benefit went in opposite directions because people started with their feelings,” explains Slovic. “The feeling came first, then drove the risk-benefit judgment.” He and others christened this impulse “the affect heuristic,” a deeply-felt response to a situation that pervades our judgment and impels us to act.

Which brings us back to the raw image of Aylan: the emotionally charged feeling it evoked that moved thousands to contribute to aid efforts was pure affect, says Slovic.

THE LIMITS TO COMPASSION

It also mattered that the image focused on one individual. A 2014 study by Slovic, Daniel Västfjäll of Sweden’s Linköping University, the UO’s Marcus Mayorga and Peters found donations to a famine victim fell when a second, no-less deserving, victim was added to the fundraising appeal.

It’s not that we’re callous, Slovic says. Rather, our moral instinct—honed over an evolutionary heritage where tuning everything out to attend to immediate kin could mean the difference between life and death—is poorly adapted to modern life. Today, we need to respond to existential threats of a magnitude and abstraction unprecedented in human history, he points out.

Slovic compares the “psychic numbing” we feel in the face of mass atrocities to the sensation of illuminating a room with candles. The first candle presents a binary phenomenon—darkness, then light. But as more candles are lit, the additional brightness doesn’t register as dramatically. “The emotional system has few levels,” he says.

There’s more going on than limited emotional bandwidth though. Putting another crimp in our capacity to respond is a tendency to dwell on those we can’t help. This shouldn’t matter; it has no bearing on the value of the lives we can affect. Still, it encroaches. “It doesn’t feel as good to help someone when you realize there are others you can’t help,” says Slovic. “Our brain lets everything in. There’s no gatekeeper keeping irrelevant feelings from messing up relevant ones.”

And even when we feel we can make a difference, our charitable impulses can be thwarted.

In his early experiments, Slovic found that people deciding between equivalent options typically chose the most defensible one—a “bias that led them to violate their stated values,” he says. “Defensibility isn’t important when you’re considering what’s valuable to you—usually you don’t have to defend a value. But you do have to defend a choice.” Slovic and others later named this the “prominence effect.” For leaders confronting genocide, it may take the form of defaulting to national security considerations, even if this contravenes values about the sanctity of life. “You can’t go wrong protecting security,” says Slovic. “Risking it for nameless, faceless lives to which we’re numbed anyway is less defensible.”

Overall, the human mind is deeply flawed when it comes to responding to contemporary humanitarian challenges—it is visually fixated, easily overwhelmed, and prone to being hijacked by competing concerns. If this were where Slovic’s work ended, things would look bleak.

But he’s also putting this knowledge to work in an effort to motivate quicker, more humane responses to crises like genocide and global warming.

CRISIS MANAGEMENT

For starters, there’s value in simple awareness of our proclivities, says son Scott Slovic, professor of literature and environment at the University of Idaho. He and his father have joined forces to launch a website, “the arithmetic of compassion.” The goal is to alert people to the barriers we face to wrapping our minds around mass suffering and design mechanisms that can overcome these obstacles to action.

“Just putting a name to a psychological tendency by being able to say, ‘I feel my compassion fading’ or ‘I feel I can’t be effective,’ even though what I can contribute could make a difference, can help us control our minds,” says Scott Slovic.

Father and son have also cowritten a book, Numbers and Nerves—featuring contributions from activists and authors—about appreciating the importance of the human stories behind numbers in an age of big data.

Slovic has also designed action steps people can take to bolster their instincts with more deliberative faculties. Compassion supplies the impetus for action, says Slovic, but by itself lacks the staying power to sustain meaningful long-term responses to humanitarian crises.

Accordingly, he’s teamed with legal scholars and other specialists to suggest practical ways to mobilize action by joining reason and compassion. These proposals include ways to frame discussions so national security concerns don’t automatically eclipse saving lives; frameworks for international intervention to stop bloodshed; and supplementing data points prepared for decision-makers with narratives on the human suffering behind them, plus images to further drive this home.

Offering creative tools for converting compassion into effective action is a fitting capstone to a career fueled by deeply held convictions about social justice that Slovic shares with his wife, Roz. Until her retirement in 2010, Roz was a faculty member in the College of Education at the UO; now, she’s active in helping settle refugees in Eugene. Slovic’s work relates no less to humanitarian crises closer to home, he points out. “We see statistical data on homelessness, poverty, and lack of access to adequate health care, but don’t think about the lives affected. We’re underreacting even in our own backyard.”

Lean and spry at 79 from a lifelong running habit, Slovic shows scant sign of slowing down. Working out of Decision Research’s off-campus offices near downtown Eugene, he maintains a work rate that’d be the envy of someone half his age. Over the past two years, he’s cowritten more than 30 academic articles, op-eds, and book chapters. Last year, he was inducted into the National Academy of Sciences, joining eight other UO faculty members.

“He applies himself to areas where new knowledge can have extraordinary impact, and he’s willing to dive into difficult, unpleasant topics,” says Robert O’Connor, codirector of the Decision, Risk, and Management Sciences Program at the National Science Foundation.

“To do what’s intellectually and socially important has always motivated him,” adds Scott Slovic. “He’s been fascinated by the work since my earliest memories. It’s been more than half a century of excitement.”

It’s a labor of love, but one that comes with a keen sense of urgency, says his father.

“It’s about how we can survive in a world that’s growing more and more dangerous.”

SHARP SHOOTER

Slovic started out as an ambivalent student. “My real interest was basketball, but you had to go to class to play,” he recounts. Still, the empirical spirit of a born scientist was apparent early on in his love of the game—“I enjoyed seeing how, with practice, you could get better,” he says. Neither especially tall nor agile, Slovic was known for his prowess away from the rim draining long-range baskets, and landed a scholarship to local powerhouse DePaul University. Finding himself benched for much of his two-year collegiate basketball career, he transferred to Stanford to double down on his studies.

EUGENE SALON

Founded by former UO professor Paul Hoffman in 1960 to promote fundamental research into human behavior, the Oregon Research Institute (ORI) became a magnet for a who’s-who of luminaries in the nascent field of judgment and decision-making in the 1960s and ’70s. Besides Slovic, it attracted researchers such as Lewis Goldberg, Sarah Lichtenstein, Robin Dawes, Baruch Fischhoff, and, on sabbatical from Jerusalem’s Hebrew University, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. Kahneman would win the 2002 Nobel Prize in economics for his work with Tversky, who died in 1996. Much of their best-known work was done during their 1971–72 sojourn in Eugene. And, in his bestseller Thinking Fast and Slow about his work with Tversky, Kahneman described the year at ORI as the “most productive” of their intellectual partnership. Slovic, a friend and collaborator, was instrumental in bringing them there. Far from the Olympian figures they might appear today (last year Michael Lewis published an account of their collaboration, The Undoing Project), to Slovic’s eldest son Scott, Kahneman and Tversky were just two rambunctious dinner guests who regaled their hosts with stories and, in the case of the competitive and athletic Tversky, challenged him and his brother to sprinting contests on the Spencer Butte junior high running track. When Slovic, Lichtenstein, and Fischhoff split from ORI in 1976 to create Decision Research, they strove to replicate its collegial atmosphere, says Slovic. “We wanted an organization in the same mold—a small family of researchers following their intellectual passions.”

—By Stephen Phillips

Stephen Phillips is a writer in Portland. His work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the San Francisco Chronicle, the Financial Times, Times Higher Education and the South China Morning Post as well as on the Atlantic’s website and NPR’s The Salt.