The night of the civil war basketball game in early January of this year, I put my phone on silent, scared of the vulnerability of putting months of work in the public eye. I steeled myself against the temptation to check my texts and Twitter notifications. I focused on dicing bell peppers, distracting myself by hosting a dinner party so I wouldn’t have to think about the impending feedback. I knew the project was finally out of our hands. It was up to the world to decide how it felt about Reset the Code.

As one of 18 students who created Reset the Code, I was nervous about how this short-timeline, high-stakes project would be received. The initiative was created to respond to rising tensions and a disrespect for difference, and to encourage students to speak out against intolerance. Given the personal nature of the work, I worried about my team members. How would they feel if they were criticized for work borne from such an emotional process?

When dinner was done, I turned my phone on. My iMessage was flooded with photos of our logo on screens at Matthew Knight Arena, links to Pac-12 coverage of the campaign, photos of sportscaster Bill Walton holding up a tie-dye shirt with our logo, and supportive messages from strangers online. I was overwhelmed.

***

Our team was motivated to create Reset the Code after several hateful events roiled the University of Oregon during fall term. In October, UO law professor Nancy Shurtz wore blackface at an off-campus Halloween party with students. The community drew sides, with hundreds signing a petition defending Shurtz’s free speech rights, 23 of her colleagues calling for her resignation, and the university launching a full investigation. The controversy shook our community, spawning outrage, fear, and classroom debates that left some students more afraid of their peers’ willingness to justify racism than of the incident itself.

Immediately following the election, anxieties spiked again. The morning of November 9, my normally composed media theory class sat in a circle and cried as some people recounted the words that had been screamed at them the night before. Some were told to “go back to where you came from,” and others were called “faggot.” These words hit everyone, even those who had staunchly defended the free speech of Shurtz a week before.

Soon after, a UO student captured a video of three middle school students in blackface outside a Black Student Union meeting. It went viral, leading to the apprehension of the suspects. Reset the Code team member Raquel Ortega said, “I didn’t feel the safest. Those coming weeks brought out the worst and best of people on campus.” The Black Student Union organized a rally on November 11 that drew an enormous crowd and spoke to the overwhelming emotions and desire—held by so many on campus—to create change.

In the wake of these events, School of Journalism and Communication faculty advisor Tom McDonnell gathered students from Allen Hall Advertising, a student-run ad agency. We were accustomed to doing work for local clients, but this time, McDonnell explained, we would be launching a different kind of campaign. He turned the floor over to Brandon Montes-Nguyen, who argued that as communicators, we had a chance to use our skills for the good of the community. We had no idea how to tackle such large issues, but he urged us to try. “What prompted me to do something was that I was genuinely scared,” Montes Nguyen says. “I couldn’t sleep and I felt like I needed to make a difference somehow.”

Our team began brainstorming ideas. Not a single one of our early meetings was shorter than three hours. In working together, our project found its heart.

The diversity of identities and experiences on our team led to intense brainstorming. People had experienced marginalization in distinct ways, which made for an array of perspectives on important issues. We talked about hate and power. We talked about history. We talked about what it meant to be Black, gay, first generation, and scared about the sentiment on campus.

We decided to focus our campaign on those who keep silent—the person who finds blackface heinous yet doesn’t say anything when their friend describes someone as “ghetto,” or the person who is outraged to hear about harassment toward a same-sex couple but sits in silence when someone calls a movie “gay.” They don’t realize how their complacency and silence creates an environment where a hateful few feel emboldened to act unacceptably.

Sonali Sampat, a member of the Reset team, commented that as a woman of color on campus, it is “important that students who belong to marginalized groups feel valued and cared about by the community.”

It came back to the Golden Rule: Treat others as you would like to be treated, and hold others accountable to do the same.

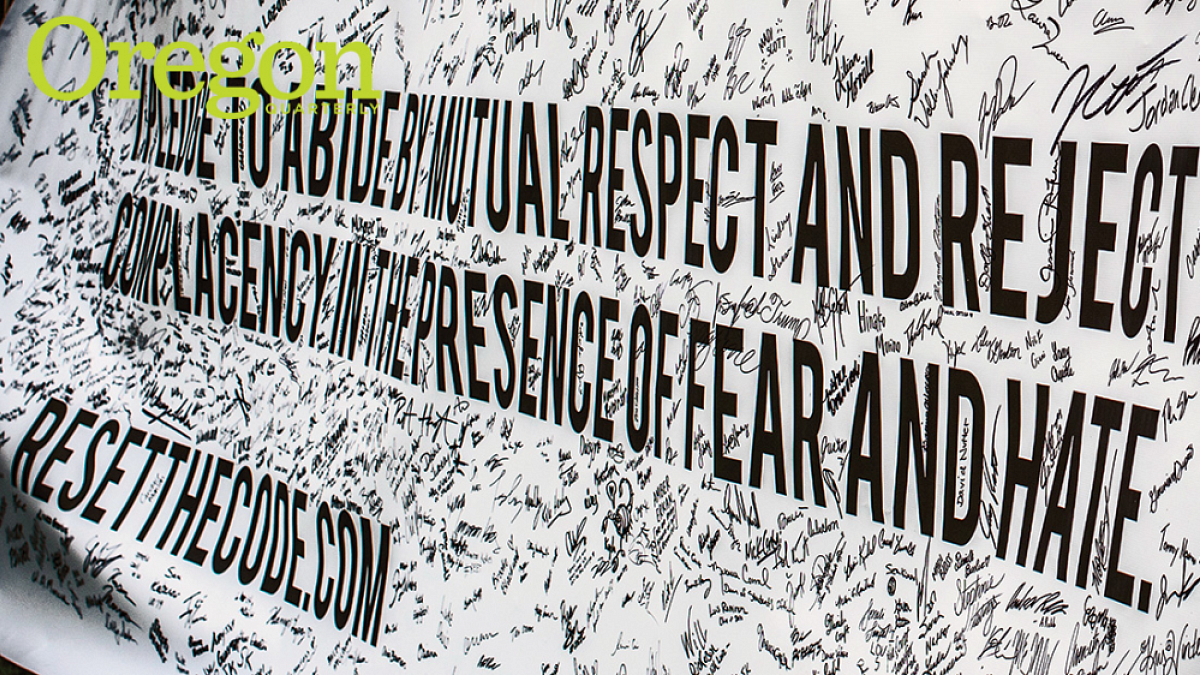

Our creative team started conceptualizing fresh ways to communicate this message. After hours of spouting synonyms, we had it: Reset the Code. The phrase tied together the idea of wiping a slate clean and starting afresh—in this case, returning to an age-old code of conduct shared by cultures around the world. To accompany this moniker, we crafted our own code: “I pledge to abide by mutual respect and reject complacency in the presence of fear and hate.”

The designers camped out for hours in Allen Hall and developed an icon that centers around “95,” the first two digits in a Duck ID “code.” These numbers symbolize a united UO community that allows for a vast number of unique experiences. Circling the numbers is a reset arrow, a reminder that every person, no matter who they are or what numbers make up their Duck ID, has the power to reset the code.

Next, our team had to figure out how to introduce our campaign. Thousands of messages compete for attention every day, so our reveal would need to provoke curiosity and incite buzz. So the symbol couldn’t be ignored, Raquel Ortega suggested we “take away something people would miss: the view from the center of campus.” Using edge-to-edge black coverings, we’d block the view from the windows of the EMU Fishbowl. And on the panels would be this message: “A view unremarkable, until it’s gone. The right to be you, inalienable, until it’s not. Reset the Code.”

We also wanted to build understanding of issues affecting our community. Tylynn Burns came up with “Reset Read,” a video drawn from statements she’d been subjected to as a woman of color. In it, her best friend reads the racist comments back to Tylynn, who reminds her friend that people would be less likely to make these remarks if others discouraged them. To accompany this, team animators created videos showing how to be an “upstander”—someone who speaks up—instead of a bystander.

Finally, the team built outlets for participation. In the “Reset Room,” people could anonymously record their own stories of injustice, mistakes, and intervention. Through the Reset website and social media channels, they could take the pledge online; on campus, they could join the cause by signing a 20-foot banner.

In December, our team members prepared for final exams. But as a group, we focused on a bigger test: getting support for our initiative. We nervously practiced and polished our pitch, working around exam schedules to send team members to various UO offices. Everywhere our team spoke, we gained invaluable allies, picking up 18 partners, including the Division of Equity and Inclusion, the Division of Student Life, and University Communications.

The week following Reset the Code’s roll out, our message spread online to 40 different countries, gained 150,000 Facebook impressions, and earned 70,000 video views. More than 2,000 people took our online pledge with as many or more signing the banner. The Duck Store agreed to sell Reset the Code T-shirts and donate proceeds to the UO Diversity Excellence Scholarship. We kept up the momentum, producing videos, running social accounts, and talking to reporters.

Our campaign was not without detractors, though. Writing in the Emerald, columnist Billy Manggala wrote, “Reset the Code was vaguely telling students to stand up to social injustice, but the campaigns’ discreet strategies didn’t make that completely visible at first.”

After the university’s January 25 decision not to rename Deady Hall, some criticized the campaign for failing to make the changes they wanted. Student Emma Burke tweeted: “Reset the Code a pathetic, transparent attempt at distracting student body from real, institutional injustice w/faux activism.”

Other responses have been supportive. Yue Shen, international student advocate for the Associated Students of the University of Oregon, wrote, “The solidarity with and appreciation of diversity of UO communities could not have been better expressed.”

Self-described Title IX athlete and first-generation American Micki Bessler wrote: “I pledge to make my workplace and town more welcoming to diversity every day.”

That’s why we undertook this challenge. The purpose of Reset the Code is to go beyond words, to help people feel respected and worthy, and to remind others that each one of us has the capacity to be a catalyst for profound change.

—By Hannah Lewman

Hannah Lewman is a third-year student from Portland majoring in advertising and Spanish.