It’s quiet as seven fourth- and fifth-graders from Portland’s Creston Elementary School stand on a grassy bank thick with mud, staring into the slow creek below. A break in the high branches above permits a beam of sunshine to brighten a nose, illuminate a spot on a pink backpack, or reflect off the water with a quick glint.

“Do you see one?” whispers Heather Greene, the resident educator at Aprovecho Sustainability Education Center in Cottage Grove, to the seven sets of eyes that are focused on the water, darting to every flick that might mean movement.

On the banks of the stream, one of the taller boys points, yelling, “There’s one! It’s a newt! I see it!”

“It’s right there!” a small girl in pigtails says, her smile wide and instant, as if she’s just seen a magic trick completed. Then, as the rest of the children assemble, they find the newt, a blurry, small body just below the surface of the water.

In almost every way, what the children have seen really is magic. Newts don’t just conjure themselves up on a sidewalk in Portland; minutes ago, some of the children even doubted such a creature existed.

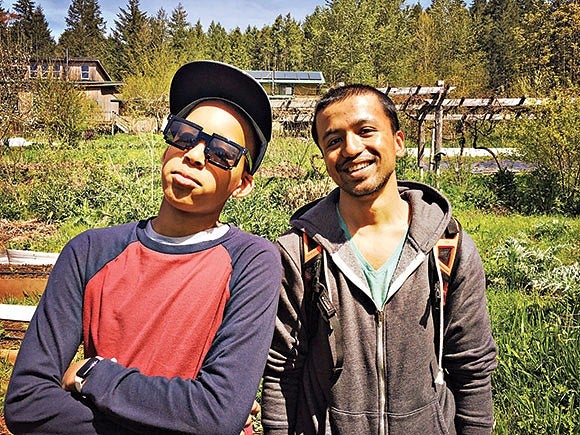

It’s the exact kind of wonder 24-year-old Kevin Frazier, BS ’15, envisioned when he started Passport Oregon, a nonprofit devoted to providing a gateway to nature for city kids who don’t have many opportunities to see what their state has to offer. Now more than a year old, the organization is helping to “close the nature gap,” enabling children to become knowledgeable about the natural environment outside the city.

“We don’t want this to be a normal field trip where you have a worksheet that you have to complete,” Frazier, a native Oregonian, says. “We want this to be a memorable experience where students feel like they are coming home with better friends and a better understanding of Oregon.”

Frazier had the idea for the organization the year after he graduated from Oregon with a degree in economics. He was mentoring a young student named Omar, and Frazier’s girlfriend was about to visit from out of state.

He told Omar about the trips he had planned for her visit, and then asked Omar if he had been to Crater Lake National Park.

“No,” Omar replied.

“Mount Hood?” Frazier asked.

“No,” the boy answered. It was the same for the Columbia Gorge and the coast.

At the time, Frazier was shocked, but has learned since that he shouldn’t have been. With busy working and single parents, some kids don’t have the opportunity to see parts of the state that aren’t close to home.

His family and friends were supportive, and encouraged his vision.

“I have quite an awesome network of friends and family and that’s in large part attributable to the UO; I (knew) folks who had that can-do attitude,” he says.

In addition, Frazier had previously worked in Governor Kate Brown’s office as a scheduler and coordinator. He learned then, he says, that there was no corner of Oregon “that doesn’t have incredibly creative people, incredibly passionate people, and incredible outdoor opportunities.”

Frazier and his team decided to focus on Title I schools, which have a high percentage of children from low-income families. Frazier used his experience of traveling with the governor and talking to a mix of people to lift his project off the ground.

“I met tons of people who understood what was needed to offer more opportunities for the community,” Frazier explains. “And one of those people was Joe Galati.”

Galati, now a member on the board of directors for Passport Oregon, has been an elementary school principal and educator for 29 years in the Portland area.

“I asked, ‘Is this for kids?’” Galati recalls. “And when Kevin nodded, I said, ‘Yes. I will be involved from day one.’”

It was Galati who suggested Creston Elementary, the first school Frazier approached with the idea.

Frazier also secured support from Columbia Sportswear, Café Yumm, Kind, and Embassy Suites, where the kids stop to eat breakfast before every trip.

As a result of its widespread support, Passport Oregon is in the process of buying a van, and has expanded the program to a second Portland cohort at Beaver Acres Elementary School, taking each group on two trips a month. Each venture is free for the participants.

***

At Aprovecho, the trail of students winds up a small hill of native plants as Greene talks to them about how to make a poultice from comfrey, which is growing in a large bush to her right.

One of the younger boys isn’t paying attention. He is staring at his arm, where a caterpillar is inching along in careful, small waves. Soon the other children circle him, watching as the spiny creature travels to the boy’s elbow.

Patrick Miller, BA ’16, is the leader on this trip. Like most of the Passport Oregon staff, he met Frazier while attending the UO, and coordinates all of the trips that involve Creston Elementary. He hangs back for the most part, careful not to interrupt the banter of the children and their interaction with each other.

“I have a lot of experience working with youth and I love exploring Oregon,” he says as the group moves into the garden area. “And this project seemed like a great opportunity to use both those passions.”

The reason this 24-year-old would give up two weekends a month to trek after fourth and fifth graders is obvious when a young boy approaches an artichoke plant, trying for several moments to figure out what it is before he asks Greene.

“It’s a vegetable?” he laughs when he hears her answer. “I thought it was a fish!”

***

In a log house with vaulted ceilings at Aprovecho, beekeeper Paula Mance dons a wide-brimmed white hat with a netted veil.

“All the honeybees in North America were brought here from Europe,” she says as she slips on the rest of her beekeeper’s suit. “They came to Oregon in covered wagons, strapped to the sides.”

She pulls back a cloth covering a square object on a picnic table to reveal a living, buzzing bee hive in a wooden and glass box. The students take a moment to decide whether it’s real or not, and if this humming, moving colony is safe enough to approach.

“Listen to the sound they all make together,” Mance encourages them.

Ranjan, one of the taller boys, moves in first, followed by others who touch the glass, put their ears close to hear the vibrations. Their fingers trail the path of a specific bee; others lean in and watch as the entire hive moves.

The kids will talk about this trip in the days and weeks to come. It is an experience they won’t forget.

As magnificent as this moment is, Kevin Frazier doesn’t want it to stop there.

“The ultimate vision is having Passport Oregon chapters across the state,” he says. “And I don’t think that’s too big of a dream. I think if this has taught me anything, it’s really that there’s nothing a small group can’t do in this world of dedicated people.”

—By Laurie Notaro

Laurie Notaro is a New York Times bestselling author. Her most recent book is Crossing the Horizon.