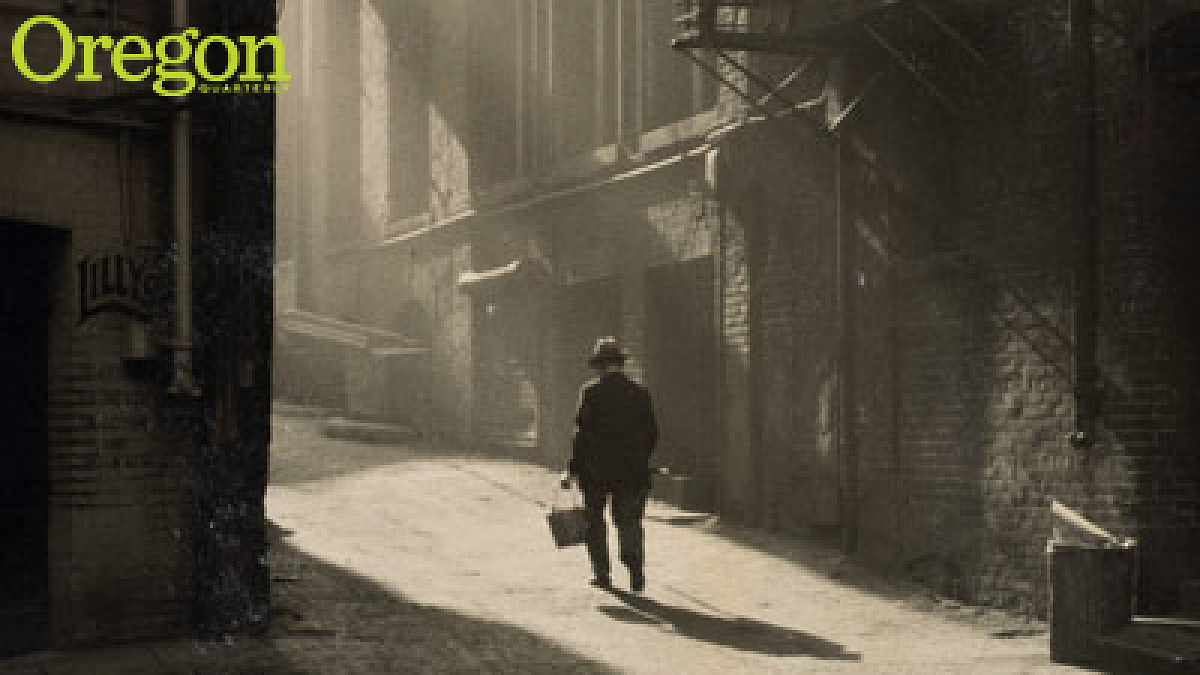

In a vigorous cultural flowering, early twentieth-century immigrant Japanese photographers on the West Coast were remarkably successful in applying to their images an aesthetic brought from their homeland—decorative, suggestive, and poetic. Unfortunately, their success was all too brief, cut short by the events following the attack on Pearl Harbor, including internment and the confiscation of their cameras. The little-known history and art of the Seattle Camera Club is explored by coauthor Nicolette Bromberg, MA '74, MFA '76, in Shadows of a Fleeting World (University of Washington Press, 2011), excerpted below.

My life as a historian has brought me vivid reminders of how partial is the remaining evidence of the whole human past, how casual and how accidental is the survival of its relics.

— Daniel J. Boorstin, Hidden History: Exploring Our Secret Past (1987)

* * *

During the 1920s, many Japanese immigrants on the West Coast found a successful way to both express themselves and to share in the culture of the West by making and exhibiting Pictorial art photography. So many of them were making photographs that they came together to form amateur camera clubs to share their love of the medium. They were amazingly successful. The photographs these immigrant photographers produced were exhibited in both national and international competitions and were included in nearly every book and magazine of popular photography. The artists were so talented and prolific that The American Annual of Photography noted in 1928 that, in various exhibitions, there had been “762 prints hung that were by Japanese photographers in the three [Pacific coast] states in contrast to 237 by non-Japanese photographers from the same region.” These were photographers who, in the words of the editor of the 1928 American Annual of Photography, “put a lasting mark on photography in this country, the repercussions of which are echoing throughout the world.”

Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle, in particular, had large and active camera clubs regularly producing and exhibiting work—yet a few decades later, most of this photography was lost, hidden away, or destroyed. Regrettably, most of the achievements of these enthusiastic and talented Japanese camera club members faded into obscurity, in part hastened by World War II and the internment of West Coast Japanese American citizens. After the war and for many decades later, their work was relatively unknown, as were their achievements. . .

But in the 1920s, Pictorial photography was a perfect fit for the Seattle Camera Club’s Japanese Americans, with its emphasis on nature and emotion and presenting the photograph as art. It has been suggested that, for these immigrants, photography was a convenient way of maintaining their cultural heritage of Japanese arts and aesthetics. They came from a culture that prized art and design in daily life. As Boye De Mente noted in Elements of Japanese Design, “There is no other culture in which design and quality have played such a significant role in the day-to-day life of the people.”

. . . Pictorialism has been defined as “the conscious attempt to turn beautiful objects and experiences into beautiful images.” This was the avant-garde style of its time that developed as photographers tried to gain acceptance of photography as an art form in the early part of the twentieth century. It often involved darkroom manipulation to make the work look more like “art.” However, by the time the Japanese photographers came to it, the emphasis had changed to less manipulation and more expression; and many of them did not print their own work or do darkroom manipulation. Their ideas were visualized in the camera rather than in the darkroom. They took the Pictorial ideas of expression of beauty and emotion and blended it with characteristic elements of Japanese art—use of patterns, flat surfaces, and lack of perspective. These Japanese American photographers were not seeking to be on the cutting edge of photography but found that the emotional and personal nature of Pictorial photography suited what they wanted to express about the world in their art. Indeed, by the 1920s, the Modernist “straight” photography movement, with its emphasis on sharp, clear forms and direct documentation of the subject, was already on its way to overshadowing Pictorialism.

[Key camera club figure Dr. Kyo] Koike discussed his ideas on why he saw Pictorial photography as an art in “Why I Am a Pictorial Photographer,” published in the September 1928 issue of Photo-Era:

“Some think pictorial photography is not a species of art; but I hold another view. Some compare photography with painting pictures; but I think pictorial photography has its own standing, somewhat different from that of painting . . . I read a few photographic books and magazines to learn something about compositions; but it is certain my idea is based on Oriental tendency, much influenced by the Japanese literature and pictures to which I am accustomed. I understand Japanese poems; and I think pictorial photography should not be an imitation of paintings, but it should contain a feeling similar to that of poems.”

In “The Characteristics of Japanese Art,” written by Hoshin Kuroda and translated by Koike, the author writes that while Western art focuses on “human life,” nature is more often the subject of Japanese art. The Japanese artist uses nature in an “idealistic” rather than realistic way: “Accordingly, the Japanese picture is not a real sketch, but is an ideal image of nature.” . . . Koike explained [in his “Pictorial Photography from a Japanese Standpoint” that to] “understand Japanese art, therefore you must shut your eyes and go far away to the slumber land where imagination governs the whole.” Koike saw himself as bringing the poetic “reverberation” from his Japanese culture together with the Western ideas of photography as an art to create his artistic sensibility.

Koike’s work was intimate and subtle poetry, whether it was a photograph of a muddy track through the woods or a tree in the snow that hinted of the soft sound of snow falling. His images are quiet and thoughtful, with the slightly soft focus and matt-surface photographic paper helping to make them experiences rather than documents. It was said of Koike’s work, “Our eyes are soothed by the gentle textural softness of snow; a shimmering surface of water becomes a moment of experience rather than a vision . . . for him photography was not self expression of ego, but it was an expression of a desire to gain quietude in himself, a way to convey the echo of his inner calling.” . . .

The legacy of Japanese culture meant that a sense of harmony was important in these Japanese Americans’ work and that the decorative styles of bold shapes and flat, two-dimensional patterns and shadows were also common characteristics. The name of the Seattle Camera Club’s journal, Notan, and the Japanese idea of this term was a key part of their work. Arthur Wesley Dow defined this as “darks and lights in harmonic relations,” which for the Pictorial photographer was the use of the negative space as a design element where the picture space maintains a balance between the dark and light elements. Koike explained in an article about the club in the November 13, 1925, Photo-Era, “We Japanese must, of course, work within the limit of Japanese ideas, and our art is decorative, suggestive and poetic. . . . Most of us have still to learn how to fill the picture space with a pleasing combination of light and shade, and telling but little. Suggest a story that fills our picture space with meaning, and with pleasure to the beholder. If one may add to this a ‘telling’ placement of light and dark, perhaps that is as near as I can get to what I have in mind as Notan.”

The Seattle Camera Club members not only loved photography, they also loved their adopted city. Seattle was a good place for creative Japanese immigrants who were interested in Pictorial photography. There was a large Japanese community for support and there were physical similarities to Japan in the landscape. Mount Rainier towers over the city and Mount Saint Helens farther south, then with its perfect ice-cream cone shape, was commonly called the Mount Fuji of the West.