There’s a stately white structure in downtown Portland that once held the honor of being Oregon’s tallest building. It’s modest by today’s standards, dwarfed as it is by the marvels of glass and steel that have risen around it in the 101 years since its completion. But if you stand on the northwest corner of Fifth Avenue and Stark Street and look up, you can still see the large black letters painted proudly on its north side: “YEON BLDG.”

This is the story of an architect named Yeon (pronounced “yawn”), and the way he forever changed the nature of architecture in the Northwest, not to mention architectural education at the University of Oregon. This Yeon, however, never built a skyscraper, and his name never adorned a downtown façade. He never completed architecture school, yet his work is influencing a new generation of architecture students. This is the story of the son of the Yeon Building’s namesake, and a far more intimate Portland edifice: a private home tucked away among the firs in a quiet neighborhood in the West Hills. It’s a story about respecting nature and taking bold chances, and about inspiring the young architects of a new century to do the same. And it’s the story of how a small house 112 miles from Eugene came to be a part of the University of Oregon campus.

• • •

In the late nineteenth century, decades before the skyscraper bearing his name was erected, a French-Canadian laborer named Jean Baptiste Yeon (later to be called John B. Yeon) moved west to work in Astoria’s booming lumber camps. In what his son later described as “Horatio Alger fashion,” John B. became a prominent timber magnate, using his wealth to invest in Portland real estate and eventually to finance the construction of that fifteen-story white skyscraper. He maintained a lifelong fascination with building modern roads across Oregon, and served as county road master of the (now historic) Columbia River Highway, overseeing construction of the country’s first scenic highway, which stretches seventy-five miles from Troutdale to The Dalles.

Yeon’s many duties as county road master included appointing architect Edgar Lazarus to supervise construction of the iconic Vista House, which sits atop Crown Point in the Gorge. At the 1918 Vista House dedication ceremony, the elder Yeon’s seven-year-old son, John, participated in the festivities, carrying the tail of the flag. Throughout their childhoods, little John and his three siblings accompanied their father on trips around Oregon, developing an appreciation for the wild loveliness of the landscape from an early age. John later recalled being awed by the “fantastic beauty” of the still-undeveloped Oregon Coast, and appalled by the sight of a section of the Coast Range that had been rapidly logged to supply spruce wood to build airplanes during World War I. In a 1982 interview with Marian Kolisch (a record of which is housed in the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art and served as the source of Yeon’s quotations throughout this story), the architect said, “I was just brokenhearted to see the devastation. I remember just being shocked and horrified by it.” A devotion to respecting natural landscapes would thereafter be one of the defining characteristics of Yeon’s work and life.

After a somewhat miserable stint at a military high school in Indiana (enlivened, notably, by the fact that his campus activities included performing acrobatics on horseback), Yeon took his college entrance exams early and was accepted to Stanford University in 1928. But he only stayed one term before returning north to Oregon, due to his father’s death and the 1929 stock market crash.

A friend of Yeon’s late father, Julius Meier ’95 (son of the founder of Meier and Frank department store), got him a job with a prominent architectural firm in New York. Yeon moved east in 1930, working during the day and studying at Columbia University at night. However, this wasn’t exactly a dream situation to Yeon’s mind. “Columbia was excruciatingly boring,” he told Kolisch. “I had to take courses on, you know, how to put water tanks on top of buildings in New York and so on. And I’m afraid I misbehaved very badly. I kept the job but I kept dropping out of classes.” Yeon left New York and returned to Oregon in 1931, long before his schooling was complete. “I was impatient, terribly impatient,” he said. “I had all kinds of things I wanted to accomplish that more formal education wouldn’t [allow].”

Back in Portland, Meier had just been elected governor (the only independent candidate in the state’s history to ever accomplish the feat). The new governor appointed Yeon to Oregon’s State Parks Commission, a nascent entity he charged with the then-novel and politically unpopular task of advocating for funding for state parks. At twenty-one, Yeon was by far the youngest member of the commission. “I don’t know whether Meier knew I was that young or not. I had grown a mustache and tried to look older,” Yeon recalled. “I had an office in the Yeon Building and I guess anybody whose name is John Yeon, and his address is John Yeon, Yeon Building, Portland, Oregon, gets put on various committees.”

Also on the commission was timber tycoon Aubrey Watzek, an outdoorsman and avid mountain climber. “I joined forces with him and we explored,” Yeon said. “I got to many places I wouldn’t have otherwise found. We climbed anything in sight—Mount Hood and Mount Rainier and Mount Olympus and Mount Shuksan and Garibaldi in Canada.” The two regularly went skiing and snowshoeing on Mount Hood with local groups. Yeon grew particularly interested in the notion of establishing a resort on the mountain, and was instrumental in convincing the state’s WPA administrator, E. J. Griffith, that the lodge should be placed to take advantage of the superior skiing at Timberline, rather than being built farther down the mountain, below Government Camp, as originally planned. Although he succeeded in gaining acceptance for his preferred site, Yeon’s modernist design for the building, the effect of which he later described as “sort of like a ruined medieval castle,” was rejected in favor of the classic WPA-era mountain lodge that stands today.

• • •

When Watzek began looking for a new Portland residence for himself and his newly widowed mother, the twenty-six-year-old Yeon took it upon himself to design one for him, “without being asked to. I made a little model of the house and had it drawn,” he said. He even went so far as to select an ideal plot of land, with views of Mount Hood and the Cascades in the distance. Watzek purchased the land, but he was less sure of Yeon’s design. “It just seemed, maybe too original and not conventional enough,” Yeon later told Kolisch. This, after all, was the mid-1930s, when neocolonial and Craftsman-style homes were de rigueur. Uncertain, Watzek consulted two other architects—one more traditional in style, the other perhaps even more modern—before agreeing to Yeon’s plans.

Over the next year, Yeon oversaw the construction of the house, working out of the A. E. Doyle architectural office, then headed by famed Italian-born architect Pietro Belluschi. Yeon, however, still lacked formal credentials as an architect, and was not a member of the Doyle firm outright. This worked to his considerable financial disadvantage, as he would later recall that he earned a grand total of $500 for the Watzek house design.

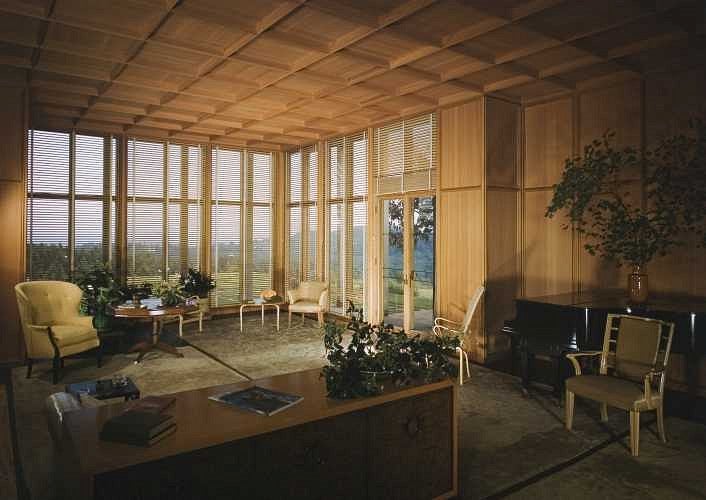

While the financial rewards may have been slight for Yeon, there were significant benefits to having a lumber baron for a client. Clear-grained Douglas fir paneling and massive beams of more than twenty-five feet in length were little trouble to acquire, and their use throughout the house is one of the characteristics of the Northwest regional style for which Yeon would come to be known. His clean lines, wide banks of windows, use of local materials, and graceful relationship between interior and exterior spaces all seem familiar to modern Northwesterners, who have lived for decades in and among homes and buildings based on these design principles. But the Watzek house is that rarest and most fascinating of creations: an artwork that is truly the first of its kind. When it was completed in 1937, it was unlike anything anyone had ever seen before.

Not surprisingly, the world took notice. In 1939, a photograph of the Watzek house, showing the shape of the roof echoing the cone of Mount Hood in the distance, was included in the Museum of Modern Art’s tenth-anniversary exhibit. In 1941, the museum included the Watzek house in an exhibition of cutting-edge American wood houses alongside designs by Frank Lloyd Wright and Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius. International acclaim followed, the attention all the more significant given Yeon’s lack of history, reputation, or even previous presence on the national architectural stage. This, after all, was his very first built design, and he was just twenty-seven years old when it was completed.

• • •

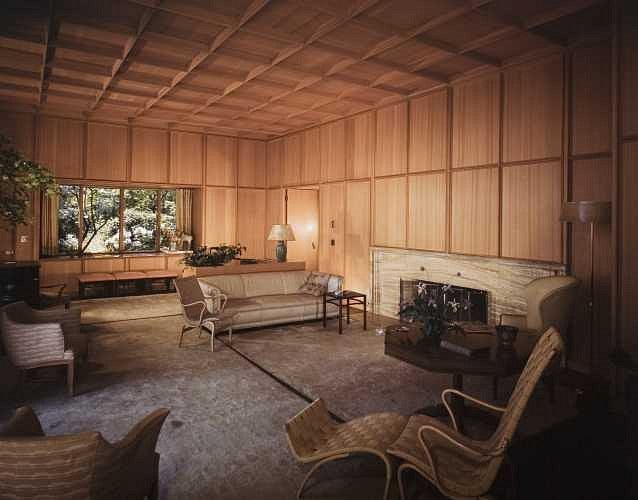

The Watzek house is remarkable, both for its beauty and its level of innovation; it would be a significant achievement for an architect of any age. Yeon’s penchant for stage managing the viewer’s experience down to the last detail is evident from the moment one steps through the door in the silver-grey exterior wall separating the driveway from the house’s courtyard. A winding path follows the border of a fishpond edged by wisteria vines, shepherding the visitor along beneath a low roof to the front door.

Inside the house, Yeon chose to let each room have a different relationship with the world outside, to interact in a variety of ways with the building’s carefully chosen site. Sweeping views of Mount Hood in the distance are featured in the grand, high-ceilinged living room, but the dining room looks out onto a more intimate field of native wildflowers. The master bedroom is framed by trees, many of them planted by Yeon himself.

Yeon wanted the house to gently and constantly reinforce a relationship between interior and exterior spaces, but he was also well aware of the temperamental nature of the Northwest climate. In one of many nods to Portland’s frequently drizzly skies, Yeon ensured that one could move among house, garage, and central courtyard while remaining under cover, able to enjoy the fragrance of the gardens and the sounds of falling rain without getting soaked in the process. Instead of traditional French doors that would open welcomingly onto the back yard during the temperate summer months, but might obscure the view year-round, the architect elected to keep the central windows fixed, placing the doors to the side of the room, allowing summer dinner parties to spill out onto the back lawn while ensuring that the house’s most striking vista remained unspoiled.

Yeon was master of both grand ideas and small details, and craftsmanship of a remarkable quality is evident throughout the house, down to matching grain patterns in the floorboards and the custom moldings that Yeon designed for each room. His detail drawings for the house ran to seventy-five pages, nearly as many as were required for the skyscrapers being erected downtown at the time. He also incorporated numerous built-in storage compartments, pioneered new types of windows and ventilation systems, and custom-designed furniture to compliment the house and the activities that would take place within it. The dining table had room for eight, but two additional tables of the same height and width could be added to either end to extend the length, creating room for more dinner guests. When not in use, these two smaller tables flanked the entrance to the dining room.

Yeon’s multidisciplinary approach to design—blending architecture, furniture design, interior design, engineering, and landscape architecture into a seamless whole—was yet another way his approach differed from that of his contemporaries. Legend has it that he even helped to lay the masonry for the house’s courtyard.

In their 1985 book Frozen Music: A History of Portland Architecture, Gideon Bosker and Lena Lencek describe Yeon as an “exemplary representative of the rare breed of Renaissance men which the modern era of specialization had rendered all but extinct.” It is in this holistic approach to design that Yeon’s work holds such value for students who are able to experience it firsthand. Robert Melnick, director of the John Yeon Center for Architectural Studies at the University, says, “We hope that through studying the house and Yeon’s work, students will gain a broad understanding of the value of true interdisciplinary professional practice.”

• • •

Aubrey Watzek lived in the house his young friend designed for him until his death in 1973. Yeon, who had gone on to design a dozen more houses, the Portland Visitors Information Center, and museum exhibition spaces in three states, purchased the house from Watzek’s estate. Yeon never lived in it himself, however. Richard Louis Brown, Yeon’s close friend and a partner in many of the conservation activities the architect remained devoted to throughout his life, was the house’s second resident. In 1994, when Yeon died at the age of eighty-three, Brown inherited the architecturally significant structure. Deeply dedicated to upholding Yeon’s architectural legacy and ensuring the house would be preserved in perpetuity, Brown approached the University (as well as several other institutions) about his aspirations for the property. During a series of conversations with Brown about the house’s future, Melnick, then dean of the School of Architecture and Allied Arts, found himself in agreement with Brown’s ideas. Less than a year later, in the fall of 1995, Brown officially passed ownership of the Watzek house to the University, thereby establishing the John Yeon Center for Architectural Studies and ensuring that his friend’s work would continue to educate and inspire new generations of architects and designers.

Today, architecture students and professors use the house in many ways. Interior architecture classes have visited to perform materials studies, while other students have worked to document the landscaping. Faculty and staff members, as well as graduate assistants, have constructed preservation and use manuals for the house, guides that are regularly utilized as the seventy-five-year-old structure receives maintenance and repairs. Dozens of books and articles mentioning or focusing on the house have been published and more are under way, including a treatise on Yeon’s legacy of design and preservation by Leland M. Roth, professor emeritus and former Marion Dean Ross Distinguished Chair in Architectural History.

Perhaps most important, though, is that the house’s design can be fully experienced by the students who visit, rather than studied in slides and textbooks. “You can’t replace going on a site visit,” says graduate architecture student Amanda Morgan. “There’s just nothing quite like it.” Morgan notes that while technology has increased students’ access to images and even three-dimensional renderings of significant properties from all over the world, architecture’s experiential nature means that nothing compares to actually walking through the front door and being physically present in the space. After visiting the Watzek house, she says, several key design elements made “more sense to me, in their context, than they ever had in any of the slides.” She notes that the inspiration to be drawn from visiting a well-designed house is critical for young architects like her. “There’s always something you can take away from a great building.”

Today, the University is owner and caretaker of three Yeon-designed properties, a significant portion of the architect’s total output. With fewer than twenty completed architectural works to his name, Yeon once said, “I often think I have probably more reputation based on fewer works than anybody I can think of in the history of architecture.” Besides the Watzek house, the University has received gifts of Yeon’s final built design, the George and Margaret Cottrell house, located across the street from the Watzek House and currently used to provide housing for architecture faculty members teaching in Portland; and the Shire, Yeon’s landscaped property in the Columbia River Gorge, now the centerpiece of the John Yeon Preserve for Landscape Studies, a seventy-five-acre waterfront site directly across from Multnomah Falls.

Melnick, director of the John Yeon Center, says that in coming years the properties will be used as the focal point for more fellowships, symposia, and publications that inspire new scholarship and cutting-edge thinking about architecture, landscape, heritage conservation, planning, and design challenges of the twenty-first century. Melnick notes that the Watzek house provides an ideal venue to grapple with both the philosophical and deeply practical aspects of preservation, planning, regionalism, climate, and climate change, all ideas that will shape the careers of today’s students and the future of the profession. And thanks to its designation as Oregon’s newest National Historic Landmark, an honor it officially received on July 25, 2011, the Watzek house, and through it Yeon’s creative spirit, boldness, and dedication to the Northwest landscape he loved so much, will continue to inspire students and professionals at the University and beyond for many years to come.

—By Mindy Moreland

Mindy Moreland, MS ’08, is the Portland contributing editor of Oregon Quarterly.

Watzek House Tours

As part of the Yeon Center’s mission to share Yeon’s work with the public, University alumni and friends are invited to participate in a series of tours of the Watzek house and the Shire this summer. Details and registration information can be found by visiting www.aaa.uoregon.edu/tours.

Watzek House Tours

June 30 | July 28 | August 26 | September 22

Three ninety-minute tours are available each day, at 10:00 a.m., 1:00 p.m., and 3:00 p.m. Tours are limited to twelve people. Tickets are $15.

The Shire Tour

September 23, 10:00 A.M.

This three-hour event includes a ninety-minute guided tour and ninety minutes to enjoy a BYO picnic on the grounds. Registration is limited to twenty people. Tickets are $15.

Learn more about John Yeon and the John Yeon Center by visiting www.aaa.uoregon.edu/institutes/yeon.