When Jack Joyce '64 cofounded Rogue Ales in 1988 alongside his University of Oregon fraternity brother Bob Woodell, the duo never could have envisioned the rise of craft beer. "What college buddies don't fantasize about opening a bar together? That's where our minds were," Joyce says. In Rogue's rookie year, the craft brewery made about 50 barrels of its two original brews, Amber and Gold. In those days, that modest output immediately positioned Rogue among the nation's 25 largest craft brewers. A quarter-century later, with annual production now topping 100,000 barrels, Newport-based Rogue remains just inside the top 25.

"Go figure," says an amused Joyce.

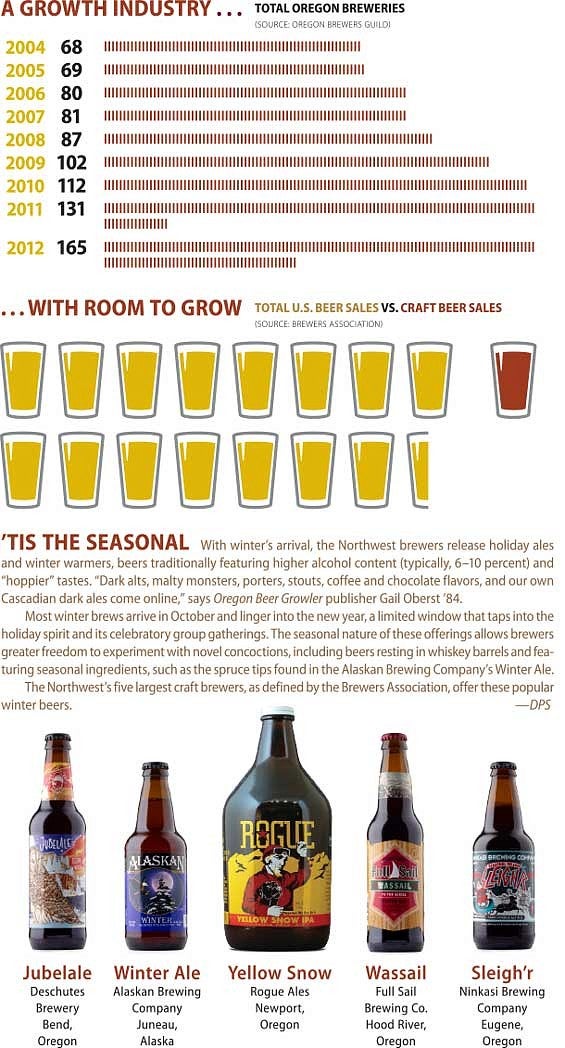

As of June 2013, the United States hosted nearly 2,500 craft breweries, according to the Brewers Association trade group. That's a 25 percent jump from just two years earlier and a number not seen since the pre-Prohibition years of the late 19th century.

The Brewers Association defines an American craft brewer as small and independent, producing fewer than 6 million barrels annually, and having no more than 25 percent of the brewery owned or controlled by an alcoholic beverage industry member not itself a craft brewer.

"There's a much different understanding of craft beer today than even 10 years ago, let alone 20," says Jamie Floyd '94, founding brewer of the Ninkasi Brewing Company in Eugene.

And it's the Pacific Northwest—and many UO graduates—helping to lead the charge. Just one decade ago, Oregon claimed fewer than 70 breweries, according to the Oregon Brewers Guild. Today, the state hosts 175 brewing facilities in 59 cities, while Portland, with 51 breweries inside its city limits, boasts more breweries than any city in the world.

Oregon's love for craft beer goes way back, beginning in 1862 when German immigrant Henry Weinhard opened his namesake brewery in Portland. Since then, Northwest brewers have used the region's bountiful hops, barley, and water to produce innovative beers.

"Oregon brewers have a history of standing where the ocean and the land meet and looking forward," Floyd says.

Craft breweries like Rogue, Deschutes, and Widmer Brothers, a brewery cofounded in 1984 by Kurt Widmer '78, sparked a late 20th century surge and inspired a plethora of regional players, such as Oakshire Brewing, founded by brothers Jeff '99 and Chris Althouse, and Worthy Brewing, where Chad Kennedy, MS '98, serves as brewmaster.

Fiercely loyal to local options and open to experimentation, particularly when it comes to food and beverages, the state's residents have embraced craft beer. The Oregon Brewers Guild reports that residents consumed nearly 2.8 million barrels of beer (700 million pints or 924 million 12-ounce bottles) in 2012, nearly half of which was brewed within the state. Oregonians are sharing their favorite beers with others, attending brewers' open houses and tastings, and flocking to events such as the annual Oregon Brewers Festival in downtown Portland, which attracted a record 85,000 guests in July.

"This makes for a rich foundation for craft beer to grow," says Gail Oberst '84, the publisher ofOregon Beer Growler, a monthly publication that tracks the state's craft beer scene.

But is it too much too fast?

From 2011 to 2012, the state added 34 breweries. This rapid growth has awakened old concerns about future prospects for the developing industry.

Rogue's Jack Joyce fears craft beer could soon suffer if the supply of technical expertise and experience doesn't catch up with brewery demands. "This is not a kit," he says. "To make great beer, you need a palate. And that's part gift and part experience and not something that can be automated."

Another concern: The multinational brewing conglomerates have jumped on craft's bandwagon. They've plucked talented brewmasters from upstart enterprises, acquired small breweries, and emulated craft's look with artistic, edgy packaging. Craft beer purists now worry that the category could become watered down, that this trend could undermine what is now a vital and innovative industry.

Jamie Floyd of Ninkasi Brewing and many fellow beer enthusiasts, however, stand undeterred. It's a new era with a different consumer and a more focused industry, he says. "Years ago when people weren't pleased with a craft beer they tried, they condemned the whole category," Floyd explains. "Today, if they don't like one craft beer, they try another."

That shifting dynamic sparks optimism in folks like Oberst, who foresees no slowdown in craft's future. "I only see it getting more gentrified," she says—"more new breweries making for a richer experience for consumers."

—By Daniel P. Smith