‘Saber’ no more: A giant prehistoric salmon had spike teeth

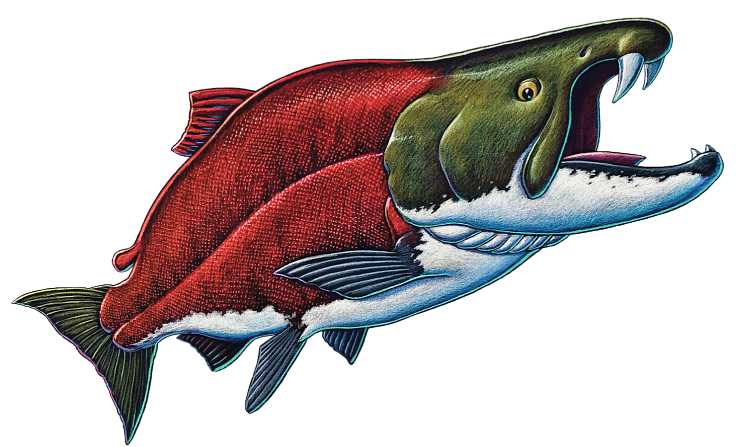

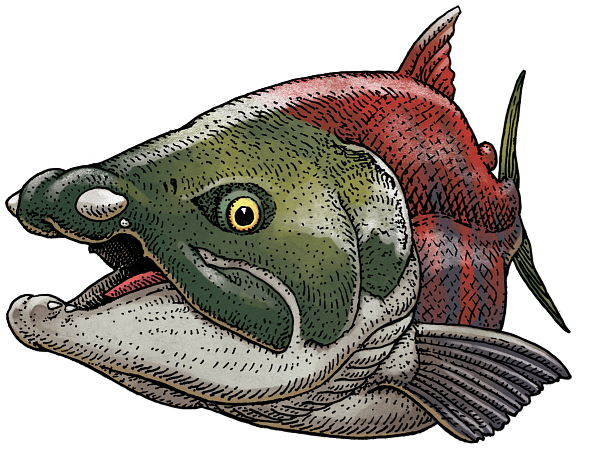

Say goodbye to the saber-tooth salmon, and say hello to the spike-tooth salmon. Don’t be sad. The saber-tooth salmon hasn’t lost any of its fearsome appeal. But new research, including some striking illustrations by paleoartist Ray Troll, has revealed something new about its prehistoric piscine anatomy: The giant salmon Oncorhynchus rastrosus had a pair of spiked teeth that protruded straight out of the side of its skull, instead of the downward-pointing teeth scientists formerly thought it had.

“I’m delighted that we have been able to put a new face on the giant spike-tooth salmon, bringing knowledge from the field in Oregon to the world,” said Edward Davis, an associate professor of earth sciences at the University of Oregon and director of the Condon Fossil Collection at the UO’s Museum of Natural and Cultural History.

“This project highlights the international scope of collaborations at the UO and Museum of Natural and Cultural History,” he said, “as well as illustrating the way local Oregon discoveries can have implications for understanding evolution and the consequences of climate change on the global scale.”

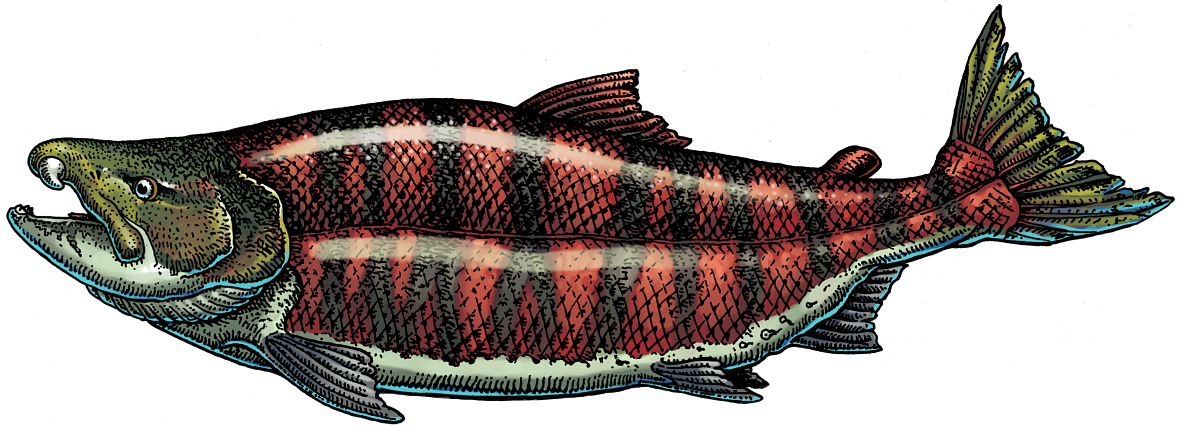

Growing to more than 8½ feet long on average, the prehistoric fish were the largest salmonid to ever exist, swimming the waterways of what is now the Pacific Northwest more than 5 million years ago. The modern Chinook salmon, or Oncorhynchus tshawytscha, the largest living member of the genus Oncorhynchus, tops out at about 5 feet. Hucho taimen, or the Siberian salmon, is the world’s largest living salmonid. It can only grow to about 6 feet long.

When the original O. rastrosus fossil was discovered and described in the 1970s, its skull had been crushed from above by the weight of time. Paleontologists could see it had two large teeth on the upper jaw, unique to its species, but the upper jawbones were disconnected from the rest of the skull.

They hypothesized, based on current salmon anatomy and other animals of the era, that its two fangs pointed down, much like a Smilodon, or saber-tooth cat. Researchers originally dubbed the fish a "saber-tooth salmon."

In 2014, paleontologists uncovered additional O. rastrosus fossils from the same area that had jaws and teeth intact. Those well-preserved fossils revealed that the saber-tooth nickname was a misnomer. The salmonid’s upper teeth pointed laterally out of the sides of its face, more like tusks or spikes than saber teeth.

Researchers at the UO’s Museum of Natural and Cultural History, Oregon State University, and Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine have thoroughly investigated the updated fossils. Their paper, published this week in the journal PLOS ONE, describes the spike-tooth salmon in more depth than ever before.

“We have known since the 1970s that these extinct salmon from Central Oregon were the largest members to ever live,” said Kerin Claeson, lead author and professor of anatomy at Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine. “However, more than a half a century later, new discoveries told us that these were probably not ‘gentle giants’ on account of massive spikes at the tip of their snouts.”

The researchers believe the spikes, about 2 inches long and slightly curved, were useful when they swam upstream to spawn. That journey has always been perilous, and weapons on the side of the spike-tooth salmon’s face could have come in handy.

“Along the way the spikes would have been useful to defend against predators, compete against other salmon, ultimately build the nests where they would incubate their eggs, and then fight off any rival salmon who wanted to use their nests instead,” Claeson said.

The researchers also found evidence of sexual dimorphism, meaning differences in anatomy between males and females of the species. For example, the front of the skull where the upper jawbones attach comes to a sharper point in males than in females.

“However, we stress that females and males alike possessed the enormous, tusk-like teeth,” said Brian Sidlauskas, a professor and curator of fishes at Oregon State University and a co-author of the paper. “Therefore, the sexes were equally fearsome.”

The anatomy of fish from 5 million years ago can give us insight into modern ecosystems in the Pacific Northwest.

“These majestic animals went extinct with cooling oceans millions of years ago,” said Davis, the UO professor, “and their biology tells us about the habitats we might see in the next hundred years if global climate change goes unchecked and brings us back to the warm oceans of the heyday of the giant spike-tooth salmon.”

A model of the spike-tooth salmon by paleoartist Gary Staab is currently on display at the Museum of Natural and Cultural History, with its spike teeth visible. The mural behind the model, which was painted right before the 2014 discovery of intact spike-tooth salmon skulls, still has saber-teeth, an homage to science’s ever-evolving understanding of life on Earth.

— Story by Lexie Briggs

— Illustrations by Ray Troll

— Animation by Chris Larsen

— Layout design by Paul Kozik and Tim Beltran

— Digital illustration coloring by Grace Freeman