Science plus a good story spurs action on youth concussions

UO researchers work with parents to find the best ways to explain the dangers and reduce kids’ risk

Engaging personal stories combined with scientific information can inspire trust and a motivation to reduce the risk of concussions, a significant issue in youth athletics, according to a new study by two University of Oregon researchers.

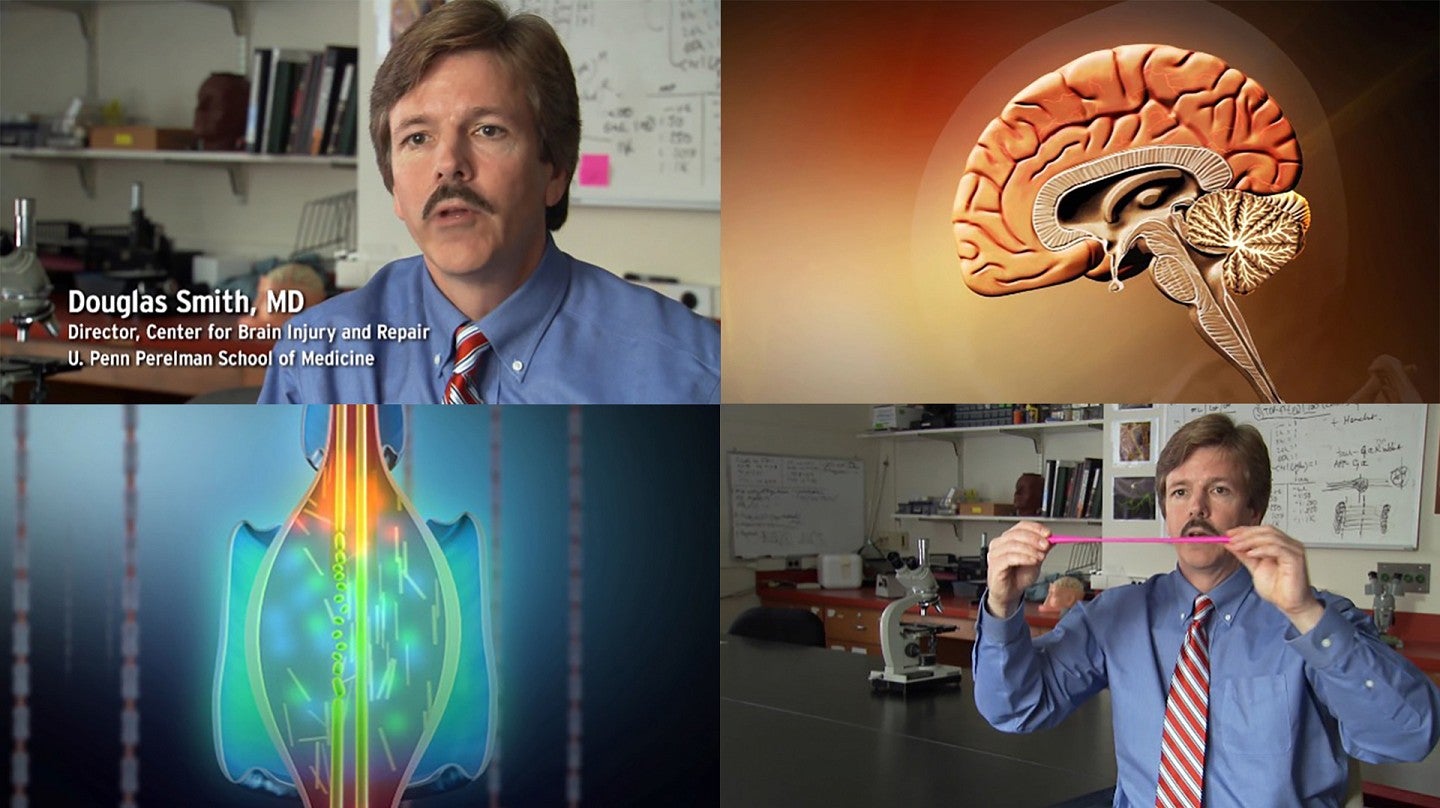

In experiments conducted with parents of 10- to 17-year-old students, Jesse Abdenour and Autumn Shafer, associate professors in the School of Journalism and Communication, compared responses to six different videos about students who had received concussions playing soccer and football. The more parents felt absorbed by the stories, the more they tended to trust the content of the videos, the researchers found.

In addition, the more absorbed parents were by the videos, the more they indicated a willingness to talk with their children about concussions. They also were willing to steer their children toward sports with a lower concussion risk, to monitor their children, and to encourage them to rest after experiencing head trauma.

Abdenour and Shafer reported their results in a paper published in November in the research journal Health Communication.

Previous studies have found that between 1.6 million and 3.8 million sports-related concussions occur in the United States annually. Head trauma affects about 20 percent of adolescents in activities such as football, soccer and cheerleading.

Abdenour, a former journalist, became aware of concussion risk in the course of his participation in boxing.

“I’ve probably had my bell rung and had minor concussions, but I was never diagnosed,” he said.

He boxed competitively as a young man and after dropping out of competition, continued to spar and do workouts. After receiving what he thinks was a concussion in 2017, he recalls experiencing changes in depth perception that affected his ability to drive.

“I had trouble with spatial awareness, judging speed and merging into traffic,” he said. “So that was pretty scary.”

After he learned about the long-term health effects of concussions, he decided to stop sparring altogether. Later, Abdenour became aware that despite well-publicized news stories about concussion in professional football players, surveys showed that many American parents disregard the risk for their children who play sports.

“Many people just disregard the news reports about the link between concussions and long-term damage when it comes to deciding if, as a parent, they want their child to play football,” he said.

Concussion presents a more serious risk than injuries such as a sprained ankle or broken arm, he added. Children who experience head trauma face a potential increase in dementia or other mental harm later in life.

Based on his previous research on trust in journalism, Abdenour wondered if parents’ attitudes stemmed from a lack of trust in news media or in science. To learn about how parents respond to stories about concussion, he teamed up with Shafer, an expert in health communication methods and a parent with school-age children of her own.

“We were especially interested in parents, because more young people (than adults) are exposed to sports concussions,” Shafer said, “and parents tend to make health decisions for teenagers playing sports. We really wanted to do an experiment where we could look at cause and effect, at the effect of these types of concussion narratives and science on parents’ beliefs about concussions and their intention to mitigate harm.”

“Overall, findings indicate that blending concussion narratives with a related science demonstration is more effective at fostering healthy concussion-risk perceptions and mitigation intentions than presenting parents with Science-Only or Narrative-Only messages,” they wrote. “This finding indicates that, even for controversial science topics, if you tell a good story people will trust it and subsequently be more open to scientifically informed perceptions and behavior.”

Great storytelling starts here

Students in the UO School of Journalism and Communication study strategic communications, immersive media, journalism, public relations and more. Undergraduates and graduate students dive into new media and new forms of storytelling using professional-quality equipment and facilities. Click the link below to start writing your own story at the SOJC.