UO scientists update eruption history of Oregon’s South Sister

New research shows the Cascades peak was more volcanically active over a shorter time frame

A hiker’s pack usually gets lighter over time as they plow through trail mix and water, but Annika Dechert likes to joke that hers gets heavier.

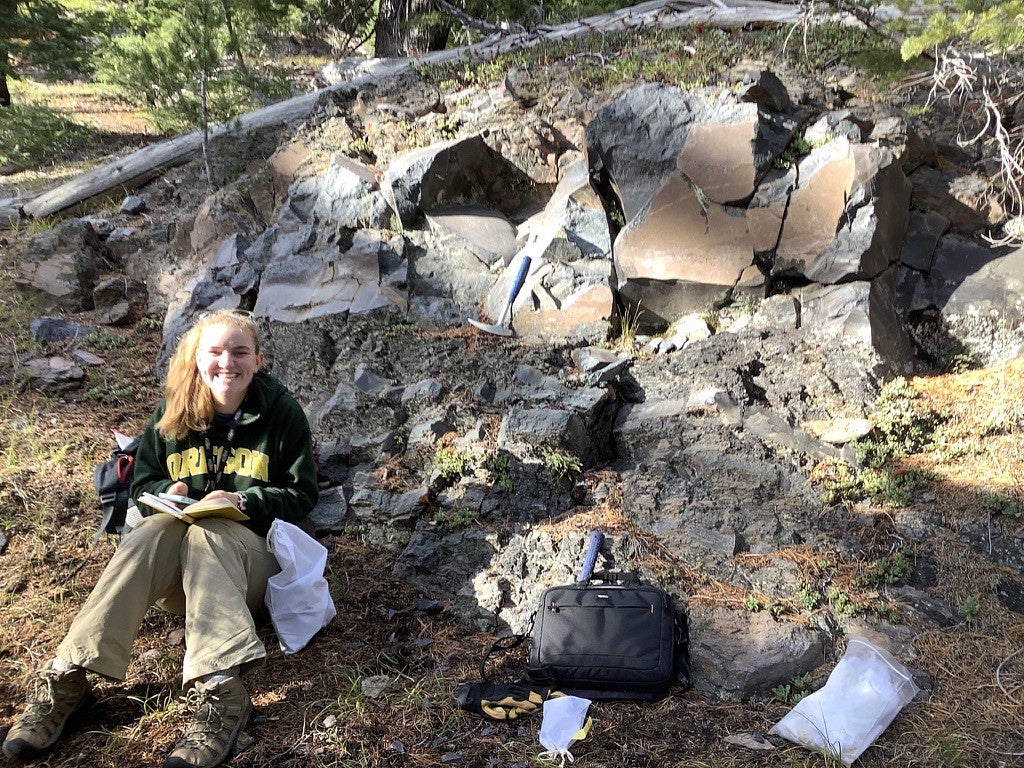

As an earth sciences graduate student at the University of Oregon, she’s picking up clues to the eruption history of South Sister volcano in the Oregon Cascades, helping scientists better understand its possible future risk. Those clues: 10-pound chunks of crystal-studded rocks, ejected during past eruptions spanning 39,000 to 2,000 years ago and hauled off the volcano by Dechert and a team of volcanologists.

South Sister, which sits in a wilderness area popular for outdoor recreation, is classified as a “very high threat” by the United States Geological Survey. By analyzing crystals in volcanic rocks, Dechert and her colleagues have now found that South Sister was historically active with greater intensity over a shorter time window than previously believed. And they’ve shown two distinct periods of eruptions in South Sister’s past that appear to come from different sources.

“Volcanoes sort of have personalities,” said Joe Dufek, the Gwen and Charles Lillis Chair of Volcanology at the University of Oregon, who led the research alongside Dechert and a collaborator at the USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory. “Understanding their past activity gives us a sense of what they might do in the future.”

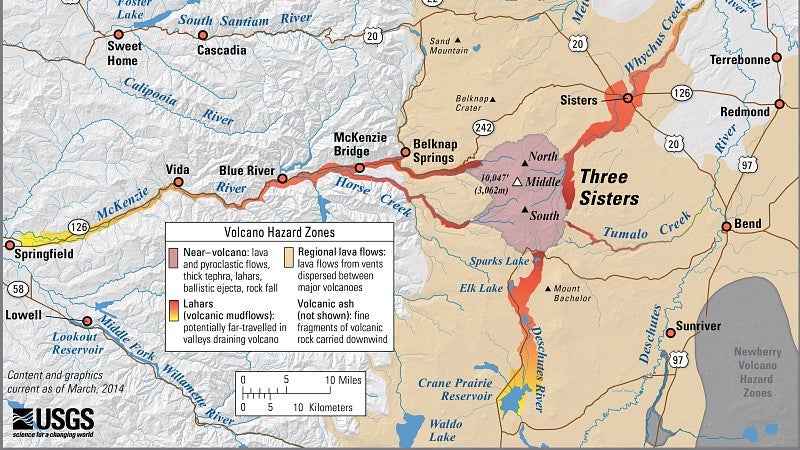

The results of the study will inform the way the USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory draws up hazards maps for Central Oregon and help shape the way scientists think about other similar volcanoes. The research team published their latest findings in August in the journal Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems.

Although South Sister hasn’t erupted for a few thousand years, the USGS still keeps close tabs on it. Since the 1990s scientists have been tracking a magma bulge growing under the volcano, a sign that even though it seems calm, there’s probably activity happening under the surface.

Because it’s situated less than 30 miles from Bend, even a small eruption could put a big hurt on Oregonians. An eruption could send plumes of ash into the sky, making the air hazardous to breathe. Volcanic mudflows could enter nearby rivers, degrading water quality and damaging properties along their banks. Lava flows could present hazards higher on the volcano and might spark wildfires. Landslides or lava flows might close roads or trails.

Understanding the cascading hazards from such events has been the focus of the volcanology cluster at the University of Oregon.

To better understand how South Sister has behaved in the past, Dechert and her colleagues focused on rhyolite, a glassy kind of volcanic rock. Rhyolite produces explosive volcanic eruptions that eject ash, rocks and gas forcefully into the air, as opposed to eruptions that feature lava slowly pouring out. It’s relatively rare in this part of the Cascades, but it’s a prominent part of South Sister’s geology.

On field expeditions over several summers, Dechert and her team hiked to South Sister with big backpacks and a sledgehammer and chiseled out rhyolite samples from various lava flows around the volcano. (The researchers have secured permits to collect samples; rock collecting is generally prohibited in wilderness areas.) Their sampling sites represent eight different eruptions of the volcano, spanning tens of thousands of years.

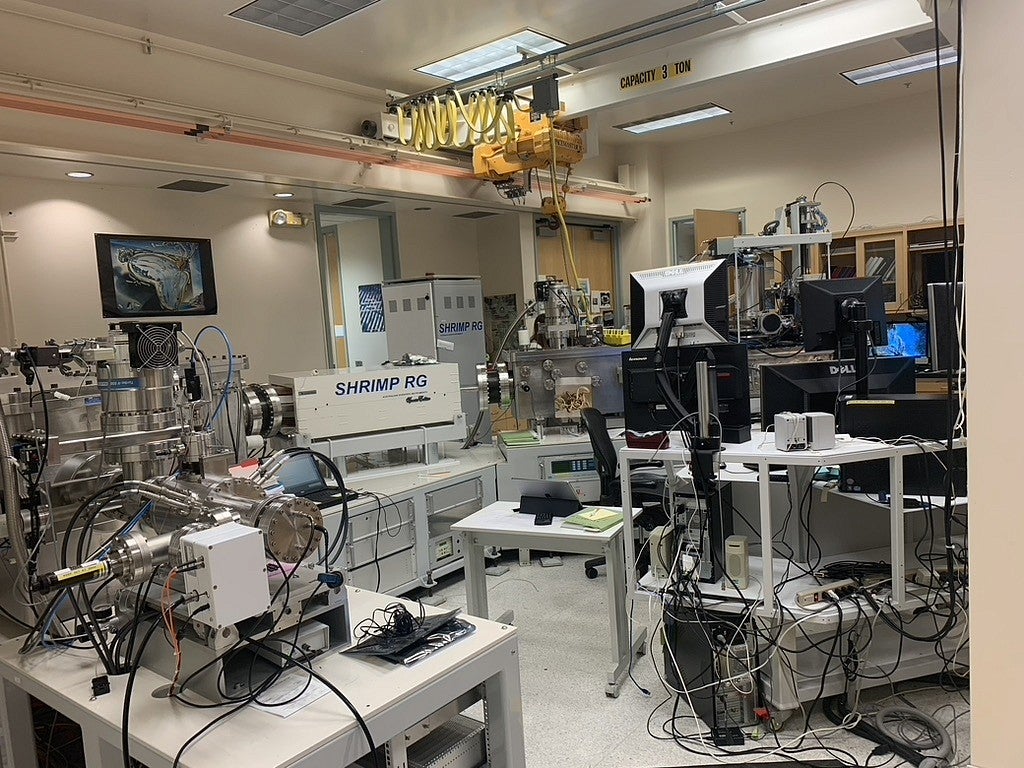

Back in civilization, Dechert brought crystals from the rocks to a specialized lab at Stanford University that estimates the ages of the different samples and when they erupted from the volcano. Zircon crystals embedded in rhyolite contain uranium that decays into lead at a set rate over time, so scientists use the crystals as tiny rock clocks.

All the rhyolites that erupted from South Sister during its earlier period of activity came out over a span of 15,000 years, rather than 27,000 years, the new analysis found. The oldest eruption from that period happened around 39,000 years ago during the Pleistocene era — more than 10,000 years later than past data showed.

With the same amount of volcanic activity happening over a shorter period of time, South Sister’s past eruptions were more intense than previously believed, the study suggests.

Dechert and her colleagues also found that the Pleistocene eruptions were chemically and physically distinct from another cluster of eruptions that happened around 2,000 years ago. That suggests multiple different magma reservoirs in the volcano, capable of producing different kinds of eruptions, Dechert said.

“We can use this updated chronology of the past to inform what might happen in the future,” she said. With the new data giving a better idea of how often South Sister erupted and how much material came out of it at different intervals, “we can use those ideas to think about what might happen in the future if this more recent eruptive sequence were to continue.”

The new dates also help confirm when South Sister became active compared to neighboring volcanoes Middle Sister and North Sister. Geologists have gone back and forth on this question, depending on what data source they use. The newest data suggest that South Sister started erupting after Middle Sister, but the two volcanos had an overlapping period of activity.

The study is part of a bigger ongoing research project piecing together South Sister’s history. Now the research team is using instruments that detect micro-fluctuations in gravity strength to map possible magma chambers beneath South Sister. The different density of magma compared to solid rock causes very, very slight changes in the strength of earth’s gravitational field in different places. In combination with the zircon dates revealing the age of past eruptions, researchers are getting an even better picture of what South Sister might be capable of down the road.

“The leading hypotheses suggest there’s magma under the Three Sisters, and we’re trying to confirm this with geophysical imaging,” Dechert said.

Still, Dechert emphasizes that that any eruption of South Sister — also known by its Indigenous name, Klah Klahne — would be preceded by ample warning signs. Hikers can continue to safely enjoy the winding trails, abundant wildflowers, sparkling lakes and scenic vistas that have made this part of the Cascades so treasured by humans for many thousands of years.

“This is a beautiful place to explore, and I don’t want to deter people from getting out there,” she said. “Just 2,000 years ago, there was new land being formed. That’s really exciting.”