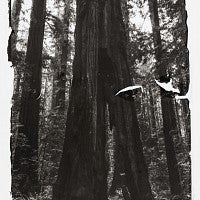

In 2020, historic wildfires burned more than 10.2 million acres across the western U.S. At least 37 lives and tens of thousands of structures were lost. Those traumatic events spurred Eugene artist Sarah Grew to create a series of photographs printed from the charred remains.

For her latest installation of “Ghost Forest,” April 24-May 4 at the LaVerne Krauss Gallery in Lawrence Hall, Grew has teamed up with sound artist Jon Bellona, a senior instructor at the UO’s School of Music and Dance who teaches audio production. "Ghost Forest" is sponsored by the Center for the Study of Women in Society as part of its 50th anniversary and the UO’s Environment Initiative.

“It’s a radical change to add sound,” Grew said. “I think it will add a whole different dimension. This is a meditative space, and we’re working to preserve that. The ‘Ghost Forest’ will hopefully inspire reflections on climate change, fragility and time.

“The photos are lantern slides framed in glass, which is fragile, like the forest. The work portrays forest time, which is different from human time. Trees can live 500 years or more. And photography basically collapses time altogether.”

In Grew’s “Ghost Forest,” visitors move through pairs of cables suspending the photographs and creating a three-dimensional experience. Grew’s carbon prints portray fire’s devastation but also flowers, leaves and other living elements. As they explore the installation, visitors encounter light, shadow, the photographs and each other in changing ways, a more engaged, arresting experience than photos on a wall.

The cables, Grew said, also echo the outline of a tree. The 70 photo trees in the installation symbolize an average of 70,000 wildfires per year in the U.S. over the past decade. Grew added that 90 percent of them were caused by humans and, although the number has been declining, their size, temperature and intensity continue to increase.

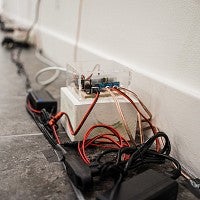

—Sound installation photos by Janelle Rodriguez

Even on a good day, carbon printing isn’t for the faint of heart. Introduced in the mid-19th Century, it is still considered the most permanent photographic printing process. Grew figures, at best, two-thirds of her prints turn out. When it does work, the result is often purposely imperfect, frayed at the edges or dappled by air bubbles, an aesthetic resembling the aftermath of fire. The color of the photos vary depending on which species of tree was the source of the coals she used to grind the carbon powder.

Bellona had the spark for his sound installation project during a drive from Eugene to Santa Cruz, California, when the 2018 Delta Fire forced him to take a four-hour detour along back roads.

“It was apocalyptic, like Mad Max,” Bellona said. “The haze turned the sun blood red. I thought about how sound could play a role in helping us understand the environment. How could listening create a better understanding of our relationship to wildfires?

“Later, I learned that the 2018 Camp Fire, California’s deadliest and most destructive wildfire, moved the length of a football field every few seconds. I thought, ‘How could I sonify this?’”

Bellona built the speakers for his “Wildfire” sound installation using different species of wood: alder, pine, sycamore, myrtle wood and black walnut, all sustainably sourced. The fire sounds sprint across this 48-foot speaker installation at 83 miles per hour, the calculated speed of the Camp Fire.

Bellona and Grew are collaborating on the best way to meld her vision with his sounds in a new space. Inevitably, devastation is part of the exhibit, Grew said. But so is the beauty of nature. Ultimately, her goal is to give visitors hope.

“It’s about fire, but it also tells the story of the forest that hasn’t burned and the forest that’s coming back,” Grew said. “This helps keep people from shutting down. I hope they get a renewed sense of the importance of the land and a reminder of what’s still out there.”

—By Ed Dorsch, University Communications