Mix 19 upper-level undergraduate students from the Robert D. Clark Honors College with five faculty members from biology, physics and literature for 10 weeks and you'll get bread: yeast, rye, wheat, white, sourdough and Russian.

"Bread 101" was offered spring quarter as an experimental colloquium. On the final day, as everyone detailed what they had learned and bread smells filled the classroom, it was clear the course had not been a half-baked idea.

"Learning about bread has expanded my appreciation of the complexity of not only the bread market, but also of the industrial food-production model, in general," said anthropology major Spencer Kales. "It will affect my buying habits, and I will definitely go after locally grown organic foods."

Judith Eisen, professor of biology and part of the teaching team, said the course gave her satisfaction. "I learned it is possible to take something that is mundane, ordinary and taken for granted, like bread, and transform it into something that really engages the interest of students by delving into the underlying science and putting into a social, cultural and political context."

The course, HC441, probed the science and culture of bread and served to raise the interest in the new UO Food Studies Program, where courses are built around nutritional importance and interdisciplinary perspectives drawn from across the liberal arts. Students also studied primary sources on bread-baking and historic propaganda available in the exhibit "Recipe: The Kitchen and Laboratory: 1400-2000" in Knight Library Special Collections. Jennifer Burns Bright, who helped teach Bread 101, and Vera Keller, a historian of science in the Honors College, are curators of the exhibition.

In their own kitchens, students experimented with sourdough starters and their own breads based on historic recipes. To educate students on the properties of wheat hybrids and bread production, wheat geneticist Steve Jones of the University of Washington visited the class. There also were field trips to Camas Country Mill and Noisette Pastry Kitchen to hear from growers and bakers.

"I learned a lot about how complex and globalized that bread production and flour production are, even in the Willamette Valley," said Nicolette Dent, who graduated in June with a degree in anthropology.

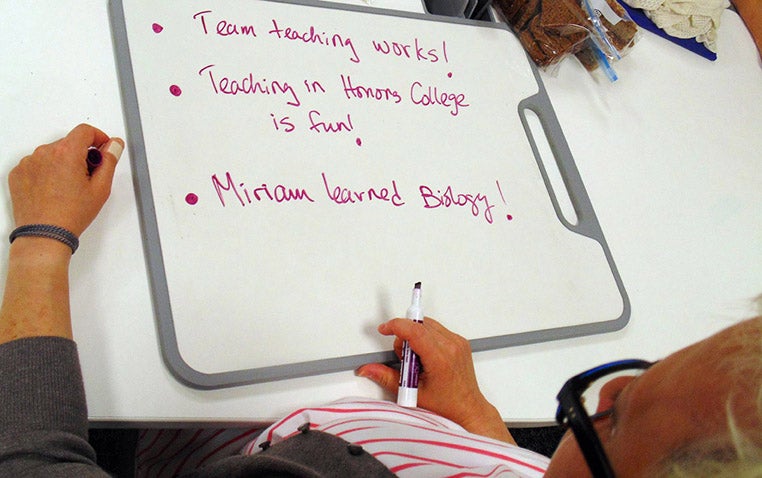

Other faculty members with Eisen, who directs the UO's Science Literacy Program (SLP), and Bright, an instructor in the comparative literature and English departments, were biologist Elly Vandegrift, SLP associate director, biologist Karen Guillemin, director of the Microbial Ecology and Theory of Animals Center for Systems Biology, and Miriam Deutsch, a professor of physics and member of the Oregon Center for Optics.

Vandegrift noted that she was able to teach concepts of protein synthesis and function by discussing gluten as a protein. "We had an opportunity to talk about how and where gluten is made, what it is, how it impacts bread and why extra gluten is added to so many different bread products," she said. "The same was true when I helped the students work through the wheat life cycle -- thinking about basic plant pollination and fertilization and farming practices by putting it in the context of one model organism."

Guillemin says the course was fun. "I brought my expertise in microbiology, immunology and biology of the digestive tract," she said. "I was fascinated to learn more about the complex microbial communities that accumulate in a bread starter and ferment the grains to produce the products which leaven the bread and infuse it with flavors. I had not suspected that these processes would be so similar to the microbial communities of animal digestive tracks that I study in my lab, but the same themes -- microbial competition for resources and transformation of the environment -- apply to both."

The course, Bright said, required a lot of preparation time, "but it was tremendously rewarding."

"As a literature and food studies scholar, I've been teaching food rhetoric from a historical perspective for years, but this course enabled me to address the political context for the science of industrialized bread in more depth than I could have had I not been teaching with the science team."

That team-teaching approach allowed the group to explore claims about bread that demand an ability to understand basic genetics and microbiology. It also let participants evaluate ideological assumptions about health and morality that guide corporate marketing and eating choices at home, Bright added.

"This course was such a wonderful experience, so enriching for the students and teachers alike," she said. "I hope the university integrates sustainable ways to allow us to teach these kinds of courses in the future, because I really believe it's a way forward in higher education."

The course officially ended with students going from table to table to taste the various breads, topped with homemade toppings, including butter and jam.

- by Jim Barlow, Public Affairs Communications