Editor’s note: This article is republished as it appears in The Conversation, an independent news publisher that works with academics worldwide to disseminate research-based articles and commentary. The University of Oregon partners with The Conversation to bring the expertise and views of its faculty members to a wide audience. For more information, see the note following this story.

Do you ever blend up a protein smoothie for breakfast, or grab a protein bar following an afternoon workout? If so, you are likely among the millions of people in search of more protein-rich diets.

Protein-enriched products are ubiquitous, and these days it seems protein can be infused into anything, even water. But the problem, as Kristi Wempen, a nutritionist at Mayo Clinic, points out, is that “contrary to all the hype that everyone needs more protein, most Americans get twice as much as they need.”

Many of us living in the most economically developed countries are buying into a myth of protein deficiency created and perpetuated by food companies and a wide array of self-identified health experts. Global retail sales of protein supplement products — usually containing a combination of whey, casein or plant-based proteins such as peas, soy or brown rice — reached a staggering $18.9 billion in 2020, with the U.S. making up around half of the market.

I am a food historian and recently spent a month at the Library of Congress trying to answer the question of why we have historically been, and remain, so focused on dietary protein. I wanted to explore the ethical, social and cultural implications of this multibillion-dollar industry.

Experts weigh in

Weight-loss surgeon Garth Davis writes in his book “Proteinaholic” that “‘eat more protein’ may be the worst advice ‘experts’ give to the public.” Davis contends that most physicians in the U.S. have never actually examined a patient with protein deficiency because simply by eating an adequate number of daily calories we are also most likely getting enough protein.

In fact, Americans currently consume almost two times the National Academy of Medicine’s recommended daily intake of protein: 56 grams for men and 46 grams for women — the equivalent of two eggs, a half-cup of nuts, and 3 ounces of meat — although optimal protein intake may vary depending on age and activity level.

For example, if you’re a dedicated athlete you might need to consume higher quantities of protein. Generally, though, a 140-pound person should not exceed 120 grams of protein per day, particularly because a high-protein diet can strain kidney and liver function and increase risks of developing heart disease and cancer.

Walter Willett, chairman of the department of nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, describes high protein intake as “one of the fundamental processes that increase the risk of cancer.” Beyond these concerns, processed supplements and protein bars are often packed with calories and may contain more sugar than a candy bar.

As stated in The New York Times, however, “the protein supplement market is booming among the young and healthy,” those who arguably need it least. The retail sales of protein products in the United States were at $9 billion in 2020, up from about $6.6 billion in 2015.

Fats and carbohydrates have, along with sugar, taken turns being vilified since the identification of macronutrients (fats, proteins and carbs) over a century ago. As food writer Bee Wilson points out, protein has managed to remain the “last macronutrient left standing.”

Why has protein endured as the supposed holy grail of nutrients, with many of us wholeheartedly joining the quest to consume ever-greater quantities?

The scoop on protein products

The history of manufacturing and marketing protein-enriched products goes back almost as far as the discovery of protein itself.

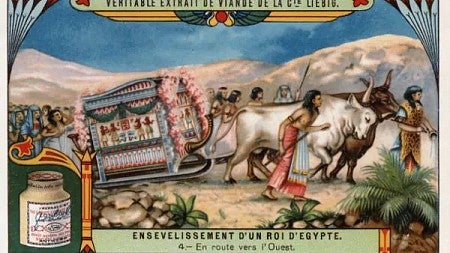

German chemist Justus von Liebig, one of the earliest to identify and study macronutrients, came to regard protein “as the only true nutrient.” Liebig was also the first to mass-produce and distribute a product associated with protein in the 1860s, “Liebig’s Extract of Meat.”

Protein consumption has remained a central component of nutritional advice and marketing campaigns ever since, even amid recycled and recurring arguments over the optimal amount of protein and whether plant or animal sources are best.

Around the time Liebig launched his extract company, John Harvey Kellogg, a staunch vegetarian, set out to redefine traditional American meals at his health sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan.

The Kellogg family invented flaked breakfast cereals, granola, nut butters and various “nut meats,” which they produced, packaged, marketed and sold across the nation. Kellogg wrote countless tracts denouncing meat-heavy diets and assuring readers that high-protein plant foods could easily replace meat.

In an April 1910 issue of his periodical “Good Health,” Kellogg posited that “Beans, peas, lentils and nuts afford an ample proportion of the protein elements which are essential for blood making and tissue building.”

How protein regained its status

Alongside the meat and cereal companies consistently touting the high protein content of their foods, the first processed protein shake appeared on the market in 1952 with bodybuilder mogul Bob Hoffman’s Hi-Proteen Shakes, made from a combination of soy protein, whey and flavorings.

In the 1970s through the 1990s, protein products remained visible but receded somewhat with the dietary spotlight firmly fixed on low-calorie, low-fat, sugar-free snack foods and beverages following the publication of studies linking sugar and saturated fat consumption to heart disease. These decades gave us Slimfast and Diet Coke as well as fat-free (and guilt-free) SnackWell’s cookies and Lay’s potato chips.

New research in 2003, however, suggested high-protein diets could aid in weight loss, and protein quickly regained its former nutrient superstar status.

Entire diets followed, each offering an array of protein drinks and bars. Robert Atkins first published his low-carb, high-protein “Dr. Atkins’ Diet Revolution” in 1982. It went on to become one of the 50 best-selling books of all time by the early 2000s, despite a New England Journal of Medicine article in 2003 clearly recommending that “Longer and larger studies (were) required to determine the long-term safety and efficacy of low-carbohydrate, high-protein, high-fat diets” such as Atkins.

The long-term pursuit of protein in hopes of achieving bigger muscles, smaller waists and fewer hunger pangs shows no sign of abating, and there has never been a dearth of those willing to take advantage of the public’s dietary goals by handing out unnecessary advice or a new protein-packed product.

In the end, most people living in high-income nations are consuming enough protein. When we replace meals with a protein bar or shake, we also risk missing out on the rich sources of antioxidants, vitamins and many other benefits of real food.![]()

—By Hannah Cutting-Jones, Department of History