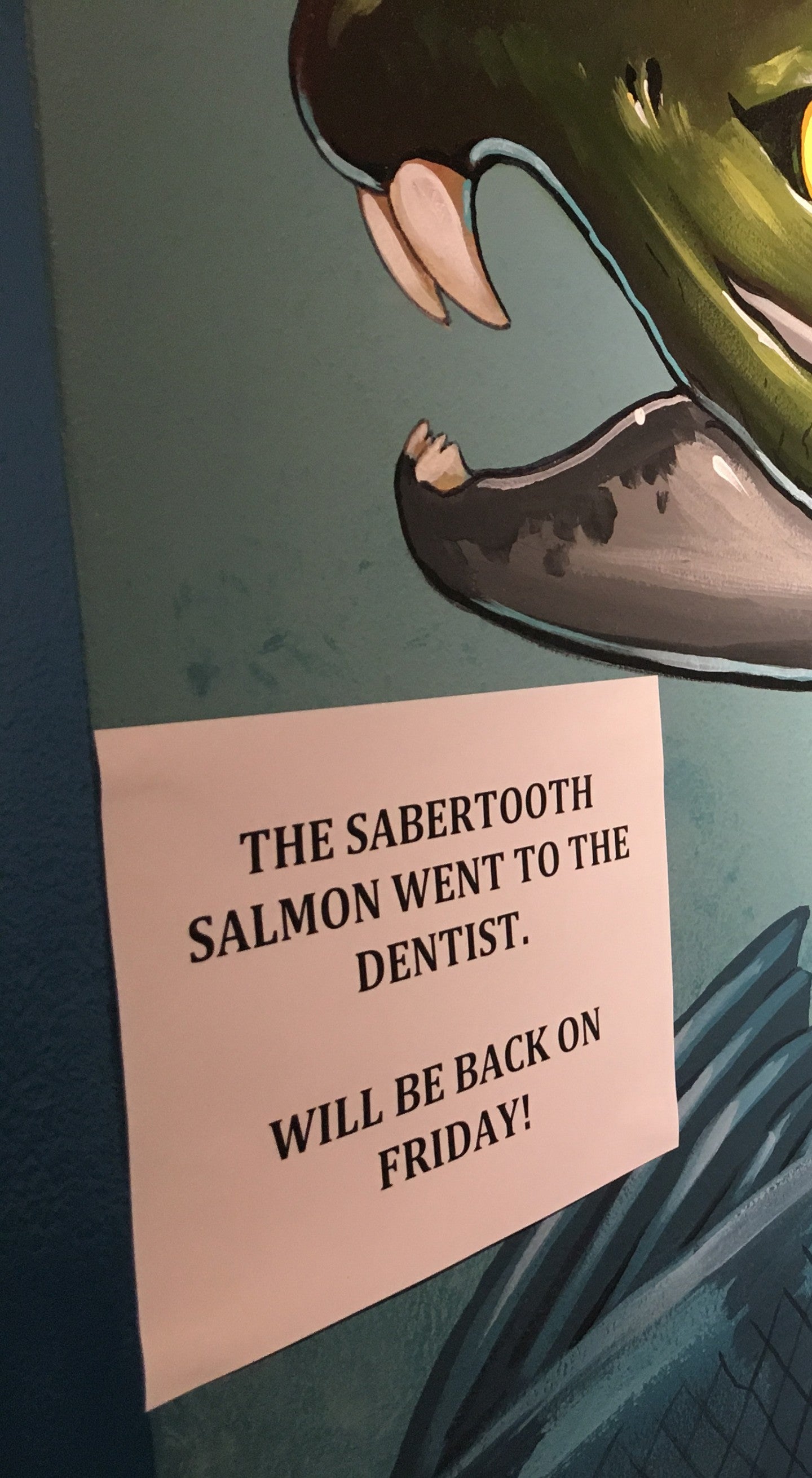

The Museum of Natural and Cultural History’s iconic sabertooth salmon sculpture recently underwent a major dental procedure.

Earlier this month artist Gary Staab, the creator of the six-foot-long replica, spent a day modifying it in response to changing scientific insights. And that required a little cosmetic dentistry to get its fearsome fangs pointing the right direction.

The giant fish species, a relative of modern sockeye salmon, swam in Oregon waters until around 4 million years ago and was long thought to have had pronounced, canine-like teeth that pointed downward from its upper jaw. That understanding was based on a fossil skull uncovered in 1964 at a quarry near Madras.

“These new fossils turned our understanding sideways — literally,” Davis said. "They are the first to be found with the saber teeth intact in the skulls, and in both of them, the teeth are actually pointing sideways out of the jaw.”

Davis said the fossils, which were painstakingly freed from the surrounding rock material by museum volunteer Pat Ward, indicate that the sideways positioning isn’t an anomaly.

“This isn’t one unusual individual,” he said, “We have two skulls presenting the same pattern.”

The pattern also appears on a specimen that recently surfaced on eBay after decades in private possession. Collected from the Madras quarry during the 1980s, the specimen includes a complete skull as well as multiple vertebrae.

Earlier this year, Oregon fossil collector Gregory Carr led an effort by the North America Research Group, a society of amateur paleontology enthusiasts, to purchase the specimen. The group has donated the assemblage to the Museum of Natural and Cultural History; it will be housed at the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry until the UO museum can prepare a space for it.

In Eugene to install and unveil the museum’s new, life-size Columbian mammoth sculptures, Staab devoted part of his visit to the tooth adjustment. With the help of the museum’s exhibitions team, he carefully dismounted the giant salmon and transported it to a studio space on campus. There he sawed off the so-called saber teeth and reattached them in the sideways position.

“The procedure went swimmingly, and the updated sculpture is now back on public view,” said Lyle Murphy, exhibitions developer at the museum.

Staab is known for blending science and art to bring extinct species back to life. His works have appeared at museums around the country, including the Smithsonian Institution, Houston Museum of Natural Sciences, Denver Museum of Nature and Science, and the Indianapolis Children’s Museum.

This wasn’t the first time Staab has modified one of his works to align with new evidence.

“The picture can change as a result of ongoing research. That’s the nature of science,” he said. “Paleoartists can’t be afraid of being wrong.”

—By Kristin Strommer, Museum of Natural and Cultural History